jimber-Derived Revenues: Importance to Local Governments in Oregon FOREIT REIEAPCH LAB

advertisement

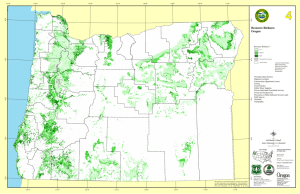

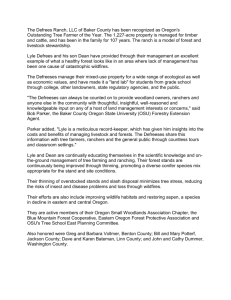

AJIJfl47141tI Special Publication 17 October 1988 OREGON / Li jimber-Derived Revenues: Importance to Local Governments in Oregon (fiscal years 1982-83 through 1986-87) Kevin Hackworth Brian Greber FOREIT REIEAPCH LAB College of Forestry Oregon State University The Forest Research Laboratory of Oregon State University was established by the Oregon Legislature to conduct research leading to expanded forest yields, Increased use of forest products, and accelerated economic development of the State. Its scientists conduct this research In laboratories and forests administered by the University and cooperating agencies and Industries throughout Oregon. Research results are made available to potential users through the University's educational programs and through Laboratory publications such as this, which are directed as appropriate to forest landowners and managers, manufacturers and users of forest products, leaders of government and Industry, the scientific community, and the general public. The Authors Kevin Hackworth, formerly Graduate Research Assistant, Department of Forest Management, Oregon State University, Corvallis, is now Management Forester, International Paper Company, Gardiner, OR. Brian Greber, formerly Assistant Professor of Forest Economics, Department of Forest Management, Oregon State University, Corvallis, is now associated with Clear Pine Molding, Prineville, OR Legal Notice The Forest Research Laboratory at Oregon State University (OSU) prepared this publication. Neither OSU nor any person acting on behalf of such: (a) makes any warranty or representation, express or Implied, with respect to the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the Information contained in this report; (b) claims that the use of any information or method disclosed In this report does not infringe privately owned rights; or (c) assumes any liabilities with respect to the use of, or for damages resulting from the use of, any Information, chemical, apparatus, or method disclosed In this report. Disclaimer The mention of trade names or commercial products In this publication does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. Acknowledgments We wish to thank Kenneth Tollenaar, Bureau of Governmental Research, University of Oregon, and Frederick Kites, State of Oregon Department of Revenue, for their special assistance. To Order Copies Copies of this and other Forest Research Laboratory publications are available from: Forestry Business Office College of Forestry Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon 97331 Please include author(s), title, and publication number if known. Timber-Derived Revenues: Importance to Local Governments in Oregon (fiscal years 1982-83 through 1986-87) Kevin Hackworth Brian Greber Contents 1 Introduction 1 Background 1 Objectives 2 Forestry-Related Revenue Sources 2 Revenues from the Public Sector 2 National Forests 2 Land Administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) 2 Oregon and California (O&C) Railroad Land 2 Coos Bay Wagon Roads 3 Payments in Lieu of Taxes 3 Public Domain Land State Forests County Forests 3 Revenues from the Private Sector 4 Severance Taxes 4 Real and Personal Property Taxes 4 Other Revenue Sources 3 3 4 Forest Fee and Yield Tax 4 Western Oregon Small-Tract Option 4 Forest Products Harvest Tax 5 Contributions of Timber-Derived Revenues to Local Governments (Fiscal Years 1982-83 through 1985-86) 5 County Governments 6 Payments from the Public Sector 6 National Forest Revenue Sharing 6 Bureau of Land Management 7 State Forests 7 County Forests 7 Severance Taxes 7 School Districts 7 Payments from the Public Sector National Forest Revenue Sharing 8 State Forests 7 8 Severance Taxes 9 Education Service Districts 9 Rural Fire Protection Districts 9 Road Districts 9 Contributions of Forestry-Related Firms to County Property Tax Receipts (Fiscal 1986-87) 10 Sources and Treatment of Data 10 Contributions to Property Taxes 11 Discussion and Conclusions 13 Literature Cited 11 14 Appendix A. Formulas for Distribution of Severance Taxes 15 Appendix B. Summary Tables of Revenues from Forestry-Related Sources 15 Table B-i. Timber-derived revenues of county governments (average, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86). 16 Table B-2. Percent of county government revenues derived from timber-related sources (average, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86). 17 Table B-3. Timber-derived revenues of school districts (average, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86). 18 Table B-4. Percent of school district revenues derived from timber-related sources (average, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86). 18 Table B-5. Timber-derived revenues of education service districts (ESD's) (average, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86). 19 Table B-6. Timber-derived revenues of rural fire protection districts (RFPD's) (average, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86). 19 Table B-7. Timber-derived revenues of road districts (average, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86). 20 Table B-8. Summary of timber-derived property taxes by county (fiscal 1986-87). 111 Introduction Background Local governments In Oregon traditionally have depended heavily on revenues from forestryrelated activities on both private and public lands (Gustaphson 1976). [For the purposes of this study, local government is defined as any form of government hierarchically smaller than the state government and receiving at least part of Its funding from property taxes (i.e., tax districts). Cities. county governments, school districts, and special districts are examples of local governments. Much of the revenue of local governments is tied directly to timber harvest levels within the state, especially harvests on national forest lands (administered by I the U.S. Forest Service) and Department of the Interior lands (administered by the Bureau of Land Management [BLMI). Several programs have been set up to compensate local governments equitably for property taxes foregone on government-owned lands. The private sector also makes significant payments to local governments, primarily as real and personal-property taxes on forest land and related capital, and severance and forest-products taxes on timber harvests. These taxes come from both industrial and nonindustrial forestry-related sources, but most come from Industry. Harvest levels varied widely from 1965 to 1985, with a general downward trend in harvest volume (FIgure 1). Beuter eta! (1976) and Stere et aL (1980) projected further declines In timber harvests on both federal and private lands, and indeed, recent Forest Service announcements have proposed significant reduction In harvest levels on national forests in Oregon. These forecasts have raised certain concerns within local governments about potential budgetaiy problems from reduced harvest-related payments. Reduced harvest from federal land could put pressures on local government budgets by reducing revenues, both from private taxes and from public revenue sharing and payments In lieu of taxes. Such services of local governments as county road maintenance, county-based law enforcement, and school programs could be reduced as a result. Alternatively, reduced harvest could lead to higher tax rates on private property. Objectives Since private harvest levels have declined steadily and harvests on national forests probably will decline in the near future, a more specific understanding of how harvest reductions will af- fect revenues of Oregon local governments Is needed. This study has two primary objectives: (1) to extend the concept that government payments connected to forestry-related activities contribute an important part of county government revenue to include other local governments and other forestry-derived revenues; (2) to differen- tiate between impact of reduced harvests on county governments and those on other local governments (specifically school districts, education service districts, rural fire protection districts, and road districts). Previous county revenue studies have dealt with the fiscal impacts on county governments of Oregon's timber industry and public land holdings. Some have interpreted these studies as pertaining to all local government revenues. This study will refer to the county as a whole (all local governments within a county's borders) as the "county," to the organization responsible for county services as the "county government," and to other local governments (e.g., school districts) by TOTAL 2 DTOTALPRIVATE OTOTALI-1ARVEST 0 IuI;IuuIIulIuIuIuup 965 1969 1973 1977 1981 1985 FIgure 1. Harvest levels on federal and private lands (1965-85). Source: State of