Making education count: the effects of ethnicity and qualifications on

advertisement

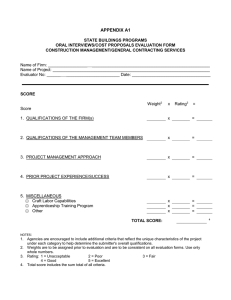

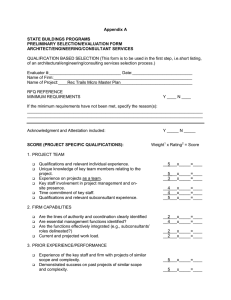

doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2007.00715.x Making education count: the effects of ethnicity and qualifications on intergenerational social class mobility Lucinda Platt Abstract This paper examines the role of social class and ethnic group background in determining individuals’ social class destinations. It explores the extent to which these background factors are mediated by educational achievement, and the role of educational qualifications in enabling intergenerational class mobility. To do this, it uses the ONS Longitudinal Study. These data allow us to observe parents’ characteristics during childhood for a group of children of different ethnic groups growing up in England and Wales in the same period and who had reached adulthood by 2001. Results show that the influence of class background on these children’s subsequent social class position varied with ethnicity: it was important for the majority, even after taking account of educational qualifications, but had a much smaller role to play for the minority groups. The minority groups made use of education to achieve upward mobility, but to greater effect for some groups than for others. Among those without educational qualifications, minority groups suffered an ‘ethnic penalty’ in relation to higher class outcomes; but for Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, this penalty persisted at all levels of education. These findings challenge the notion that a more equal society can be achieved simply through promoting equality of opportunity through education. Introduction The extent to which Britain is an open society has been a major concern of sociological research for a number of decades (Glass, 1954; Halsey et al., 1980; Goldthorpe et al., 1987; Marshall et al., 1997; Heath and Payne, 2000; Gershuny, 2002). Attention has focused both on the role of class background in determining future life chances, and also on how that advantage is maintained through, or disrupted by, the increasing role of educational qualifications in determining occupational position (Goldthorpe, 1997, 2003). Aspirations towards a meritocracy based on educational achievement (Blair, 2001) appear hard to achieve. However, class advantage and educational success do not necessarily operate to the same effect across groups. Ascertaining how different forms of advantage or disadvantage intersect is inforThe Sociological Review, 55:3 (2007) © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review. Published by Blackwell Publishing Inc., 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, 02148, USA. Lucinda Platt Chinese No Academic or Professional Qualifications Other Black Black African 1+ O level or equivalent Black Caribbean 5+ O levels or equivalent Bangladeshi 2+ A levels or equivalent or higher Pakistani Indian Other Qualifications White British 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Figure 1 Highest level of educational qualifications across selected ethnic groups, 2001, all aged 16–74, England and Wales Source: 2001 Census, Commissioned Tables. mative both about the nature of stratification and equality within a society and can help us to understand the processes by which some groups and not others achieve success – and whether these processes are particular or more general. While class immobility is generally taken to indicate a closed (or ‘nonmeritocratic’) society, taking account of ethnicity complicates that understanding (Hout, 1984; Platt, 2005a). If minority groups reflect equivalent immobility in their own class transitions, then this may be indicative of a form of parity at the level of ethnicity even if not of class background. By contrast, if minority groups show much more mobility up and down the class structure, then that may give us cause for concern about the extent to which advantage achieved by one generation can be sustained into the next, and thus lead us to question equality of opportunity across ethnic groups. Educational achievement is clearly crucial to minority group success. The achievement of higher levels of qualifications across generations is a feature of most groups’ experience, even if there remains an educational ‘deficit’ or penalty for some groups. Figure 1 illustrates the variation between groups in the distributions of their highest qualifications. This is echoed in the results for 16–24 year olds (Figure 2), though there are fewer with no or limited qualifications for all groups given the increase in qualifications for younger generations. 486 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review Making education count Chinese Other Black No Academic or Professional Qualifications Black African 1+ O level or equivalent Black Caribbean 5+ O levels or equivalent Bangladeshi 2+ A levels or equivalent or higher Pakistani Other Qualifications Indian White British 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Figure 2 Highest level of educational qualifications across selected ethnic groups, 2001, aged 16–24, England and Wales Source: 2001 Census, Commissioned Tables. Crown Copyright. Accounts attempting to explain the situation of what are commonly regarded as the more successful of the UK’s minority ethnic groups (Indian/ East African Asian and Chinese) have often stressed a particular groupspecific attachment to education (Modood, 2004; Archer and Francis, 2006). However, commitment to education is also well-attested among groups that achieve less educational success. The higher rates of staying on in school among minority groups, including ‘less successful’ minority groups such as Caribbeans and Pakistanis, suggest that minority group members are well aware of the importance of education as a necessary (if not sufficient) route to success, and that they are highly motivated (DfES, 2004; Heath and Yu, 2005). Moreover, the relationship between educational qualifications and occupational outcomes is not necessarily straightforward. Levels of educational qualifications across groups may help explain patterns of occupational success; but they are insufficient to explain unemployment rates as they differ by ethnic group (Heath and Yu, 2005). Excess unemployment among minority ethnic groups persists even when education is controlled for (Blackaby et al., 1999). This finding is supported when UK-born are distinguished from those born outside the UK (Blackaby et al., 2005) and when background factors that may provide additional protection against unemployment are taken into account (Platt, 2005b). And lack of motivation among those who fare less well in employment is not supported by the evidence (Thomas, 1998). © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 487 Lucinda Platt Variation in educational qualifications, then, only accounts for part of the differences in social class outcomes between groups. Some would attribute the remaining difference to discrimination (e.g. Blackaby et al., 1998). However, that not only assumes that all other relevant factors have been captured in the models, but, with its stress on individual level discrimination, discounts a role for structural processes perpetuating disadvantage, that may or may not be ethnically specific. Heath and McMahon (1997), in coining the term ‘ethnic penalty’, were more cautious, arguing that it contains both discrimination and further, unmeasured, characteristics that vary with ethnicity. One of the unmeasured characteristics they posit is parental class background. This brings us to the role of class background in determining or influencing both educational and occupational success. The few studies that have been carried out on ethnic differences which take account of class background indicate that class origins are important for minority groups but that an ‘ethnic