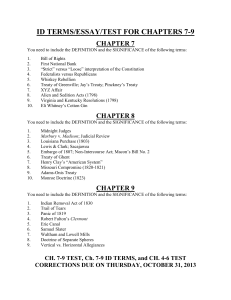

European Regulatory Alert New Treaty Makes it Easier to Challenge EU Law

advertisement

European Regulatory Alert 9 November 2009 Authors: Vanessa C. Edwards vanessa.edwards@klgates.com +44.(0)20.7360.8293 Neil A. Baylis neil.baylis@klgates.com +44.(0)20.7360.8140 K&L Gates is a global law firm with lawyers in 33 offices located in North America, Europe, Asia and the Middle East, and represents numerous GLOBAL 500, FORTUNE 100, and FTSE 100 corporations, in addition to growth and middle market companies, entrepreneurs, capital market participants and public sector entities. For more information, visit www.klgates.com. New Treaty Makes it Easier to Challenge EU Law The Lisbon Treaty, nine years in the making, received its last ratification on Tuesday 3 November 2009 with the signature of the Czech President. It will come into force on 1 December 2009. While having no immediate effect on the laws applying to companies doing business in Europe, it is intended to facilitate a more efficient law-making process and also to put in place constitutional changes which may enable the EU (comprising 27 Member States with a population of 500 million) to play a more significant role in commercial and political developments on the global stage. Specifically, the Lisbon Treaty makes a number of technical changes to the EU Treaty structure and some minor changes to the structure and functioning of the European Parliament, the European Commission and the European Court of Justice. In terms of substance the principal significant changes it makes are as follows. New Roles The Lisbon Treaty provides for a “permanent” President of the European Council. The President will be appointed for a two and a half year term and may be reappointed for one further term. To date, the Presidency of the European Council, which comprises the Heads of State or Government of the Member States and the President of the European Commission, has rotated between the Member States on a six-monthly basis. The European Council defines the general political direction of the EU. Its decisions are normally taken by consensus. The Treaty is vague about the exact nature of the role of President so that the first person in the role is likely to define its contours. Some Member States are keen to have a “big name” on the international stage (such as Tony Blair, the former UK Prime Minister) who would be comfortable representing the EU at international gatherings at the highest level, others prefer the idea of a lower-profile President who will focus more on moving forward the work of the EU with all that that entails in terms of chairing meetings, achieving consensus and the like (a number of names have been mentioned, including Jan Peter Balkenende, Dutch prime minister, Jean-Claude Juncker, Luxembourg’s premier, Paavo Liponnen, former Finnish prime minister and Herman von Rompuy, Belgian prime minister). The President will be elected by the European Council by what is known as “qualified majority voting” (“QVM”), essentially 55% of Member States representing 65% of the EU population. The Lisbon Treaty also provides for the appointment of a High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, who will also be the Vice President of the European Commission. The High Representative will be appointed by the European Council by QVM with the agreement of the President of the Commission. He will replace two current posts, the Commissioner for External Relations (Benita Ferrero-Waldner) and the High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy (Javier Solana). The new High Representative will conduct the EU’s common foreign and security policy and common security and defence policy, both which are decided unanimously at intergovernmental level. European Regulatory Alert The allocation of these posts will probably be decided at a special summit to be convened later this month, possibly next week. The various posts of Commissioner will also be decided at the same time. The President, the High Representative and the other members of the Commission must then be approved as a body by the European Parliament. These new roles could result in a greater consistency and coherency of EU policies, especially in the field of international politics. Enhanced Right to Challenge EU Legislation The right of individuals to seek judicial review of Community legislation is significantly broadened. Currently a person or company may challenge an EU measure before the EU courts only if he can show that it is of “direct and individual concern” to him. In most areas the European Court of Justice has interpreted the requirement of individual concern very narrowly so that legislation of general application (as opposed to a decision with specific addressees) cannot be challenged before the EU courts by persons or companies. The only course available to a party seeking review is to bring an action before a national court if that is permissible under national law and procedure and hope that the national court refers the matter to the EU courts, which can take a considerable time. The Lisbon Treaty will enable a person or company to bring a direct challenge before the European General Court (formerly the Court of First Instance) to a regulatory act of direct concern to him/it, provided that the act does not require further implementing legislation. This new avenue will provide a welcome and long-awaited opportunity for individual applicants to bring their concerns about the validity of an EU regulation in any of the numerous areas covered by EU law before the General Court. EU Replaces EC Currently the Treaty Establishing the European Community (1957), as its name suggests, established the European Community while the Treaty on the European Union (1992) established the European Union. personality (the EC has had legal personality since it was founded). The acquisition by an organisation of legal personality is a matter of