Oregon Department of Forestiy, Annual Harvest Reports. type. To address our objectives, we have divided the study into three parts: (1) a general description of sources of forestry-related revenues; (2) analysis of the average dependence of local governments on severance tax offsets and nonlevied timber revenues in fiscal 1982-83 through 1985-86; (3) analysis of the contribution made by forestry-related finns to county property taxes in fiscal 1986-87. (The latter two parts could not be combined because of inavailability of comparable data.) 1 Forestry-Related Revenue Sources Revenues from the Public Sector granted to the Oregon and California Railroad, Sources and distribution of revenues from the public sector are summarized In Table 1. commerce and trade between California and the Pacific Northwest. In 1937, these lands were were to provide capital to hasten construction of a railroad to aid in transportation and promote forfeited to the government because of their ifiegal National Forests sale by the railroad, and their management re- Oregon's 14 national forests contain over 15 million acres. In 1900, the U.S. Congress mandated that 25 percent of gross revenues derived from national forests be paid to the counties in proportion to the area of national forest lying within each county (Nicholson and Tedder 1982). The revenues that the county receives from this program are earmarked for specific purposes: 75 percent must go to the county road fund, and the remaIning 25 percent is placed In the county school fund. Schools in Grant and Coos counties can receive more than 25 percent of these payments, but tracing these additional school allocations Is difficult; this report addresses minimum possible school allocations (25 percent) in these two counties. Land Administered by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) Oregon and California (O&C) Railroad Land There are about 2.5 million acres of "O&C" verted to the General Land Office (precursor of the BLM). A revenue-sharing formula was set up stipulating that 50 percent of gross revenues generated on these lands were to be contributed to the general funds of counties with O&C lands. Coos Bay Wagon Roads In 1869, the U.S. Congress granted the State of Oregon land to build a military wagon road between Coos Bay and Roseburg,1 under the same conditions as O&C railroad land grants. Illegal sales again led to reversion of the lands to the federal government. In 1939, a program was set up to compensate local governments for property taxes foregone on these lands. These lands make payments to county governments on a per-acre basis rather than on the basis of the property tax value of the land In a given year. This implies that the payments are not truly In lieu of taxes, but rather an annuity from the BLM to the county land in Oregon, all of which are located west of the government. Harvest revenues from this land are used to compensate the two counties In which the lands are located; payments equal the taxes that Cascade Mountains. 'Act of March 3, 1869 (15 Stat. 340) These lands, originally Table 1. Summary of sources and distributions of timber-derived revenues from the public sector. Agency/source U.S. Forest Service Bureau of Land Management Oregon and California Railroad lands Coos Bay Wagon Road lands Payments in lieu of taxes Public domain lands State of Oregon Retained land grants Former county lands County County forests 2 Revenue formula Distribution 25% of gross receipts 75% to county road fund 25% to county school fund 50% of gross harvest receipts Property tax value of land Per-acre payment 4% of net receipts, apportioned on basis of county area County general fund Taxing units within the county Taxing units within the county Public roads and bridges Interest earnings on invested harvest revenues All harvest receipts Common school fund All harvest receipts County general fund 10.0% for management 67.5% to county tax districts 22.5% to county school fund would have been paid if the land were privately owned. Revenues are divided among the taxing units within which the Coos Bay Wagon Road lands are located, based on each unit's proportion of the combined tax rate for the current year. Payments in Lieu of Taxes In 1976, a federal statut& created a new federal payment system, Payments in Lieu of Taxes." The payments are not, however, truly in lieu of taxes, in that they are based on a per-acre payment, not on foregone private property taxes based on assessed values. Payments in lieu of taxes generally apply to government lands that do not fall under other special tax provisions. State Forests The State of Oregon administers about 786,000 acres of forest land. These lands originated from two separate sources. Some are from retained land grants from the federal government; revenues from this land go to a common school fund. Most of the state forest land Is from former county land; revenues from these lands are used for management of the lands, county tax districts, and county school funds. County Forests A few counties own and manage county forests. Revenues from this land go to the general fund of the county that owns the land. Public Domain Land Public domain lands are former homestead Revenues from the Private Sector lands in Oregon that are now under BLM manage- ment. Receipts from these lands include Umber, land, and material sales. Four percent of the net receipts from these sources is paid to Oregon counties; shares are based on the area of each county. These funds are earmarked for construction and maintenance of public roads and bridges. Some of the money derived from this land is from forestry sources, but the exact amount was not available and therefore could not be included in this analysis. Sources and distribution of revenues from the private sector are summarized in Table 2. Timber revenues from the private sector are primarily from taxation of capital equipment, privately owned timber and the land upon which it grows, and land owned by forestry-related firms that Is classified as industrial on the county tax rolls. Under current law, privately owned land and 2 Act of October 20, 1976 (90 Stat. 2662, PL94-565) timber may be treated under one of several tax systems, depending on size and geographic location of the resource. Table 2. Summary of sources and distributions of timber-derived revenues from the private sector. Source Timber System Tax formula Use of revenue Western Oregon Severance Tax (WOST) 6.5% of harvest receipts' Property tax offset Eastern Oregon Severance Tax (EOST) 5.0% of harvest receipts' Property tax offset Forest fee and yield tax Current 'phase-out" rate Property tax offset Forest products harvest tax Cents per 1000 bd. Forest Practices Act ft.2 Forest research Fire control Real and personal property Local property tax treatment Value x tax rate Regular tax revenue Timber and land Western Oregon Small Tract Option Productivity value x tax rate Regular tax revenue 2 See Appendix A for detailed formula. Rates and apportionment are set every two years. Severance Taxes Under this system, timber and land are Other Revenue Sources tax system at a special reduced assessed value. Severance taxes are used as a property tax offset The revenue from the following sources was not obtainable and therefore was not included in the analysis. Their descriptions are included to give a more complete picture of the full range of private timber-related sources of revenue. The contributions to the total revenues of local governments from these programs are relatively small and should therefore not affect the findings to any significant degree. for local property tax levies. The offset payments serve effectively as a private property tax payment Forest Fee and Yield Tax treated as separate entities. Timber is taxed at 6.5 percent of gross harvest receipts at the time of harvest under the Western Oregon Severance Tax (WOST) system and 5 percent under the Eastern Oregon Severance Tax (EOST) system. Land is taxed as real property under the normal property and are treated as such in our description of Importance to local governments. The Timber Section of the State Department of Revenue determines how much a county in Areas designated as "reforestation lands" are stifi treated under the old ad valorem tax system. These lands are now being phased into the severance tax system. The rate at which harvests from western Oregon will receive from the WOST program. The county then uses a district distribution formula to offset the levies of its tax districts. The these lands are taxed depends on the current formulas used to calculate these payments (Appendix A) are based on 5-year harvest values and forest land values in the county. Even If no timber Western Oregon Small Tract Option is harvested in a county in a given year, the county could stifi receive a WOST payment. if timber had been harvested In at least one of the previous four years. This reduces fluctuation In payments over time. 