penalty’ remains – at least for some groups (Heath and Ridge, 1983; Heath and McMahon, 2005; Platt, 2005a). However, the former two studies were problematic in their measurement of origin class being predominantly pre-migration, while Platt (2005a) did not consider education. It is also important to identify whether educational qualifications operate consistently across groups and whether ethnic penalties can be found at all levels of educational achievement. The analysis presented here, therefore, takes account of background factors, including parental class, that are measured in the same country (England/ Wales) and educational system and in the same time period and across a range of ethnic groups. By investigating the intersection of class and ethnic background and the role of education it aims to refine our understanding of mobility processes and of the diverse fortunes of Britain’s ethnic groups. Data and study design The data for this paper come from the ONS Longitudinal Study, a recordlinkage study of one per cent of the population of England and Wales. It was initially obtained by taking a sample of the 1971 Census, based on those born on one of four birth dates (day and month). At each subsequent Census, information from samples taken using the same sampling criteria is linked where possible. Between censuses, members are added to the study by linking information on births and immigrations, again using the same sampling criteria. Information on death and emigration from England and Wales is also linked to the study. No further information is linked for sample members who have died or emigrate, although linkage recommences for members who return to England and Wales. The paper examines two combined cohorts of LS members, those who were children aged 4–15 in 1971 and those who were aged 4–15 in 1981. The pooling of two cohorts was undertaken primarily to increase sample sizes of the 488 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review Making education count minority groups. The children’s origins, both in terms of social class origins and other family/parental characteristics, were measured in 1971 or 1981, since the characteristics of co-resident household members and their relationship to the study member, in this case parents, are included in the LS at each wave. Their achieved class position was measured at 2001 (when they were aged between 24 and 45). Thus, this analysis benefits from a prospective design: measurement of origins is observed directly and is therefore not subject to recall error and, particularly important for minority ethnic groups, is known to be their postmigration situation in England and Wales rather than that prior to migration. Variables constructed to summarise characteristics associated with study members’ origins (when they were children in 1971/81) were: • Parents’ social class: using the three-category CASMIN schema, that is service (the highest social class), intermediate, working, and other (where respondents did not fit one of the former classes). Where both parents were co-resident with the study member and occupied different occupational class positions, the higher of the two was allocated as the parental social class (the ‘dominance approach’); • housing tenure (owner occupation, local authority housing, private rented); • car ownership in household (0 cars, 1 car, 2 or more cars); • parents’ qualifications (no mother (father), mother (father) has no higher qualifications, mother (father) has higher qualifications). At 2001, variables constructed to measure study members’ own characteristics were: • social class: according to the NS-SeC (the 2001 equivalent of the CASMIN schema). The dominance approach was again used to allocate destination class where the study member and a co-resident partner occupied different class positions. The implications of this approach for the possibility of analysing outcomes for men and women separately are discussed below. This study focuses on attainment of professional / managerial class positions compared to any other outcome (including unemployment or inactivity). • ethnic group: based on the 1991 ethnic group classification, but modified to differentiate those of migrant parentage from those of non-migrant parentage. The minority groups were required to have at least one migrant parent and the white majority group was required to have both parents UK born. In addition, a white migrant group was created based on white 1991 ethnicity combined with both parents being migrants. A residual category comprised those who did not fit these combinations of (non)migrant parentage and ethnicity.This paper concentrates on the five largest groups, for which discrete analysis is possible and meaningful, namely: white non-migrant, Caribbean, Indian, Pakistani and white migrant ethnic groups. © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 489 Lucinda Platt • partnership status (this was particularly important as the allocation of class using the dominance approach meant that those who were partnered would be classified by their partner’s class if it was higher). • education (recoded into four categories of highest qualification: none, NVQ Level 1 (1–4 GCSEs grades A* to C or equivalent), NVQ Level 2 (5+ GCSEs grades A* to C or equivalent), NVQ Level 3 and above (2 A’ levels or equivalent, and above). Variables to take account of whether origins were observed at 1971 or 1981, the age of the study member in 1971 or 1981, grouped into three bands (4–7, 8–11 and 12–15), and the combination of these two variables as birth cohorts, and the concentration of minorities in the ward where the study members were growing up in 1971 or 1981, divided into two bands, low or high, were also created and included in the analysis. These offered checks on the impact of differential outcomes by age; on the possible period effects of measuring parents’ characteristics at two different times – 1971 and 1981; and on some of the effects associated with growing up in different areas or sorts of ‘neighbourhood’. These controls, while contributing to the fit of the models, did not reveal note-worthy trends and therefore, while included in the models, are not included in the discussion of results. The sample was also differentiated by sex. However, because of the way outcome class was constructed using the dominance approach, for those who were partnered the class allocated was that of the couple rather than that of the individual. This means that the sex variable only differentiated effectively between those who were single in 2001. The approach to allocating class position was adopted as it is class rather than occupation which is the outcome of interest, and it is not meaningful to treat people’s class position as independent of their partner. By implication it therefore regards marriage as well as individual occupational success as a potential route to upward mobility. The approach does have the disadvantage, though, that gendered trajectories or differences in the influence of background on outcome for men and women cannot be clearly distinguished. It also means that those groups where women are more likely to be economically inactive following marriage, in particular Pakistanis and Bangladeshis (Dale et al., 2004), have immediately lower chances of the female spouse raising the class position of the couple, with implications for both partners. This is a point I return to when considering the results. Results Effect of education on intergenerational class mobility The distribution of the main variables across the five largest minority groups considered in this analysis is shown in Table 1.1 The distribution across the white non-migrant group is comparable to that for the sample, given their 490 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review Making education count Table 1 Percentage distributions (column %) of family characteristics at origin in 1971/81 and own