international law, however, and most EC and international lawyers agree that the EU already has legal personality. Provision for a Member State to Withdraw The Lisbon Treaty lays down a procedure for a Member State to withdraw from the EU. Currently this is a matter for international treaty law requiring the consent of all other parties. EU Legislation Currently, most but not all EU legislation is passed by a procedure called “co-decision”, with the Council and the European Parliament being co-legislators. Certain areas, however, remain in the sole domain of the Council, often requiring unanimity. The Lisbon Treaty makes codecision with QMV in the Council the “ordinary legislative procedure” applying to all areas except foreign, security and defence policies, tax, certain social security matters affecting persons who have worked in more than one Member State and matters concerning the rights and interests of employed persons. Legislation in these areas will still require unanimity in the Council with the EP having a merely consultative role. However, nine or more Member States wishing to develop a policy which is not endorsed by unanimity may do so as a smaller group (without binding the other Member States) under the so-called “enhanced cooperation” procedure. The effect of the extension of the ordinary legislative procedure is that legislation in many areas which previously required unanimity in the Council may now be passed by QMV. These include certain social security matters, mutual recognition of criminal judgments, minimum rules concerning certain procedural safeguards and the definition of criminal offences and sanctions in certain particularly serious crossborder crimes. In all these fields other than mutual recognition, the Lisbon Treaty provides for a so-called “emergency brake” which can be invoked by a Member State which considers that a proposed measure will affect important aspects of its social security system or fundamental aspects of its criminal justice system. The Lisbon Treaty replaces the EC with the EU for all purposes. Controversially in some quarters it states that the EU has a legal 9 November 2009 2 European Regulatory Alert The legislative procedure will then be suspended so that an attempt may be made to resolve the differences in the Council. The politically sensitive areas of judicial cooperation in civil matters (essentially recognition and enforcement of judgments), border checks, asylum and immigration, originally subject to unanimity in the Council, had already largely moved to QMV in the Council before the Lisbon Treaty, sometimes with consultation of the European Parliament, sometimes with co-decision. The Lisbon Treaty confirms that measures in all these areas will be subject to the ordinary legislative procedure. The UK, however, has retained its previous derogations in these areas: it is entitled to exercise border controls as it sees fit and is not bound by EU measures in the field of border checks, asylum, immigration, judicial cooperation in civil and criminal matters or police cooperation unless it expressly opts in to a specific legislative instrument. National Parliaments The Lisbon Treaty gives an enhanced role to national parliaments. EU legislation normally originates with a proposal submitted by the Commission to the EU legislature, namely the European Parliament and the Council. The Lisbon Treaty requires the Commission to submit the draft at the same time to parliaments of the Member States. National parliaments may submit a “reasoned opinion” on whether the proposed legislation infringes the principle of subsidiarity, according to which the EU may act only if the objectives cannot be better achieved at Member State level. If more than one third (or one quarter if the proposed legislation is in the area of criminal law or police cooperation) of national parliaments object, the Commission must review the proposal. In addition, national parliaments have a separate right to bring an action before the ECJ to challenge legislation on the ground that it infringes the principle of subsidiarity. Anchorage Austin Beijing Berlin Boston Charlotte Chicago Dallas Dubai Fort Worth Frankfurt Harrisburg Hong Kong London Los Angeles Miami Newark New York Orange County Palo Alto Paris Pittsburgh Portland Raleigh Research Triangle Park San Diego San Francisco Seattle Shanghai Singapore Spokane/Coeur d’Alene Taipei Washington, D.C. K&L Gates is a global law firm with lawyers in 33 offices located in North America, Europe, Asia and the Middle East, and represents numerous GLOBAL 500, FORTUNE 100, and FTSE 100 corporations, in addition to growth and middle market companies, entrepreneurs, capital market participants and public sector entities. For more information, visit www.klgates.com. K&L Gates comprises multiple affiliated partnerships: a limited liability partnership with the full name K&L Gates LLP qualified in Delaware and maintaining offices throughout the U.S., in Berlin and Frankfurt, Germany, in Beijing (K&L Gates LLP Beijing Representative Office), in Dubai, U.A.E., in Shanghai (K&L Gates LLP Shanghai Representative Office), and in Singapore (K&L Gates LLP Singapore Representative Office); a limited liability partnership (also named K&L Gates LLP) incorporated in England and maintaining offices in London and Paris; a Taiwan general partnership (K&L Gates) maintaining an office in Taipei; and a Hong Kong general partnership (K&L Gates, Solicitors) maintaining an office in Hong Kong. K&L Gates maintains appropriate registrations in the jurisdictions in which its offices are located. A list of the partners in each entity is available for inspection at any K&L Gates office. This publication is for informational purposes and does not contain or convey legal advice. The information herein should not be used or relied upon in regard to any particular facts or circumstances without first consulting a lawyer. ©2009 K&L Gates LLP. All Rights Reserved. 9 November 2009 3