'phase out" rate. If a tract of timber in western Oregon is 10 to 2,000 acres, the owner may have his forest property treated under the Western Oregon Small Tract Option, rather than under the WOST system. This tax is part of the local property tax system, with both land and timber taxed on the basis of an assigned productivity value of the land. The De- The EOST program distributes payments to counties by a much simpler formula (Appendix A) based solely on 1964 appraised timber values. Each county receives a share of net collections based on its proportion of the total appraised value of timber in eastern Oregon in 1964. The county assessor allocates the amount of revenue certified by the county treasurer to the districts. A paper detailing these payment systems is available from the State of Oregon Legislative Revenue Office partment of Forestry determines the value at which the property will be taxed; productivity (1986b). gon. Real and Personal Property Taxes Forest Products Harvest Tax Forest industries are capital-intensive and hold a relatively high proportion of the total assessed value of real and personal property in many of the smaller forested counties. Many local governments rely on taxes on real (plant, equipment, and land) and personal (nonfixed capital) property of forest industries to provide a significant part of The Forest Products Harvest Tax is collected at the time of harvest on both public and private land. It is not shared with local governments. The revenues are dedicated for specific purposes: implementation of the Forest Practices Act, forest research, and emergency fire control. The tax was 46 cents per thousand board feet in their budgets. fiscal 1986-87. 4 values varied from $3 to $229 per acre in 1986. The State of Oregon Legislative Revenue Office (1 986a) reported that only 186,219 acres were classified under the Small Tract Optional Tax in 1986. Estimated property tax payments for the 1985-86 fIscal year amounted to only about $300,000 statewide. Downing et aL (1976) have examined the significance of small woodland ownership in Ore- Contributions of Timber-Derived Revenues to Local Governments (Fiscal Years 1982-83 through 1985-86) Many of the county government revenue data were obtained from the Oregon County Finances (1983- 1985) publicatIons of the Bureau of Government Research and Service at the University of Oregon. Figures for school district revenues were taken CL1OLBIA TILLAMOOK WALLOWA SHERMAN PU______ MORROW CLACKAMAS YAMHILL from the State of Oregon, Depart- U U ATIL LA HOOD WASHINGTON UNION GILLIAM ________ WASCO ment of Education publication, BAKER Audited Resources of Oregon School Districts and ESDs (1983-84 to 1985-86). Summary of County Governments County governments provide many services. They maintain county-owned roads,3 administer property tax collections and levy submissions, provide law-enforce- LN JEFFERSO,..r:E GRANT DESCHUTES 0)0 MALHEUR I DOUGLAS CURRY JACKSON HARNEY KLAMATHh LAKE JOSEPHINE ment services, administer extension programs, and provide public and mental health services and human and community organization services. County governments also act as intermediary In distribution of revenues from various revenue programs I'll' ''I'll''''' to tax districts in the county. Individual county governments vaiy in their dependence on timber- related revenues for maintaining these services, but all depend on them at least to some degree (Figure 2; Appendix B, Tables B-i and B-2). Typically, the amount of money a county receives from timber-related sources depends on how much of the resource lies within that county's borders and the value of the timber harvested. In general, counties with little or no forest land relative to their total area (e.g.. Gilliam, Morrow, and Sherman Counties) receive most of their revenues from non-timber-related sources. Counties having pro- PERCENT OF TOTAL CALCULATED REVENUE D <1% 20-29% o 1-4% 30-39% 0 10-19% >50% o These should not be confused with road Figure 2. Percent of total county government revenue derived from districts. Road districts operate on separate Umber-related sources (average, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86; budgets and submit lridMdual property-tax see Appendix B, Tables B-i and B-2, for detailed figures). levies, 5 portionately more timberlands (e.g., Douglas, Curry, Grant, and Tillamook) depend greatly in most cases on revenues received from timberrelated sources. Of Oregon's 36 county governments. 25 depended on timber-related revenues for at least 10 percent of their budget; 17 counties depended on these payments for at least 20 per- cent of their total revenue, and 9 counties depended on this source of revenue for 40 to 50 percent of their revenue (Figure 2, Table B-2). Statewide, county governments depended on timber-related payments for roughly 17 percent of their total revenues (Table B-2). County governments relied on national forest revenue sharing for about 8.4 percent of total revenues. This program provided the most revenue of all programs, but use of this revenue Is restricted. It therefore may not be as valuable to the operation of the county governments as O&C revenues, which are placed in the county general fund. Other programs are much less significant statewide: none accounted for more than 0.6 percent of total revenue, and combined they accounted for less than 2 percent. Payments from the Public Sector National Forest Revenue Sharing National forest revenue-sharing payments were the most important timber-related revenues for county governments (Tables B-i, B-2). Grant and Lake Counties depended on these payments for nearly 50 percent of their total revenue, on the average, between fiscal 1982-83 and 1985-86. Thirteen other county governments depended on national forest payments for at least 15 percent of their revenues. The heavy reliance of some counties on revenue-sharing payments is of great significance when considering effects of reduced harvest values from national forests. Those counties that have depended on national forest pay- ments for at least 25 percent of their revenue (Crook, Grant, Harney, Klamath, Lake, and Wheeler) probably would be impacted the most by harvest reduction. Since 75 percent of these payments are earmarked for the county road fund, upkeep and construction of county roads would probably be affected first by a substantial reduction In harvest value. 11 funding for county roads was kept at prereduction levels, other county serv- ices would have to be reduced or county taxes would have to be increased. Bureau of Land Management O&C Payments Currently, payments from harvests on O&C lands provide a large part of the financing for county governments (Tables B-i, B-2). The O&C payments also can be distributed by the county government to school districts within the county. To determine howmuch of the O&C payments was used for school districts and how much was available for county government use, we subtracted payments earmarked for schools from state trust lands and national forest revenue-sharing from the county government's total payments to school districts. The remainder was then deducted from total O&C payments. Realistically, the amount subtracted from O&C revenue Is overstated. These calculations were performed to demonstrate the Importance of the O&C revenue to county governments even If the county government payments to schools were taken from O&C funds. They represent a minimum payment from the viewpoint of the county government's ability to utilize O&C payments for its own expenses. Of the 18 county governments receiving payments from O&C lands, 7 received 12 percent of their total revenue from O&C payments (Tables B-i, B-2). Douglas County averaged about $11.7 millIonabout 30 percent of total revenuesover the period. Jackson County averaged over $8 million and Lane County over $7 million from O&C payments. about 36 and 12 percent of total revenue, respectively. Josephine County government received about 42 percent of its revenue from this source. The precise impact of changes in these revenues is difficult to discern, since they go into the county general fund and can be used as seen fit by the county government. It is likely, however, that reduced O&C payments would lead to either a decline in services paid for out of county general funds, an increase In property taxes, or both. Coos Bay Wagon Road Only Coos and Douglas counties receive this payment. Payments to the county government itself are not very substantial, since most of these revenues are passed through to schools and other taxing districts. Payments in Lieu of Taxes BLM payments in lieu of taxes accounted for less than 1 percent of total net revenue for the majority of county governments (Tables B-i, B-2). Five counties, however, depended on these payments for at least 3 percent of total net revenue, Of these, Maiheur, Lake, and