characteristics in 2001 White non- Caribbean migrant % % Origin Characteristics: 1971/81 Origin (parents’) Class: Service Origin (parents’) Class: Intermediate Origin (parents’) Class: Working No co-resident mother Mother with no higher qualifications Mother with higher qualifications No co-resident father Father with no higher qualifications Father with higher qualifications Owner occupied housing Local authority housing Private rented housing No car 1 car 2 or more cars Own characteristics: 2001 Destination (own) Class: professional/ managerial Destination Class: Intermediate Destination Class: Routine/manual Destination Class: Unemployed and Other N = 2,110 Indian % Pakistani White % migrant % N = 2,005 N = 1,033 N = 4,480 29 13 13 7 18 19 9 13 16 19 52 78 74 77 63 100 2 90 100 4 87 100 2 94 100 5 93 100 5 84 8 9 4 2 11 100 8 78 100 21 74 100 5 84 100 5 90 100 18 72 14 4 11 5 9 100 57 100 50 100 84 100 87 100 56 33 10 100 28 55 17 100 N = 125,014 40 10 100 60 35 5 100 N = 1,547 9 7 100 44 47 9 100 N = 1,691 8 5 100 50 45 5 100 N = 779 32 12 100 48 42 10 100 N = 3,675 48 39 55 32 50 19 21 18 22 20 24 20 18 21 19 9 20 9 25 11 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 491 Lucinda Platt Table 1. cont. White non- Caribbean migrant % % No qualifications Level 1 (1–4 GCSEs at A* to C grades, or equivalent) Level 2 (5+ GCSEs at A* to C grades, or equivalent) Level 3 and above (2 A’ levels plus, or equivalent) Group % of total sample (row percent) Indian % Pakistani White % migrant % 100 15 29 100 11 30 100 10 20 100 20 21 100 14 26 25 26 19 19 25 31 34 51 40 35 100 100 100 100 100 92 1.1 1.2 0.6 2.7 Source: ONS Longitudinal Study, author’s analysis. numerical dominance (over 90 per cent of the total sample). We can see that far more children from white non-migrant backgrounds were growing up in service class families than were children from minority ethnic groups in 1971/ 81. Conversely those from minority group backgrounds were heavily concentrated in working class families as children. The transformation of the class structure meant that almost half of the sample were living in professional or managerial class families in 2001, though this varied by ethnic group with 55 per cent of Indians but only 32 per cent of Pakistanis in this position. Few from any group had either father or mother with higher qualifications; but Caribbeans and white migrants were more likely to be growing up without a co-resident father, reflecting both particular patterns of migration, with many Caribbean women migrating independently in the post-war era, and post-migration living arrangements. Own qualifications in 2001 showed that most groups had only a small proportion with no qualifications, though those without qualifications amounted to one in five of the Pakistani sample. Those with level three qualifications and above were around one in three among white non-migrants, white migrants and Caribbeans, but rose to two in five among Pakistanis and over half of Indians. So what is the relationship between these characteristics? Can the class outcomes be understood in terms of particular patterns of experience while growing up: that is, experience of parental class, parental education and relative affluence (as proxied by housing tenure and car ownership)? Once we take account of these relevant formative experiences do we cease to see differences by ethnic group – or conversely does ethnic group ‘trump’ class in 492 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review Making education count its impact on life chances? Are educational qualifications able to turn around class patterns of mobility, or are qualifications more an expression of advantaged backgrounds? To investigate these questions, binary logistic regression models were estimated to ascertain the presence of ethnic group and class origin effects and the extent to which they were modified by educational qualifications (Table 2). Model 1, which explored the relationship of background to professional or managerial class outcomes without taking account of study members’ own education, indicated class background was strongly associated with class outcomes, over and above the effect of having a highly educated parent or being relatively well-resourced. These results accord with research that has shown that class background remains important in determining life chances (Heath and Payne, 2000). Additionally, it showed that nearly all the minority groups experienced greater upward mobility (or retention in the higher class) relative to white non-migrants with comparable backgrounds. This is indicated by the positive and significant coefficients for these groups. This would support an argument for these minorities having had their ‘true’ class position suppressed in the first generation following migration to the UK. There has been some evidence that migrants’ class position was depressed following arrival in Britain, as a result of either discrimination or lack of familiarity with the labour market, at around the time that parents’ class was observed in this study (Daniel, 1968; Heath and Ridge, 1983). If that is the case, then what we might be seeing is simply a reassertion of an underlying class position. Alternatively (or additionally), this result would accord with the theory that the migrant generation focuses motivation on the achievements of the second generation (Archer and Francis, 2006; Card, 2005). However, the Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups show the opposite pattern. They experience less social class success than even their heavy concentration in the working classes of the migrant generation (see Table 1) would lead one to expect. Either their underlying class position is weaker than that of the other minority groups, or they are subject to additional barriers or obstacles to progress. When study members’ own education is included (Model 2), the strong reduction in the size of the positive ethnic group effects and their lack of significance indicates that the upward mobility found in Model 1 is achieved through the second generation gaining educational qualifications. This could be explained through particular motivation to achieve associated with minority ethnic groups, mentioned above, or, once again, through ‘bounceback’ from suppressed class position in the migrant generation, meaning that the level of qualifications within lower class positions mimics those that might be expected at higher class positions. These two aspects of aspirations and suppressed class position might also intersect at the level of group norms, resources and attitudes, sometimes conceived as ‘ethnic capital’ (Borjas, 1992), that both reinforces a culture of aspiration and supports the upward mobility and educational attainment of the second generation. © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 493 Lucinda Platt Table 2 Logistic regressions of probability of professional/managerial destination in 2001, controlling for individual and background characteristics Model 1 Coefficients (SE) Ethnic group (baseline is white non-migrant) Caribbean 0.306 Black African 0.469 Indian 0.460 Pakistani -0.525 Bangladeshi -0.274 Chinese and other 0.491 White migrant 0.318 Model 2 Coefficients (SE) -0.037 -0.001 0.105 -0.792 -0.465 0.078 0.142 (0.076)*** (0.246)* (0.068)*** (0.103)*** (0.245) (0.106)*** (0.044)*** Sample member’s qualifications (base is 0) Lower (level 1) Middle (level 2) Further (level 3+) Origin class: base is working Service class 0.547 (0.018)*** Intermediate 0.056 (0.017)*** Other -0.204 (0.035)*** Mother’s qualifications (base no qualifications) No co-resident mother -0.198 Mother with qualifications 0.425 Father’s qualifications (base no qualifications) No co-resident father 0.232 Father with qualifications 0.532 (0.081) (0.268) (0.069) (0.111)*** (0.237)* (0.109) (0.047)** 1.013 (0.027)*** 1.466 (0.027)*** 2.765 (0.028)*** 0.330 (0.019)*** 0.012 (0.018) -0.102 (0.038)** (0.047)*** (0.025)*** -0.106 (0.052)* 0.119 (0.027)*** (0.029)*** (0.022)*** 0.143 (0.032)*** 0.220 (0.024)*** Tenure at origin (base is owner occupation) Local authority -0.576 (0.015)*** Private rented -0.316 (0.022)*** -0.286 (0.017)*** -0.171 (0.024)*** Car ownership at origin (baseline is no cars) 1 car 0.277 2 or more cars 0.406 Constant -1.101 LR chi2 (df) 12,928 Chi2 Change (df) 0.174 0.287 -2.430 22,448 9,520 N (0.016)*** (0.022)*** (0.024)*** (28)*** (0.017)*** (0.024)*** (0.034)*** (32)*** (4)*** 128,520 Source: ONS Longitudinal Study, author’s analysis. Notes: *** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05. Standard errors are adjusted for repeat observations on persons. The regression models were run (a) using dummies to represent missing cases for parental qualifications, own qualifications and housing tenure and (b) excluding all cases with missing values. The advantage of the former approach is that it maintains the sample size, however, it may do so at the expense of distorting the estimates (Allison, 2002). Checks confirmed however that there was little difference between the estimates based on exclusion of cases with missing values or on substitution of dummies for missing values. These estimates use dummies, but for brevity the coefficients for the dummies are not given in this Table. Controls for age/cohort, sex, partnership status and ethnic minority concentration in ward where living in 1971/1981 were also included but are not reported here for concision. Full tables are available from the author on request. 494 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review Making education count However, the effect for Pakistanis and Bangladeshis becomes stronger (a more negative coefficient) once education is included, indicating that their chances of professional managerial success are substantially worse than their white non-migrant peers at the same level of education. If some sort of underlying class position impacted on the achievement of qualifications among the minority groups and thus determined the levels of professional managerial class attainment, then we would expect to see lower qualifications levels among these two groups. Consequently, their negative coefficient would become weaker and non-significant, meaning that their lower chances of successful class outcome were similar to white non-migrants with comparable levels of qualifications and similar backgrounds. Instead, the acquisition of educational qualifications seems of smaller benefit to these minority groups. Why should educational qualifications be less powerful for some groups than for others? The barriers to success offered by discrimination is one obvious reason; but this would not immediately explain why the impact was borne particularly by certain minority groups. It may be that there is diversity within institutions in their influence in the labour market: at the upper end, attention has been drawn to the relative salience of a degree from Oxbridge compared to a degree from a new university, for example (Shiner and Modood, 2002). It may also stem from the greater level of support higher class origins can give to staying in education after 18, given that the highest qualification level in this analysis combines A’ levels and degrees. A further contributory factor in this result is likely to be the inability of educational qualifications to lead to higher occupational outcomes if withdrawal from the labour market takes place. Thus if women with high qualifications withdraw from the labour market following marriage to those in intermediate or routine occupations, then their qualifications will not be congruent with their (couple) class position. Nor will they be able to create upward mobility for their partners. Given that Pakistani and Bangladeshi women are more likely than women from other groups to withdraw from the labour market following marriage (Dale et al., 2004), this is more of an issue for these groups. In addition, girls from these groups may be more constrained in relation to the higher education institutions they attend and subsequent opportunities (Dale, 2002). However, marriage patterns themselves are associated with educational qualifications (Lindley et al., 2006), and examination of the differences between individual and couple class outcomes (not illustrated) indicated that while this factor played a role it could not explain more than a small part of the observed ‘penalty’. In addition, if ethnic capital can be important in enabling upward mobility, it may also be relevant to our understanding of the more limited success of certain groups. Certain groups may be less well resourced with Borjas’ type of ethnic capital. Moreover, ethnic capital is often also conceived of as a form of social capital; and within the social capital literature the distinction between ‘bridging’ and ‘bonding’ forms of capital, the one which eases upward mobility the other which inhibits it, is often regarded as crucial. It is clear that the © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 495 Lucinda Platt relative role of bridging and bonding must vary at different points in the class distribution (Lin, 2001). Those who start from a more disadvantaged position may be ill-placed to secure upward social mobility. And this disadvantage may be coterminous with high levels of concentration, with the Pakistani and Bangladeshi minority groups being relatively highly concentrated compared to other minority groups. Both positive and negative attributes have been associated with so-called ‘enclaves’: they have been argued both to inhibit assimilation and thus upward mobility and to provide a resource for minority ethnic groups. However, Clark and Drinkwater (2002) failed to observe in Britain the positive effects posited for enclaves. And Simpson has challenged the whole idea that the more disadvantaged minority ethnic communities opt for ‘self-segregation’ (Simpson, 2004). At the same time, more successful minority group members from certain groups may, in the process of expressing social mobility through geographical mobility, select into co-residence in more prosperous areas (Dorsett, 1998), and thereby facilitate the future mobility of their own and others’ children. Individuals from certain groups may thus be better served by geographical distribution and group histories as well as their own characteristics to exploit the potential of ‘bridging’ capital to effect upward mobility. This would be consistent with the theory that ethnic penalties operate differently at different structural positions and with Portes and Zhou’s (1993) theory of ‘segmented assimilation’. To try to get a closer understanding of some of these issues of differential impact, there are two lines of inquiry to pursue. The first is to examine the role of class in more detail and whether it operates in a similar way across groups; the second is to explore whether there are different ‘ethnic penalties’ at different levels of qualifications. Two approaches are used: first the intersections of ethnicity and class and ethnicity and education are explored within the main model; and second, separate models are estimated for the five main ethnic groups. Class background and ethnicity The assumption of the models in Table 1 has been that the class effects operate consistently across the values of the other variables, in particular across the different ethnic groups. However, earlier research has suggested this may not be the case (Platt, 2005a). The speculations raised in this paper both about ‘bounceback’ and about the role of ethnic capital have posited a situation in which class background means different things for different groups. Given the dominance of the white non-migrant majority within the sample, the class effects observed in Table 2 will be driven by those that apply to this group, disguising potential differences across the minority