Document 13872571

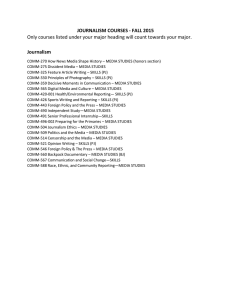

advertisement