Harney Counties received, on average, about 5.2 percent, 6.4 percent, and 8.9 percent of total net revenue, respectively, from this program. This Is not surprising, since these counties have rather small populations and contain the largest acreages of BLM land under this program. Sh'1 D A ' School districts may obtain money directly from several timber-related sources: national forest revenue-sharing, state forest lands, and severance taxes (Figure 3; Tables B-3, B-4). School districts may also receive funds, Including reve- nues from O&C timberlands, from the county general fund. For this study, the finances of all school State Forests Most of the revenue acquired from state forest lands Is channeled to other local governments and does not generally affect the operation of county governments. State forest revenues were therefore excluded from total revenue for all but Clatsop County, which apparently relies to a substantial degree upon revenues from former county land. if state forest revenues are removed from the Clatsop County county government budget, a deficit results. Payments that Clatsop County made to other local governments from this source could not be determined; hence, the percent of the total revenue of the county government is somewhat overstated. The minimum possible payment to districts within each county were assembled into a county-wide summaly. The relative Importance of timber revenues was expressed as a proportion of revenue newly acquired by schools during the fiscal year. Newly acquired revenues were used for simplicity; previously acquired revenues remained fairly constant each year over the study period. Thus, the percentages expressed in Table B-4 are for the county school districts as a whole and may not describe exactly the relative importance of specific timber payments to an individual school district within the county. Although state forest contributions and O&C funds were not included In the evaluation of total timber contribution, the contribution from timber- schools was deducted, however, to provide a closer estimate of the true contribution to total revenue. related sources was still quite substantial for County Forests were used to estimate maximum payments for schools, O&C funds would contribute from 0 to Many counties own forests, but only two relied on them for substantial revenue. This revenue was especially Important to Hood River County, contributing over 1 mIllion dollars annually to the county general fund over the period and accounting for nearly 35 percent of the county's total revenues. Revenues to Coos County from county forests accounted for almost 12 percent of the total county government revenue. Since these revenues accrue to the county general fund, it is again difficult to predict the precise impact on county government expenditures and tax rates. Severance Taxes Severance taxes (EOST and WOST offset payments) did not contribute substantially to the revenues of any county governments. Tillamook, Lincoln, and Columbia counties received roughly 2 to 3 percent of their revenues through the WOST program. In most counties severance taxes accounted for less than 1 percent of total revenue. Sherman County received no severance taxes over the period. school districts In some counties. if the O&C minimum payments procedure for county governments 2.75 percent of school funds (Tables B-3, B-4). On a statewide basis, dependence of schools on severance tax and national forest payments was quite small, about 2.7 percent. Statewide averages can be misleading, however, because counties differ greatly In population and dependence on tim- ber-derived revenues. The more populated but less timber-dependent school districts have very large budgets relative to the smaller, more timber- dependent districts. Thus, saying that Oregon school districts obtained about 2.7 percent of total annual revenue from forest-related sources does not accurately describe the dependence of individual school districts, which ranged from 21 percent in Lake County to less than 1 percent in Multnomah and other counties. Payments from the Public Sector National Forest Revenue Sharing The national forest payment to schools was calculated as 25 percent of the national forest payment to each county. (Because Grant and Coos 7 Counties are allowed to disperse more than 25 percent of these payments to schools, the payments calculated for those counties should be Dependence of school districts on national forest revenue-sharing payments ranged from viewed as minimum possible payments. national forest land to about 16 percent In Lake o percent of the budget In counties with utile or no Cr11t,hT tii1 1 7 i pr)1 in C_r,rf County, which contain extensive national forest acreage (Tables B-3, B-4). Crook, Harney, Kiarnath, and CLATSOP COLUMBIA RWERMAN WAaoWA 1LLAMOOK CLACKAMAS>J4JORROWl 4UNON\ VAMLL LBR(XN URN JEFFERSON WHEELER GRANT ,._rL_ BENT / / DESCHUTES CCOS MALHEUR oijcts HARNEY f CURRY JACKSON KLAMATH State Forests Since amounts of payments from state forests were not avail- able, minimum payments were again estimated to permit some CRCOK LANE Wheeler counties received at least 5 percent of school-district revenues from this source. LAKE JOSEPHINE understanding of the Impacts that payments from this source have on school revenue. The minimum payment to schools was assumed to be 22.5 percent of revenue from state forests in each county. Clatsop and Tillamook counties depended most on these payments. which contributed about 7 and 3.5 percent of newly acquired school revenue, respectively. Severance Taxes Inmost Eastern Oregon school districts, EOST payments ac- counted for less than 1 percent of revenue. About 5.6 percent of Lake County school-district revenues were made up of EOST payments, by far the highest amount received from this program. WOST payments made up proportionately more of western Oregon school revenues than did PERCENT OF TOTAL CALCULATED REVENUE <1% [310-14% o 1-4% [3 15-19% 20-25% 0 5-9 FIgure 3. Percent of total school district revenues from timber-related sources (average, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86: see Appendix B, Tables B-3 and B-4. for detailed figures). EOST payments of eastern Oregon school revenues. The smaller, more populated counties received rela- less in WOST payments. Costs of operating these school tively districts tend to be relatively high, but greater nontlmber tax-base resources are available in the metropolitan areas in which they are lo- cated; thus severance taxes are proportionately less important. Counties with large annual private harvest levels, such as Coos and Douglas. receive proportionately more from WOST payments than do counties with smaller private harvest levels. Douglas County schools received a little more than 10 percent of their revenues from this source. Coos, Clatsop, Lincoln, and Tillamook Counties averaged at least 5 percent of annual newly acquired revenue from WOST offsets. Education Service Districts Education service districts (ESD's) provide a variety of services to school districts, such as special education services, payroll accounting, grade reports, and workshops for teachers and administrators. Most funding for the 29 ESD's in Oregon comes from federal and state grant funds. They also submit a levy and receive property tax money. In addition, ESD's receive severance taxes through EOST or WOST (Table B-5). For the purposes of this study, the Llnn-Benton ESD was split into Llnn and Benton sections so that the contribution from severance taxes was clearer; differences were caused by disparity in private timber harvests. The ESD's in Wheeler and Lake County were the only ones to receive a substantial portion of their revenues from EOST payments: total revenue from this source averaged about 13 and 7 percent, respectively. EOST payments accounted for less than 5 percent of the total revenue In each of the other eastern Oregon counties over the period. Averaged over eligible and ineligible districts, EOST payments made up less than 1 percent of total annual ESD revenue. Western Oregon ESD's depended more on severance payments, which accounted for an average of almost 6 percent of total annual revenue. Clatsop and Douglas County ESD's depended most on this source of revenue, with WOST payments making up about 15 and 14 percent of their total revenue, respectively. Curry and Polk County ESD's relied on these payments for at least 10 percent of their total annual revenue. Other ESD's showing substantial WOST payments relative to total revenue over the period were Coos (9 percent), Llnn (5 percent), and Tifiamook (7 percent). Western Oregon ESD's relied on these payments for an average of about 2 percent of total annual revenue. Rural Fire Protection Districts Rural fire protection districts (RFPD's) can receive revenue from several sources, but their primary source of funding Is property tax appropriations. Non-severance-tax