groups. Therefore, a set of dummy variables was created, which combined the effect of class origin and ethnic group, using white non-migrant of working class origin as the baseline category. These were included in the model in place of the ethnic group and 496 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review Making education count Table 3 The effects of ethnicity and origin class (at 1971/81) on the chances of being in the professional or managerial classes in 2001 White non-migrant of service class origin White non-migrant of intermediate class origin Caribbean of service class origin Caribbean of intermediate class origin Caribbean of working class origin Indian of service class origin Indian of intermediate class origin Indian of working class origin Pakistani of service class origin Pakistani of intermediate class origin Pakistani of working class origin White migrant of service class origin White migrant of intermediate class origin White migrant of working class origin N Model 1 Coefficient (SE) Model 2 Coefficient (SE) 0.559 (0.018)*** 0.060 (0.018)*** 0.341 (0.020)*** 0.016 (0.019) 0.258 -0.106 0.410 1.00 0.476 0.451 0.151 -0.396 -0.461 0.674 0.419 0.361 (0.188) (0.246) (0.088)*** (0.189)*** (0.177)** (0.080)*** (0.403) (0.244) (0.124)*** (0.106)*** (0.100)*** (0.056)*** -0.120 -0.277 0.128 0.486 -0.006 0.113 -0.511 -0.882 -0.654 0.205 0.305 0.166 (0.199) (0.256) (0.095) (0.175)** (0.181) (0.081) (0.369) (0.253)*** (0.135)*** (0.114) (0.110)** (0.059)** 128,520 Source: ONS Longitudinal Study, author’s analysis. Notes: as for Table 2. class background variables. The coefficients for these dummy variables are given in Table 3, focusing on just the three main origin classes and on the five ethnic groups which form the focus of this paper. If the effects of relatively privileged or relatively disadvantaged origins were consistent across groups we would expect to see a positive and significant effect for being of service class origin for all groups, and a statistically insignificant effect of being from a working class background for all the minority groups. Instead, in the model without education, we see that for Caribbeans the effects seem to work in the opposite direction, showing greater levels of upward mobility from the working class, but with privileged class origins having little bearing on subsequent outcomes. This impression is enhanced when educational qualifications are taken into account, as the coefficient for the higher two classes becomes negative (even if not statistically significant at conventional levels). This points to an inability of those who grow up in more privileged backgrounds to retain that advantage, which provides potential evidence of discriminatory barriers to success. For Indians and white migrants, successful outcomes are achieved relative to the white working class from all origin positions, though the effect is graduated, suggesting that class background plays a role within the groups. And for Pakistanis, not only is there no advantage (as for the Caribbeans) from advantaged origins, but those from © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 497 Lucinda Platt working class origins are less likely than their white non-migrant counterparts to end up in professional or managerial positions. The large deficit among those from working class backgrounds supports the notion that there is some kind of segmentation, whereby those growing up in a relatively disadvantaged position, which is not a consequence of class suppression to the same extent as it is for other groups (Smith, 1977), face additional barriers in terms of class mobility. When education is included in the model (Column 2 of Table 3) we see, as we did in Table 2, the way in which upward mobility for the Indians, white migrants and, to a lesser extent, the Caribbeans is achieved through education. We can also see that, for these groups, class of origin plays a much more circumscribed role, once its impact on educational qualifications has been achieved. For the Indians and white migrants, then, there appears to be the ability to retain class advantage through educational qualifications, while those in less privileged class positions also achieve at unexpected levels to gain good social class positions. This would fit with an idea of ethnic capital as extending beyond individual circumstances and having a wider role in group outcomes. Educational qualifications and ethnicity We now go on to explore the possibility that different levels of educational qualifications have different salience for minority ethnic groups. That is, while high qualifications might be a passport to success across groups, do low qualifications carry with them an additional penalty that would help us to understand the particular lack of upward social mobility experienced by the Pakistanis in our sample? Figure 3, which is based just on raw counts, gives some support to the notion of differential impact for minority groups (but not white migrants) with no qualifications. Relatively small proportions with no qualifications from the Pakistani, Indian and Caribbean groups end up in the professional or managerial classes compared to the white groups. The ethnic penalty does, then, seem greater for the least advantaged; and to the extent that any minority group is concentrated among those with no qualifications, they will then suffer disproportionately. But for lower qualifications (no qualifications plus level 1 qualifications), the differential impact persists only for the Pakistani group, rather than for all the minority groups illustrated.2 Caribbeans and Indians, even with the rather minimal certification offered by having level 1 qualifications, seem able to catch up with rates of entry into the professional and managerial classes of the white majority. But we see that only 10 per cent of Pakistanis and 14 per cent of Bangladeshis with lower levels of qualifications end up in the professional or managerial classes. For those with higher qualifications, there seems also to be some degree of differentiation, with the disadvantage experienced by Pakistanis and Bangladeshis also continuing at this level. Interestingly, though, here they are 498 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review Making education count 17 white migrant 29 65 8 Ethnic group Pakistani no qualifications lower qualifications higher qualifications 10 47 10 Indian 28 69 9 Caribbean 26 51 15 white non-migrant 29 64 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 % Figure 3 Per cent in professional or managerial classes by ethnic group and broad level of qualifications Source: ONS Longitudinal Study, author’s analysis. Notes: ‘lower’ refers to no or level 1 qualifications; ‘higher’ refers to level 1 or 2 qualifications. joined by the Caribbeans who appear, therefore, better able to overcome the ethnic penalty at lower compared to higher levels of qualifications. Thus, the picture seems to be not simply that minority groups need qualifications to succeed and are peculiarly disadvantaged at lower levels of qualifications. Rather, qualifications, and different levels of qualifications, themselves appear to be less salient for outcomes for those from certain minority ethnic groups. However, this does not take account of the other factors impacting on social class outcomes that we have argued to be important, notably the parental context experienced while these respondents were growing up. To explore the relevance of different levels of qualifications in the multivariate context, therefore, a model was estimated which included interactions between ethnicity and educational qualifications (controlling for the other variables in the models in Table 2). Given the problems with meaningful interpretation of interaction effects (Ai and Norton, 2003), predicted probabilities and their associated 95 per cent confidence intervals were calculated from the model at various