offsets were extremely small in relation to the total levies of the RFPD's (Table B-6). Reliance on severance tax payments Is expressed as the ratio of these payments to the total property tax levy for all RFPD's In the county. Eastern Oregon RFPD's received very little of their property tax revenue from the EOST program. In fact, the offset amounts made up less than 1 percent of property tax payments in every case where severance tax offsets were made. The situation for western Oregon county RFPD's was much the same, although the contribution by WOST was somewhat larger. Only Columbia and Tillamook Counties showed any substantial contribution from WOST payments, with about 3 and 4.5 percent of their tax revenues from the WOST program, respectively. WOST and EOST tax offsets made up less than 1 percent of Oregon's RFPD property tax revenues statewide. Road Districts Road districts throughout the state received very little In severance tax payments relative to property tax revenues (Table B-7). Only Clatsop County, In which WOST payments made up more than 18 percent of the total property tax revenue, received any substantial payment from severance taxes for operation of road districts. Contributions of Forestry-Related Firms to County Property Tax Receipts (Fiscal 1986-87) Determining contributions of forestry-related activities to property taxes is difficult, because of land classification differences by different counties and the sheer volume of property tax accounts related to forestry. Once the contribution Is deter- mined, assessments can be made of potential effects on property tax revenues if variation in harvest levels encourages or discourages investment In forest enterprises in the area. If harvest patterns reduce investments In forestry Industry, assessed worth of forest industry property will be reduced. Reduction in cumulative property value In a county will, in turn, Increase the tax burden of every taxpayer whose property value did not declime. Sources and Treatments of Data Severance tax and total property tax Information were obtained from the 1986-87 Oregon Property Tax Statistics Supplements published by the State of Oregon Department of Revenue. Real and personal property tax accounts were identified from tax-office records for each county for the 1986-87 tax year. Forestry-related firms (Standard IndustrIal Classification 24 or 26, U.S. Goverment Printing Office, 1972) payIng 17 or more employees were identified through the Oregon Directory of Manufacturers (State of Oregon, Economic Development Office, 1985) and the county tax offices. Firms employing fewer than 17 employees tended to be Independently owned logging companies. million In Multnomah County. The property tax contribution from forestry-related sources Is substantial in most counties (Figure 4, Table B-8). Severance taxes are treated as property tax offsets by the counties receiving these funds. Property tax offsets from the WOST program In 1986-87 averaged $1,681,219 per county. The amounts paid to individual counties, however, ranged from $87,418 In Hood River County to over $7 million In Douglas County. Property tax offsets from the EOST program averaged $206,425; payments ranged from $6 lOin Malheur County to over $2.5 million In Klamath County. Even Gilliam County, which has no forest land value, received an EOST payment. Douglas County received more in severance tax payments in proportion to total county levies than any other county in the state. The more populated western and the nonlorested eastern counties relied less on severance tax payments. Severance tax payments offset at least 6 percent of the total levy In seven western Oregon Real property taxes collected from both industrial and nonindustrial forest land were cal- counties and about 5 percent or more in three culated from the forest land value and the consoli- Property tax revenues from forest land itself did not account for more than 2 percent of the total levy in any county In the state, with the exception of Wheeler County (Figure 4). Payments from this dated tax rate within the tax code areas of each county. These calculations yield the property tax contribution from forest lands on which the timber is being treated under a severance tax system; they do not include the contributions from forest lands currently designated as agricultural or recreational land or the contributions from the Western Oregon Small Tract Option tax program. Real and personal property tax data were not available for Klamath County and forest land tax data were not available for Yamhlll County. Property taxes received from forest land for some counties overlap with the real property taxes collected from forestry firms, i.e., the land taxes paid by firms have not been subtracted from the real property taxes (those counties are Identified in Table B-8). Since the payments, for the most part, are small relathre to total property taxes collected by each county, we felt that the overlap Is not great enough to distort the findings. eastern counties (Figure 4). source averaged $261,640, ranging from $0 In Sherman and Gilliam Counties to about $1.6 million in Lane County. Revenues from timber-related personal property were fairly small. Revenues from this source averaged about $150,000 and ranged from $0 in three counties to about $1 million in Lane County (Table B-8). The maximum contribution of personal property taxes to the total levy of any county was 1.7 percent. In fact, contributions from this source accounted for less than 1 percent of the total levy In all but Douglas, Harney and Wasco Counties. Personal property taxes probably would be more substantial If one could account for the many logging contractors that the data did not include. Contributions to Property Taxes Real property tax contributions, unlike those from personal property taxes, tended to make up a Total property levies averaged about $54 million dollars in the 1986-87 tax year, ranging from $957,346 In Wheeler County to over $479 ments for timber-related firms came to about 10 significant portion of total levies in a number of counties. On average, real property tax assess- $1.16 million, about 3 percent of the total levy. Assessments ranged from $0 in Gilliam, Sherman 25 > ' I 20 FOREST LAND REAL IPERSONAL OWOST 15 0 EOST FIgure 4. Property tax contribution to counties from timber-related sources, 1986-87 tax year. and Wheeler Counties to almost $12 million in Lane County. Real property tax assessments of over $4 million In Clatsop County and almost $3 million in Columbia County translated to over 14 and 11 percent, respectively, of the total levy In those counties. Real property taxes accounted for about 8 percent of the total levy In Crook and Harney Counties and at least 6 percent of total levies In Grant, Lane, Linn and Union Counties. Severance taxes, land taxes, and real and personal property taxes combined account for a very significant portion of property tax levies (Figure 4, Table B-8). The more forested counties receive a proportionately larger contribution from these sources. The average amount received from these timber-related sources was about $1.5 million, or about 7 percent of the average county's total tax levy. This varied greatly from county to county, however; timber-related contributions ranged from 0 to over 23 percent of total county tax levies. Tax revenue from timber-related sources accounted for 23.1 and 21.2 percent, respectively, of the total levies in Clatsop and Columbia Counties. These counties received, pro- portionately. the most from these sources. Douglas County, the third highest, received almost 19 percent of its levy from timber-related firms and timberlands. Ten percent or more of the total tax levies of 13 counties was met by forestry sources, and 18 counties relied on these sources for at least 6 percent of the total tax levy. Statewide taxation of private forestry-related entities was estimated to account for about 4.6 percent of all property tax levies. The estimate rises to 6 percent If Multnomah County Is removed from the analysis and to about 7 percent if Washington County is also removed. This is, however, an underestimate, since real (excluding timber land) and personal property taxes paid by private forestry-related firms in Kiamath County and property tax revenues from forest lands with timber treated under WOST In Yamhffl County were not included. Also not included were tax revenues from owners with timberlands treated under the Western Oregon Small Tract Option, and real or personal taxes assessed to small, privately owned, forestry-related firms. Discussion and Conclusions Of the local governments studied, county 5). National forest and O&C payments to counties governments and school districts depended most on timber-related revenues. Such revenues provided from 0.1 to 37.8 percent of combined county government and school-district revenues (Figure were the most Important timber payments to county governments and schools. The impact of reducing national forest harvests could extend beyond reduction of school revenue and road 11 maintenance and construction, if a county has to redirect funding from other sources to maintain those programs. The Importance of O&C revenue cannot be assessed so easily, since the money goes Into the county general fund and, forthe most part, can be disbursed to other local governments within the county or retained by the county government for its own uses. Thus, O&C money may be an Important source of funding for a program in one county but may be used totally differently In another. The Important consideration is not necessarily how the money is used, but where program funding would come from If O&C money were not available. Severance taxes made up very little of the total revenue of the local governments examined, except In certain school districts. Severance taxes from the EOST program made up very little of total school district revenues in all eastern Oregon counties but Lake County. WOST payments to western Oregon school districts, on the other hand, made up over 5 percent of the total annual revenues received for five school districts In western counties. Timber-related firms bore a very significant portion of the property tax burden in many coun- ties during the 1986-87 tax year. Western and highly forested counties with higher timber-related industrial bases tended to assess a higher proportion of their levy against timber-related firms and to rely on property tax payments from these firms for a substantial contribution to opera- tion of local governments. If It were not for these finns, financial support of local governments probably would have to be spread out across property-tax payers through higher tax rates. The primary contributors from private finns were by far the large corporations. Payments by smaller finns were dwarfed by the enormous amount of taxes paid by the two largest contributing companies, each of which paid more than all other finns combined in their respective counties. When estimating the impact of changes in harvest levels on local governments, one should keep in mind that harvest value, not volume, ultimately determines the payments from these lands. Although closely related, they are not the same. For example, national forest harvest volumes might be reduced but harvest values maintained If stumpage prices increased enough to compensate for the reduced volume. Thus, although payments to counties and schools probably would decline given a substantial reduction in harvest levels on national forests or O&C lands, the amount of that reduction can only be assessed after the market has adjusted to reduced stumpage supply. Answers to questions such as, "How much would harvest levels have to be reduced before significant impacts would be felt by the counties?" are difficult and would depend on the county arid the ability of the county governments to find alternative sources of revenue. This analysis does not fully reflect the contribution of forestry to Oregon's local governments. 40 Figure 5. Contribution of timber-related revenues to combined county government and school districtrevenues, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86. (These figures do not Include property tax payments from forestry-related firms.) 12 The local governments Included are those that receive the most timber-related revenue. City Cycling of income taxes through state and governments, community colleges, and other tax- federal governments to local governments provides further support to local governments. Since forest Ing districts were omitted from the analysis. In addition, property taxes paid by forestry-related industry and its employees pay a significant amount of income tax in the state, one cannot firms were not added to the percent-of-total tables (Tables B-2, B-4. AppendIx 2). These payments dismiss this contribution to local government finances. Difficulties In tracing the flow of income probably make up a substantial portion of the taxes, however, precludes assessment of this revenues of local governments. contribution In the current analysis. Literature Cited BEUTER, J.H., K.N. JOHNSON. and H.L. STATE OF OREGON, DEPARTMENT OF REVE- SCHEURMAN. 1976. TImber for Oregon's tomor- NUE. Fiscal 1982 to 1986. Oregon Property Tax Statistics. Fiscal years 1982-83 to 1986-87. Sa- row: an analysis of reasonably possible occurrences. Forest Research Laboratory, Oregon State University, Corvallis. Research Bulletin 19. 111 p. BUREAU OF GOVERNMENTAL RESEARCH AND SERVICE. 1983 to 1986. Oregon County Fi- nances. University of Oregon, Eugene. DOWNING. K.B., K.P. CONNAUGHTON, and W.S. HOPKINS. 1976. Urban owners of forests In western Oregon. Forest Research Laboratory, Oregon State University, Corvallis. Research Paper 26. 11 p. lem, Oregon. STATE OF OREGON, DEPARTMENT OF REVE- NUE. 1982 to 1986. Oregon Property Tax Statistics. Statistical Supplement. Fiscalyears 1982-83 to 1986-87. Salem, Oregon. STATE OF OREGON, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OFFICE. 1985. Directory of Manufacturers. Economic Development Department, Salem, Oregon. 410 p. GUSTAPHSON, RD. 1976. Regional employment impact on timber harvest changes in Oregon. M.S. thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis. 154 p. STATE OF OREGON, LEGISLATiVE REVENUE OFFICE. 1986a. Revenue from Timber in Oregon. Salem, Oregon. Research Report 6-86. 8 p. NICHOLSON, W.E. and P.L. TEDDER 1982. Joint timber-harvest scheduling by the U.S. forest service and the Bureau of Land Management: possible STATE OF OREGON, LEGISLATIVE REVENUE effects on harvest levels and county revenues in western Oregon. Forest Research Laboratory, Oregon State University, Corvallis. Research Bulletin 37. 41 p. OFFICE. 1986b. Distribution of Oregon Timber SeveranceTax Receipts. Salem, Oregon. Research Report 6-86. 8 p. TION. 1983 to 1986. Summary of Audited Resources of Oregon School Districts and ESDs. Fiscal years 1982-83 to 1985-86. Salem, Oregon. STERE, D.H., B.R HOPPS, and G. LETFMAN. 1980. 1980 Oregon timber supply assessment: projections of future available harvests. Forest Research Planning Section, Oregon State Forestry Department, Salem. 165 p. STATE OF OREGON, DEPARTMENT OF FOR- U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1972. STATE OF OREGON, DEPARTMENT OF EDUCA- ESTRY. 1965 to 1985. Annual Harvest Reports. Mimeo. Salem, Oregon. Standard Industrial Classification Manual. 649 p. 13 Appendix A. Formulas for Distribution of Severance Taxes WOST \ County harvest value (5-year avg.) County harvest distribution (75% of net) Western Oregon avg. I harvest value / County forest land value County land distribution Western Oregon forest land value k c011eCtions (25% of net collections Total county distribution = County harvest distribution + County land distribution I District harvest distribution \ Avg. harvest value ( Avg. tax of district / rate (district)J ) (Sum of avg. harvest'I' Avg. tax value in county )lrate (county)) / Land value (Avg. tax in district / \ rate I District land distribution (county sum of\ (Avg. taxi land value ) O county distribution / '(25% of county i ) \ distribution / // rate Total district distribution = District harvest distribution + District land distribution EOST County = distribution I Appraised timber value in county (1964) I net collections I Eastern Oregon appraised timber value (1964) \ District distribution 14 District-computed property tax on timber County sum of computed tax on timber I / county t,distribution) Table 8-1. Timber-derived revenues of county governments (average, fiscal years 1982-1983 through 1985-86). County Baker Benton Clackamas Clatsop Columbia Coos Crook Curry Deschutes Douglas Gilliam Grant Harney HoodRiver Jackson Jefferson Josephine Klamath Lake Lane Lincoln Linn Malheur Marion Morrow Multnomah Polk Sherman National forest paymentst $562,710 164,529 2,512,924 0 0 O&C payments and reserves Maximum Total possible Minimum payment to schools reservest $0 1,508,114 2,978,659 $0 1,250,954 502,066 $0 257,160 2,476,593 0 0 0 1,105,592 3,166,502 599,483 268,532 506,109 2,897,970 0 0 1,958,938 352,656 0 1,606,282 0 0 233,606 1,249,925 1,521,087 3,163,055 6,212,429 13,444,215 0 0 0 2,359,838 1,275,016 804,532 2,394,558 545,386 859,398 5,734,296 2,874,090 10,732,094 1,727,476 3,641,382 3,748 1,393,148 156,498 355,910 0 0 0 0 0 0 8,410,014 394,488 0 1,792,981 11,651,234 0 0 0 0 8,015,526 0 0 0 6,483,278 1,255,867 175,925 5,094 6,307,353 1,250,773 0 0 0 8,195,336 193,210 1,416,875 811,223 193,210 485,319 7,384,113 0 0 163,020 0 0 931,556 0 3,211 783,575 0 637,214 1,159,262 637,214 178,042 0 0 0 Tillamook 934,347 Umatilla 432,484 Union 506,128 Wallowa 815,821 Wasco 1,026,065 Washington 0 Wheeler 411,607 Yamhlll 256,849 Total forstate 54,864,141 0 300,549 28,169 272,380 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 