levels of class background and educational qualifications to illustrate the extent to which these interactions made a difference. These probabilities are illustrated in Figure 4 for lower qualifications and Figure 5 for higher qualifications. In both figures, characteristics other than ethnic group are held constant. The © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 499 Lucinda Platt white non-migrant -- with interaction Ethnic Group Caribbean -- with interaction Indian -- with interaction Pakistani -- with interaction white migrant -- with interaction .1 .2 .3 .4 .5 .6 Predicted probability prof/man class Figure 4 Predicted probabilities from simple model and model with ethnicity-education interaction, at lower educational qualifications Source: ONS Longitudinal Study, author’s analysis. Notes: other characteristics are male, partnered, in owner occupation, parents without higher qualifications, working class background, low ethnic minority density in ward where grew up, growing up in a household with one car, aged 8–11 in 1971. Standard errors have been adjusted for clustering on individuals. probabilities illustrated are those for being in the professional or managerial classes based on, first, a model that includes a simple binary variable for lower or higher qualifications and, second, a model which interacts this variable with ethnic group. If educational qualifications had a similar impact across groups then we would expect the predictions from the simple model and the interaction model to be similar at both lower and higher levels of qualifications. Instead we see, in Figure 4, that both Indians and Pakistanis experience substantially and significantly lower probabilities of professional managerial outcomes if they have lower educational qualifications according to the interaction model. Figure 5 shows that while the interaction model results in higher (though not statistically significantly different) probabilities at higher levels of 500 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review Making education count white non-migrant -- with interaction Ethnic Group Caribbean -- with interaction Indian -- with interaction Pakistani -- with interaction white migrant -- with interaction .5 .6 .7 .8 .9 Predicted probability prof/man class Figure 5 Predicted probabilities from simple model and model with ethnicity-education interaction, at higher educational qualifications Source: ONS Longitudinal Study, author’s analysis. Notes: as for Figure 4. education for both the Indians and the Pakistanis compared to the simple model, the net result for the two groups is very different. The probabilities for Indians at higher levels of qualifications outstrip those for the white majority suggesting a particular ability to capitalise on education (or the fact that their qualifications are at the upper end of the broad level 3+ band), while Pakistanis still lag behind the white majority in terms of their chances of professional or managerial class outcomes even when they have passed this threshold of qualifications. What we see then, is some evidence for a differential ethnic penalty, with greater obstacles at lower educational levels of qualifications. At the same time, we also see a large specific penalty for the Pakistani group, which cannot be fully accounted for by relative concentration at lower qualifications levels. We return to discussion of these results in the conclusion. First however, we turn to a consideration of models estimated separately for the minority groups to ascertain if they can help us to understand further the different roles of both class background and educational achievement. © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 501 Lucinda Platt The effects of education and background within groups Table 4 illustrates the main results for models of professional or managerial class outcome estimated separately for the five main ethnic groups. It shows that for the minority groups, once we take account of the fact that background may be channelled through educational achievement, parents’ class, educational and economic resources do not seem to play much of an additional role in the success of their children. They do appear to have an important additional role for the white majority, as we would expect from the pooled model.3 There is some evidence for Indians that the economic resources indicated by car ownership provide an additional advantage. However, for this group the effects of housing tenure reverse the expected pattern, and are statistically significant. Those Indians who grew up in both local authority housing and private rented housing have increased chances of professional / managerial class outcomes relative to those who grew up in owner occupied housing. This supports the evidence that owner occupation is not such a clear indicator of economic position or relative advantage for South Asian groups as it is for the population as a whole (Phillips, 1997), especially given the way that owner occupation may constrain opportunities for geographical mobility. It may also suggest that there was some substitution by Indian parents in the 1970s and 1980s in relation to the allocation of resources between home ownership and the promotion of the success of their children by other means.4 Education, as noted before, is the primary route to upward mobility, and the coefficients for educational qualifications are large across the groups. However, we see among Pakistanis that having level 1 qualifications does not constitute an advantage over and above having no qualifications. It is only at levels 2 and 3 that qualifications increase the prospects of professional or managerial class outcomes relative to those from the same ethnic group with no qualifications. This is consistent with the raw differences in outcome by educational qualifications illustrated in Figure 3, and indicates that for this group obtaining any qualifications is not sufficient to improve life chances. There seem to be additional obstacles which mean that the effect of qualifications only become relevant at higher levels. This is also suggested by the apparently smaller coefficients for the effects of education on social class outcomes for this group compared to the other groups. However, cross-equation tests of the coefficients could not reject the possibility that they were same as those for the white non-migrant group (perhaps as a result of the relatively small sample size for the Pakistani group). Such comparability was also the case for the coefficients for the Caribbean and white migrant groups. By contrast, the education coefficients for the Indian group were all found to be significantly different from those for the white non-migrant group. Those of Indian ethnicity therefore not only get more qualified than the other groups – including by channelling background advantage into education, but seem particularly able to capitalise on their qualifications at all levels in relation to social class outcomes. 