338,116 223,467 0 0 114,649 0 0 386,421 53,721,734 0 620,555 0 0 981,220 111,673 274,748 8,173,516 45,548,218 Payments in lieu of taxest $108,106 1,918 48,451 299 0 County forestst $4,099 0 290,257 0 529 6,452 1,542,551 89,263 0 55,901 0 136,756 0 91,593 169,733 6,860 0 164,075 0 310,824 0 19,911 1,315,043 44,217 0 27,211 0 33,409 448,520 202,550 0 310,824 0 129,910 12 17,299 0 45,565 0 416,902 0 19,399 0 17,697 0 6,803 0 0 0 17,178 0 9,961 0 43,750 0 83,389 0 110,181 0 19,420 25 273 25,075 24,219 0 2,530 83 2,623,089 3,795,927 EOST*t WOST $9,510 $0 42,367 120,823 240,506 182,666 261,752 Total timber contribution Estimate of total revenue $684,425 $3,479,187 465,972 12,584,185 5,449,046 70,752,900 0 5,782,741k 10,645,200 0 689,304 5,898,683 0 4,942,331 13,070,693 10,484 0 1,349,671 4,275,848 0 34,302 3,217,571 6,990,351 9,587 0 3,309,398 16,549,466 0 542,834 18,667,822 39,962,874 136 0 6,996 3,355,452 18,326 0 2,542,239 4,805,248 1,734 0 1,587,574 4,838,614 0 15,440 2,154,925 3,809,509 0 39,974 10,494,275 22,534,632 10,016 0 582,612 3,309,624 0 2,377 7,651,057 15,059,280 106,959 0 7,294,578 18,438,385 80,330 0 3,265,243 5,999,484 0 393,514 18,639,642 62,394,461 0 321,694 2,066,469 11,673,542 0 422,953 5,041,456 15,844,122 86 0 420,735 4,691,568 0 58,579 2,091,680 34,905,147 22,339 0 196,534 5,397,010 0 33,668 396,381 133,191,142 0 129,514 1,113,944 7,131,948 0 0 17,178 1,382,543 0 181,381 1,398,069 6,783,691 12,644 0 488,877 8,310,388 18,370 0 607,887 4,485,565 19,446 0 945,448 5,081,434 8,586 0 1,054,096 7,203,388 0 71,269 211,265 6.4,643,425 10,445 0 446,271 1,074,289 0 78,552 612,761 8,753,005 338,997 3,174,161110,344,534 649,306,281 0 0 Source: Oregon County Finances, Bureau of Governmental Research and Service, University of Oregon (1983-86). * Source: Oregon Property Tax Statistics, Statistical Supplement, State of Oregon, Department of Revenue (1982-86). tlliJJed in calculation of total timber contribution. C1 * Clatsop County was unusually dependent on revenues from the state forests; therefore, these revenues were included in the total timber contribution for this county only. See text for details. II 0 Cl) I - II 0 Cl) Table B-2. Percent of county government revenues derived from timber-related sources (average, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86). 0) County Baker Benton Clackamas Clatsop Columbia Coos Crook Curry Deschutes Douglas Gilliam Grant Hamey HoodRiver Jackson Jefferson Josephine Klamath Lake Lane Lincoln Llnn Malheur Marion Morrow Multnomah Polk Sherman Tlllamook Umatilla Union Wallowa Wasco Washington Wheeler Yamhill StatewIde National Forest payments Minimum O&C reserves Payments in lieu of taxes County forests EOST WOST 16.17 0 3.11 0.12 0.27 0 1.31 3.55 2.04 3.50 0 0 1.79 0.02 0.07 0 8.58 22.17 0 0 0 0 0 0.34 0.17 2.26 3.10 2.00 29.23 21.76 22.98 0 0.41 0 0.01 11.80 0 0 0 0 0 19.11 0 15.55 29.16 0 0 0 49.11 26.35 21.12 10.63 16.48 5.71 31.10 47.91 17.20 14.80 22.98 0.08 3.99 2.90 0.27 0.05 0.00 13.77 5.20 11.28 16.05 14.24 0 38.31 2.93 8.45 0 0.05 2.09 0.80 0.83 0.23 0.20 3.41 0 6.42 0.52 0.20 0.82 0.22 1.10 5.18 11.83 0.21 0 0.15 0.29 8.89 0.06 0.33 0 0 35.57 0 41.88 6.78 5.88 0 1.78 0 0 13.76 0 4.02 0 0 0 0 0.18 0 3.14 7.01 0.42 0 0 0 0.25 0 0 0.49 0.00 1.36 0.06 0 0 0.38 0.04 0.21 52.91 32.81 0.30 0 56.57 46.57 17.60 2.98 0 0.02 50.81 0 0.58 1.34 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.41 0 0 0 0 0.63 2.76 2.67 39.56 54.43 29.87 17.70 31.82 8.97 5.99 3.64 0.30 15.62 1.24 0.15 0 0 0 0 0.11 0 0 0 2.17 0.27 0 0.04 0 2.25 0.03 0.40 0 0 0.58 0.97 1.24 0.15 0.53 1.86 19.67 3.70 7.70 54.32 11.69 37.81 31.56 46.03 20.00 46.71 0 0 34.52 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.01 0 0 0 0 0.41 Total timber contribution 0.41 0.38 0.12 0 0.05 0.18 0 0.17 0 0.03 1.82 0.00 2.67 0.90 0.49 20.61 5.88 13.55 18.61 14.63 0.33 41.54 7.00 16.99 Table B-3. Timber-derived revenues of school districts (average, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86). County Baker Benton Clackamas Clatsop Columbia Coos Crook Curry Deschutes Douglas GIlliam Grant Hamey HoodRiver Jackson Jefferson JosephIne Klamath Lake Lane Lincoln Linn Malheur Marion Morrow Multnomah Polk Sherman Tillamook UmatIlla Union Wallowa Wasco Washln9ton Wheeler Yamhill Total for State National forest payments EOST* WOST $0 251,127 947,714 1,248,659 1,463,273 2,648,797 $0 191,887 6,248 1,608,949 107,465 49,411 63,293 0 0 439,835 0 0 $187,570 54,843 $37,669 837,641 46,259 0 0 0 0 0 77,869 416,642 507,029 1,054,352 2,070,810 0 991,338 425,005 268,177 798,186 181,795 286,466 1,911,432 958,030 3,577,365 575,825 1,213,794 1,249 464,383 52,166 118,637 1,070 0 311,449 144,161 168,709 271,940 342,022 0 137,202 85,616 18,492,772 Estimated minimum payment from state forests 0 48,658 0 0 0 6,242,083 594 21,548 1,796 0 0 0 32,116 0 0 0 127,874 1,064,135 28,390 0 0 145,587 0 0 4,238,686 1,148,973 3,238,133 0 322,420 584,992 338,806 0 0 0 813 0 41,892 0 0 0 139,670 871,600 0 893,765 0 0 0 79,764 103,140 30,072 41,475 0 23,144 0 1,492,303 0 0 0 0 0 162 88,066 0 190,007 259,662 123,189 0 196,762 0 0 85,038 0 485,748 Total timber contribution $225,239 497,857 1,837,862 2,857,608 1,570,737 2,776,077 479,935 946,864 1,103,010 8,345,008 594 1,012,886 426,801 396,052 1,862,321 210,185 432,215 2,584,490 1,296,836 8,006,057 1,984,460 4,575,116 2,062 983,564 94,058 258,306 957,708 0 0 0 0 0 0 413,917 158,383 0 0 0 0 1,690,961 223,926 271,849 302,012 383,496 572,300 160,346 566,131 3,583,094 49,894,927 0 480,514 26,326,758 School district revenue received during year $10,097,802 39,236,165 178,382,595 22,593,238 36,525,798 42,079,986 8,313,338 9,939,906 44,642,592 61,605,943 2,133,813 5,746,098 6,612,009 11,288,424 89,827,236 10,895,151 35,121,244 34,448,306 6,072,912 174,865,011 22,550,892 66,040,184 18,854,198 142,886,746 8,279,844 438,818,935 20,456,119 2,434,953 14,178,288 41,974,753 17,763,549 5,783,278 16,188,215 180,427,860 1,787,145 39,712,259 1,868,564,781 Prior year's taxes $335,673 2,315,970 9,670,872 875,012 1,383,694 2,503,300 497,866 793,171 4,076,207 2,840,399 94,841 50,515 86,591 472,515 4,932,879 453,001 1,906,965 1,347,661 252,681 12,230,265 2,033,189 3,874,657 740,821 6,336,502 256,708 14,309,113 1,074,257 60,798 823,618 1,949,392 726,976 73,763 872,316 10,371,300 7,484 1,968,184 92,599,151 Source: Summary of Audited Resources of Oregon School Districts and ESDs, State of Oregon, Departmentof Education (1983-86). * Source: Oregon Property Tax Statistics, Statistical Supplement, State of Oregon, Department of Revenue (1982-86). Beginning balance $3,620,054 2,794,188 18,154,886 9,786,033 12,746,102 4,684,580 540,694 1,738,550 6,670,886 11,267,024 705,169 1,538,304 1,704,249 1,206,702 21,941,149 2,235,575 5,109,370 5,870,093 2,265,389 24,272,035 2,992,865 9,866,549 2,797,834 21,349,203 1,730,705 59,673,407 3,621,948 488,584 4,322,957 8,427,026 2,421,629 1,009,582 2,920,962 38,653,123 932,945 7,411,731 307,472,076 Total school resources $13,717,856 42,030,353 196,537,481 32,379,270 49,271,900 46,764,566 8,854,032 11,678,456 51,313,477 72,872,966 2,838,982 7,284,402 8,316,258 12,495,126 111,768,385 13,130,725 40,230,614 40,318,399 8,338,300 199,137,046 25,543,757 75,906,733 21,652,032 164,235,948 10,010,548 498,492,342 24,078,066 2,923,537 18,501,246 50,401,779 20,185,177 6,792,860 19,109,177 219,080,984 2,720,090 47,123,990 2,176,036,856 Q Table B-4. Percent of school district revenues derived from timber-related sources (average, fiscal years 1 982-83 through 1985-86). County Baker Benton Clackamas Clatsop Columbia Coos Crook Curry Deschutes Douglas GiHiam Grant Hamey Hood River Jackson Jefferson Josephine Klamath Lake Lane Lincoln Linn Malheur Marion Morrow Munomah Polk Sherman Tillamook Umatilla Union Wallowa Wasco Washington Wheeler Yamhill Statewide National forest revenue 1.86 0.14 0.47 0 0 0.19 5.01 5.10 2.36 3.36 0 17.25 6.43 2.38 0.89 1.67 0.82 5.55 15.78 2.05 2.55 1.84 0.01 0.33 0.63 0.03 0.01 0 2.20 0.34 0.95 4.70 2.11 0 7.68 0.22 0.99 EOST 0.37 0 0.03 0 0 0 0.76 0 0.11 0 0.03 0.38 0.03 0 0 0.26 0 1.70 5.58 0 0 0 0 0 0.51 0 0 0 0 0.19 0.58 0.52 0.26 0 1.29 0 0.08 WOST Minimum contribution from state Total timber forests contribution 0 0 0.64 0.53 5.53 0.49 4.01 6.29 0 4.42 0 10.13 0 0 0 1.13 1.18 0 0.41 0 0 2.42 5.10 4.90 0 0.23 0 0.03 4.26 0 6.30 0 7.12 0.29 0.12 0 0 0 0.05 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.26 0 0.11 1.15 0.19 0 0.14 0 0 0.42 0 3.43 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.23 0 1.21 1.41 0 0.09 0 0 0.19 2.23 1.27 1.03 12.65 4.30 6.60 5.77 9.53 2.47 13.55 0.03 17.63 6.45 3.51 2.07 1.93 1.23 7.50 21.35 4.58 8.80 6.93 0.01 0.69 1.14 0.06 4.68 0 11.93 0.53 1.53 5.22 2.37 0.32 8.97 1.43 2.67 Table B-5. Timber-derived revenues of education service districts (ESD's) (average for fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86). Total annual revenue County Baker Benton Clackamas Clatsop Columbia Coos Curry Deschutes