502 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review -0.186 (0.179) 0.066 (0.265) 0.178 0.445 -2.521 217 Tenure at origin (base is owner occupation) Local authority -0.298 (0.018)*** Private rented -0.193 (0.025)*** Car ownership at origin (base = none) 1 car 0.180 2 or more cars 0.292 Constant -2.427 LR chi2 (df) 31,402 115,478 Source: ONS Longitudinal Study, author’s analysis. Notes: as for Table 2. N 0.169 (0.241) 0.400 (0.372) Father’s qualifications (base = none) No co-resident father 0.166 (0.034)*** Father with qualifications 0.233 (0.025)*** 1,010 (0.170) (0.329) (0.454)*** (24)*** 0.142 (0.402) 0.281 (0.263) Mother’s qualifications (base = none) No co-resident mother -0.101 (0.054) Mother with qualifications 0.116 (0.029)*** (0.018)*** (0.025)*** (0.035)*** (24)*** -0.322 (0.233) -0.373 (0.264) 0.176 (0.277) 1.796 (0.435)*** 2.102 (0.437)*** 3.137 (0.432)*** Caribbean 0.336 (0.020)*** 0.015 (0.019) -0.128 (0.041)** Origin class (base = working) Service class Intermediate Other Study member’s qualifications (base = 0) Lower (level 1) 1.009 (0.028)*** Middle (level 2) 1.451 (0.028)*** Further (level 3+) 2.752 (0.030)*** White non-migrant 0.334 0.313 -3.035 419 1,287 (0.156)* (0.275) (0.435)***. (24)*** 1.051 (0.276)*** 0.550 (0.276)* 0.064 (0.427) -0.044 (0.268) -0.206 (0.469) 0.508 (0.425) 0.190 (0.262) -0.212 (0.230) 0.153 (0.344) 1.904 (0.372)*** 2.348 (0.373)*** 4.124 (0.377)*** Indian 0.255 0.314 -3.027 150 557 (0.255) (0.559) (0.599)*** (24)*** 0.239 (0.404) 0.548 (0.485) 1.222 (0.648) -0.083 (0.504) 0.059 (0.649) 0.070 (0.836) 0.085 (0.463) -0.246 (0.308) -1.321 (0.467)** 0.536 (0.456) 1.465 (0.444)*** 2.971 (0.399)*** Pakistani (0.103) (0.170) (0.203)*** (24)*** 2,893 -0.005 0.189 -2.234 793 -0.216 (0.111)* 0.024 (0.140) -0.153 (0.145) 0.082 (0.176) -0.217 (0.222) 0.106 (0.170) 0.111 (0.143) 0.169 (0.129) 0.070 (0.169) 0.805 (0.175)*** 1.680 (0.175)*** 2.777 (0.178)*** White migrant Table 4 Logistic regressions of probability of professional/managerial destination in 2001, controlling for background and individual characteristics, by ethnic group Making education count 503 Lucinda Platt Discussion So how do we understand these results and what are their implications? The situation in which children grew up, including their parents’ characteristics and social class, cannot on its own account for differences in the outcomes of those from different ethnic groups. Indeed while background remains an important determinant of success for the white group, the minority groups predominantly represent a much more ‘meritocratic’ profile than the majority, with educational qualifications being the determinants of success. For certain groups (Indians), any existing background advantage is channelled through education, while for others (Caribbeans) background appears simply irrelevant. But for all minority groups, attainment of qualifications is disproportionate to that expected from class background when compared with the white majority; and for all minority groups bar the Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, education provides the means to higher rates of upward mobility than those from the white majority from the same cohort and with the same background achieve. The findings suggest both common processes across minority groups – attention to achieving qualifications, and relative disadvantage for those with no qualifications compared to the majority – as well as distinct patterns which seem to be group-specific. Bringing the various results together, we can characterise these distinctive patterns and consider their implications for the meritocratic ideal – if ideal it is (Aldridge, 2001) – in the following way. The patterns for the white non-migrant majority refute the notion that Britain is a meritocracy. Class and other aspects of background continue to be relevant to individuals’ social class outcomes. And this is the case even after own educational qualifications are taken account of.These findings of a society stratified by class set the context for the experience of other groups. White migrants would appear to represent the immigrant success story. They achieve upward mobility from predominantly working class backgrounds via means of educational qualifications. At the same time they reflect or absorb existing patterns of stratification insofar as those from more privileged backgrounds do better than those from working class backgrounds, by acquiring equivalently higher rates of qualifications. Thus, employing the language of narratives of assimilation (Portes and Zhou, 1993), they ‘assimilate’ both in relation to outcomes and in relation to social processes. The Caribbean picture is one of within-group meritocracy in a nonmeritocratic context. Education brings returns that are roughly commensurate with those for the population as a whole; and, except for those with no qualifications, these returns are not significantly enhanced or reduced at higher or lower levels for this group. Class background brings no advantage, even before education is considered. However, this suggests that the expected returns from class advantage, such as networks and contacts, are unavailable to this group. The relatively geographically dispersed and socially integrated profile of this group (Peach, 2005), may have costs in relation to limited ability 504 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review Making education count to draw on forms of ‘ethnic capital’ at the same time as exclusion from majority-dominated elite networks and resources is enforced through discrimination. Retaining advantage across generations, which is often seen as central to higher class position and the strategies of its incumbents (Bourdieu, 1997) does not appear an option for this group, which therefore places them at a relative disadvantage. Moreover, educational qualifications may bring relative success, but do not protect from higher risks of ‘failure’ in terms of higher unemployment rates (Platt, 2005b). The Indian group makes effective use of qualifications to advance, getting particularly high returns for higher levels of qualifications. We may see evidence here for a positive role of ‘ethnic capital’ in, terms of group as well as individual resources, fostered by selected residential proximity (Dorsett, 1998), in securing a well-qualified second generation. Background resources, to the extent that they make themselves felt, also do so through education, thereby reinforcing a culture of attainment, and meaning that small section which grew up in a service class family has particularly high probabilities of professional or managerial class outcomes. The Pakistanis share with the Indians a clearer differentiation in chances at lower and higher levels of qualifications than the majority. However, in this case, it does not compensate for an overall high penalty in relation to social class outcomes. Class background does not constitute a strong influence on outcomes for this group, either positively or negatively, once educational level is taken into account. Thus this group would appear to experience both general ethnic penalties associated with lack of salience of class background and disadvantage at low levels of qualifications alongside a specific penalty which renders this group peculiarly disadvantaged. Group resources (or ‘ethnic capital’) would not appear to offer great potential in relation to upward mobility – though they may provide other benefits, such as protection against racism. The increasing levels of qualifications in this group may mean that, over time, the nature of group resources changes. Moreover, different patterns of migration for this group, with a greater proportion of the sample being found in the 1981 cohort compared to the 1971 cohort, may mean that their experience may become closer to that of the other minority groups over time. On the other hand, there appears to be the danger that in the face of both a class stratified and discriminatory society, those who are vulnerable on both these fronts will suffer disproportionately. On the one hand, the effective utilisation of educational qualifications among minorities bodes well for a future which is likely to continue to emphasise the importance of certification. On the other hand, lack of equality of opportunity, can compound the effect of the lack of equal starting positions that vex the whole meritocratic ideal, as demonstrated so effectively in Young’s (1958) original representation of a ‘meritocracy’. Received 7 March 2006 Finally accepted 1 December 2006 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 505 Lucinda Platt Acknowledgements The permission of the Office for National Statistics to use the Longitudinal Study is gratefully acknowledged, as is the help provided by staff of the Centre for Longitudinal Study Information & User Support (CeLSIUS), especially Julian Buxton. The clearance number for this paper is 4004a. The author however, retains full responsibility for the interpretation of the data. Census output is Crown copyright and is reproduced with the permission of the Controller of HMSO and the Queen’s Printer for Scotland. I am grateful for comments from seminar participants in Göteborg, and for the detailed and valuable feedback from two anonymous referees, as a result of which this paper was completely reworked. Notes 1 Distributions are not given for all minority groups to avoid risk of disclosure. 