Douglas Gilliam Grant Harney Jackson Jefferson Lake Lane Linn Malheur Marion Multnomah Polk Sherman Tillamook Umatifla Union Wallowa Wasco Washington Wheeler Yamhill Totalforstate ($) 834,909 1,903,616 9,217,945 2,375,607 1,083,272 2,768,295 920,367 603,115 3,439,039 341,062 856,061 2,308,115 8,946,702 245,713 600,703 8,162,539 3,535,286 835,161 8,114,465 24,263,595 896,468 280,192 1,847,344 4,005,523 2,170,069 2,374,192 1,152,820 4,195,061 505,790 1,896,898 100,679,919 EOST ($) 3,643 % of levy 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1,050 0 88 36,889 6,495 0 1,552 40,661 0 WOST % of levy 0.44 0 0 0 ($) 13,174 112,335 360,487 46,786 238,118 94,603 0.69 1.22 15.17 4.32 8.60 10.28 0.17 0 0 468,394 0.03 0 4.31 0 0 13.62 0 0 0 1.03 0 0.28 0 0 91,741 0 0 0.63 6.77 0 0 3.06 0 0 250,165 177,035 43 0.01 0 0 0 0 15,259 18,946 95,670 0.19 0.08 10.67 0 0 0 0 0 5.01 0 0 0 0 0 0 136,525 6,906 14,320 81,228 3,256 0.17 0.66 3.42 0.28 0 0 0 0 9,269 7.39 0 0 0 0 0.22 67,582 0 263,711 13.36 0 2,162,745 0 0 34,240 0.26 1.81 0 0 2.15 Source: Oregon Property Tax Statistics, Statistical Supplement, State of Oregon, Department of Revenue (1982-86). Revenues for Linn-Benton ESD are apportioned on the basis of the number of students within each county. Table B-6. Timber-derived revenues of rural fire protection districts (RFPD's) (average, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86). EOST % of levy Total Levy ($) ($) Baker Benton Clackamas Clatsop Columbia Coos Crook Curry Deschutes Douglas Gilliam Grant Hamey Hood River Jackson Jefferson Josephine Klamath Lake Lane Lincoln Llnn Malheur Marion Morrow Munomah Polk Sherman Tillamook Umatllla Union Wallowa Wasco Washington Wheeler Yamhill Total for state -i 40,328 932,334 11,966,635 283,682 1,976,113 626,558 79,984 172,208 1,872,149 2,479,890 36,891 27,533 11,865 240,628 3,434,665 308,413 244,263 1,739,413 74,491 2,830,102 707,805 1,626,218 194,494 3,934,976 74,225 12,200,828 520,287 9,380 336,556 541,772 128,930 8,445 402,302 15,175,017 0 507,933 65,747,310 150 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1,001 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 WOST ($) % of levy 0 3,544 40,289 2,104 67,915 0.05 5,181 0 471 0 0.38 0.34 0.74 3.44 0.83 0 0.27 0 0 2,090 0.08 26 125 0.07 0.45 0 0 0 1,916 0 212 6 0 1,155 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 374 1,088 0.16 0.03 0 0 1.20 0 0 0.98 1.15 29 505 28 0 0 0 0 5,153 0.62 0 0.01 0.01 0 0.16 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.01 0.39 0.33 0 0 0 0 0.01 2,932 0 0 27,614 8,174 Total levy County Baker Benton Clackamas Clatsop Columbia Coos Crook Curry Deschutes Douglas Gilliam Grant Hamey HoodRiver 1.21 Jackson Jefferson Josephine Klamath Lake Lane Lincoln Linn Malheur Marion Morrow Muftnomah Polk Sherman Tillamook Umatilla Union Wallowa Wasco Washington Wheeler Yamhill 0.32 Totalforstate 6,551 0 5,546 0.40 0 0 2,056 3,844 0.02 0.74 0 15,413 4.58 0 0.14 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 11,031 0 6,133 212,346 Table B-7. Timber-derived revenues of road districts (average, fiscal years 1982-83 through 1985-86). 0.07 0 Source: Oregon Property Tax Statistics, Statistical Supplement, State of Oregon, Department of Revenue (1982-86). ($) ($) 0 74,287 0 664,570 0 6,896 5,085 0 109,709 4,561 96,859 0 0 0 0 45,093 0 63,339 0 0 157,589 0 396,586 0 0 1,302 0 0 3,869 0 0 0 0 1,838 0 2,115 1,633,697 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 13 0 41 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 172 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 226 EOST % of levy 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.01 0 0.04 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.04 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.01 WOST % of levy ($) 0 0 27 0.04 0 123,751 0 22 0 0 0 12 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 567 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 124,379 0 18.62 0 0.31 0 0 0 0.26 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0.36 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 7.61 Source: Oregon Property Tax Statistics, Statistical Supplement, State of Oregon, Department of Revenue (1982-86). Table B-8. Summary of timber-derived property taxes by county (fiscal 1986-87). County Baker Benton Clackamas Clatsop Columbia Coos* Forest land tax $14,224 375,738 398,341 512,261 410,523 659,754 36,556 153,628 32,361 1,125,178 Crook Curry Deschutes Douglas Gilliam 0 Grant 43,398 Hamey 6,795 Hood River 44,049 Jackson* 271,593 Jefferson 43,190 Josephine 73,093 Klamath 321,875 Lake 99,238 Lane 1,594,734 Lincoln 664,796 Linn 813,557 Malheur 359 Marion 129,235 Morrow 18,526 Muftnomah 96,449 Polk 296,437 Sherman 0 Tillamook 304,786 Umatilla* 105,377 Union 52,180 Wallowa 53,317 Wasco 32,091 Washington* 343,270 Wheeler 30,504 Yamhill not available Total for state 9,157,413 without Multnomah Co. 9,060,964 without Muftnomah, Washington Cos. 8,717,694 Real Personal propertytax propertytax $341,860 885,014 1,344,152 4,054,599 2,972,246 1,028,941 526,164 284,001 852,498 2,303,253 $16,334 62,967 88,863 239,541 219,807 259,140 60,124 12,599 123,726 721,595 0 0 250,985 355,805 205,292 1,819,411 30,037 412,314 not available 198,843 11,773,955 1,374,695 3,794,493 8,858 1,002,773 359,340 1,746,372 220,739 29,107 45,498 28,138 372,379 17,116 89,255 not available 49,239 1,012,601 215,511 495,225 894 42,734 29,783 208,309 16,506 Total EOST Total WOST $24,224 $0 0 615,405 722,545 1,784,494 2,073,785 2,711,059 0 0 0 0 0 0 1,022,446 0 31,943,155 31,820,557 1,636,178 641,948 1,202,166 405,638 415,917 1,416,299 75,586 1,593,607 90,274,617 88,100,889 31,288,951 86,684,590 1,247,351,478 0 0 623,833 29,997 0 0 772 7,077,616 0 39,489 0 0 0 87,418 1,098,129 0 119,721 2,622,923 239,209 0 0 0 0 0 610 0 5,201,517 1,561,126 3,635,092 23,007 33,306 0 0 0 0 0 10,721 335,597 0 122,598 1,220,957 1,510,339 440,955 2,173,728 1,754,639 0 0 216,649 450,217 964,173 267,208 45,577 436,729 92,297 35,000 125,219 23,173 311,287 104,694 51,354 60,594 61,940 26,962 0 531,606 0 167,491 0 45,082 0 0 1,398,211 40,694,684 38,948,312 27,905 5,176,566 4,968,257 3,302,799 3,302,799 38,511,583 4,863,563 3,302,799 * Land taxes paid by forestry firms have not been subtracted from the real property taxes for these counties. $396,642 1,939,124 2,553,901 6,590,895 5,676,361 4,658,894 661,763 1,074,061 1,038,582 11,227,642 772 362,979 412,509 364,897 3,561,512 113,350 694,383 2,944,798 586,529 19,582,807 3,816,128 8,738,367 Total levy $8,798,352 48,450,860 191,483,714 28,494,676 26,735,113 40,234,846 6,626,667 9,498,126 48,181,077 59,503,356 2,919,498 3,499,793 4,337,517 9,463,564 74,090,322 8,049,506 28,028,766 31,832,260 5,038,415 194,660,764 34,454,540 59,843,543 16,464,537 133,406,377 12,348,172 479,226,972 28,358,002 3,120,187 16,020,620 36,611,243 13,976,720 5,484,393 18,640,135 222,652,416 957,346 37,738,471 1,949,230,866 1,470,003,894 38,919 4,411 0 0 Timber-related contribution 0 0 0 Hackworth, K. and B. Greber. 1988. TIMBER-DERIVED REVENUES: THEIR IMPORTANCE TO LOCAL GOVERNMENTS IN OREGON (FISCAL YEARS 1982-83 TO 1986-87). Forest Research Laboratory, Oregon State University, Corvallis. Special Publication 17. 20p. The forestry sector contributes significant revenues to local governments in Oregon. This paper briefly describes public and private forestry contributions and the relative Importance of these payments to five forms of local governrnentscounty governments, schools, education service districts, rural fire protection districts, and road districtsIn fIscal years 19821983 to 1985-86. The contribution of property tax payments from the forestry sector to statewide property taxes in 1986-87 Is also analyzed. Hackworth, K. and B. Greber. 1988. TIMBER-DERIVED REVENUES: THEIR IMPORTANCE TO LOCAL GOVERNMENTS IN OREGON (FISCAL YEARS 1982-83 TO 1986-87). Forest Research Laboratory, Oregon State University, Corvallis. Special PublicatIon 17. 20 p. The forestry sector contributes significant revenues to local governments In Oregon. This paper briefly describes public and private forestry contributions and the relative Importance of these payments to five forms of local governmentscounty governments, schools, education service districts, rural fire protection districts, and road districtsin fiscal years 19821983 to 1985-86. The contribution of property tax payments from the forestry sector to statewide property taxes in 1986-87 Is also analyzed. As an affirmative action institution that complies with Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Oregon State University supports equal educational and employment opportunity without regard to age, sex, race, creed, national origin, handicap, marital status, or religion. Forestry Publications Office Oregon State University Forest Research Laboratory 225 Corvallis OR 97331-5708 Oe on I Jnversity Address Correction Requested Non-Profit Org. U.S. Postage PAID Corvallis, OR 97331 Permit No. 200