2 A similar pattern is observed for the Bangladeshi group, though these estimates have not been illustrated due to the small cell sizes on which they are based. 3 Though we should be alert to the fact that with a sample size of 115,000 many coefficients will achieve statistical significance at conventional levels as a result. 4 Though, owner occupation being such a dominant tenure among Indians, we should also recognise that those in rented accommodation are likely to be a quite specific sub-group. References Ai, C. and Norton, E.C., (2003), ‘Interaction terms in logit and probit models.’ Economics Letters, 80 (1): 123–129. Aldridge, S., (2001), Social Mobility: A Discussion Paper. London: Cabinet Office, Performance and Innovation Unit, April 2001. Archer, L. and Francis, B., (2006), ‘Changing classes? Exploring the role of social class within the identities and achievement of British Chinese pupils.’ Sociology, 40 (1): 29–49. Blackaby, D.H., Leslie, D.G., Murphy, P.D. and O’Leary, N.C., (1998), ‘The ethnic wage gap and employment differentials in the 1990s: Evidence for Britain’, Economic Letters, 58: 97–103. Blackaby, D.H., Leslie, D.G., Murphy, P.D. and O’Leary, N.C., (1999), ‘Unemployment among Britain’s ethnic minorities.’ Manchester School, 67: 1–20. Blackaby, D.H., Leslie, D.G., Murphy, P.D. and O’Leary, N.C., (2005), ‘Born in Britain: How are native ethnic minorities faring in the British labour market?’ Economic Letters, 88: 370–375. Blair, T., (2001), ‘Speech on the Government’s Agenda for the Future’, 8 February 2001. http:// www.pm.gov.uk/output/Page1579.asp. Borjas, G., (1992),‘Ethnic capital and intergenerational mobility’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107: 123–150. Bourdieu, P., (1997), ‘The forms of capital’, in Halsey, A.H. et al. (eds), Education: Culture, Economy, Society, Oxford: Oxford University Press: 46–58. Card, D., (2005), ‘Is the new immigration really so bad?’ The Economic Journal, 115 (507): F300–F323. Clark, K. and Drinkwater, S., (2002), ‘Enclaves, neighbourhood effects and economic outcomes: ethnic minorities in England and Wales’, Journal of Population Economics, 15: 5–29. Dale, A., (2002), ‘Social exclusion of Pakistani and Bangladeshi women’, Sociological Research Online, 7 (3). Dale, A., Dex, S. and Lindley, J.K., (2004), ‘Ethnic differences in women’s demographic, family characteristics and economic activity profiles, 1992–2002’, Labour Market Trends, 112 (4): 153–165. 506 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review Making education count Daniel, W.W., (1968), Racial Discrimination in England, Harmondsworth: Penguin. Department for Education and Skills [DfES] (2004), Youth Cohort Study: The activities and experiences of 18 year olds: England and Wales 2004, SFR 43/2004, 25 November 2004, London: DfES. Dorsett, R., (1998), Ethnic Minorities in the Inner Cities, Bristol: Policy Press. Gershuny, J., (2002), ‘Beating the Odds: Intergenerational Social Mobility from a Human Capital Perspective’, ISER Working Paper 2002:17, Colchester: ISER, University of Essex. Glass, D.V., (1954), Social Mobility in Britain. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Goldthorpe, J., (1997), ‘Problems of “meritocracy” ’, in Halsey, A.H., Lauder, H., Brown, P. and Stuart-Wells, A. (eds), Education: Culture, Economy, Society, Oxford: Oxford University Press: 663–682. Goldthorpe, J., (2003), ‘ “Outline of a theory of social mobility” revisited: The increasingly problematic role of education’, paper prepared for conference in honour of Professor Tore Lindbekk, Trondheim, April 25, 2003. Goldthorpe, J., Llewellyn, C. and Payne, C., (1987), Social Mobility and Class Structure in Modern Britain, 2nd edition, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Halsey, A.H., Heath, A.F. and Ridge, J.M., (1980), Origins and Destinations, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Heath, A. and McMahon, D., (1997), ‘Education and Occupational Attainments: The Impact of Ethnic Origins’, in Karn, V. (ed.), Ethnicity in the 1991 Census: Volume Four: Employment, Education and Housing among the Ethnic Minority Populations of Britain, London: Office for National Statistics. Heath, A. and McMahon, D., (2005), ‘Social mobility of ethnic minorities’, in Loury, G.C., Modood, T. and Teles, S. (eds), Ethnicity, Social Mobility and Public Policy: Comparing the US and U, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 393–413. Heath, A. and Payne, C., (2000), ‘Social Mobility’, in Halsey, A.H. with Webb, J. (eds), Twentieth Century British Social Trends, Basingstoke: Macmillan: 254–278. Heath, A. and Ridge, J., (1983), ‘Social mobility of ethnic minorities’, Journal of Biosocial Science Supplement, 8: 169–184. Heath, A.F. and Yu, S., (2005), ‘Explaining ethnic minority disadvantage’, in Heath, A.F. Ermisch, J. and Gallie, D. (eds), Understanding Social Change, Oxford: British Academy/Oxford University Press: 187–225. Hout, M., (1984), ‘Occupational mobility of black men: 1962 to 1973’, American Sociological Review, 49: 308–322. Lin, N., (2001), Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Lindley, J., Dale, A. and Dex, S., (2006), ‘Ethnic Differences in Women’s Employment: The changing role of qualifications’, Oxford Economic Papers, 58: 351–378. Marshall, G., Swift, A. and Roberts, S., (1997), Against the Odds? Social Class and Social Justice in Industrial Societies, Oxford: Clarendon Press. Modood, T., (2004), ‘Capitals, ethnic identity and educational qualifications’, Cultural Trends, 13 (2): 87–105. Peach, C., (2005), ‘Social integration and social mobility: segregation and intermarriage of the Caribbean population in Britain’, in Loury, G.C. Modood, T. and Teles, S.M. (eds), Ethnicity, Social Mobility and Public Policy: Comparing the US and UK, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 178–203. Phillips, D., (1997), ‘The housing position of ethnic minority group home owners’, in Karn, V. (ed.), Ethnicity in the 1991 Census: Volume Four: Employment Education and Housing among the Ethnic Minority Populations of Britain, London: The Stationery Office: 170–188. Platt, L., (2005a), ‘The intergenerational social mobility of minority ethnic groups’, Sociology, 39 (3): 445–461. Platt, L., (2005b), Migration and Social Mobility: The Life Chances of Britain’s Minority Ethnic Communities, Bristol: The Policy Press. © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review 507 Lucinda Platt Portes, A. and Zhou, M., (1993), ‘The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants’, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 530: 75–96. Shiner, M. and Modood, T., (2002), ‘Help or hindrance? Higher education and the route to ethnic equality’, British Journal of Sociology of Education, 23: 209–230. Simpson, L., (2004), ‘Statistics of racial segregation: measures, evidence and policy’, Urban Studies, 41 (3): 661–681. Smith, D.J., (1977), Racial Disadvantage in Britain: The PEP Report, Harmondsworth: Penguin. Thomas, J.M., (1998), ‘Who feels it knows it: work attitudes and excess non-white unemployment in the UK’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 21: 138–150. Young, M., (1958), The Rise of the Meritocracy, 1870–2033: An Essay on Education and Equality, London: Thames and Hudson. 508 © 2007 The Author. Journal compilation © 2007 The Editorial Board of The Sociological Review