L ife-CycleL earning, Earning, Incomeand W ealth

advertisement

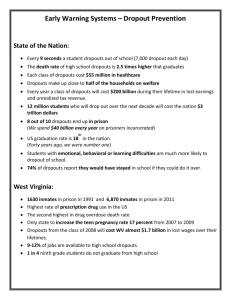

L ife-CycleL earning, Earning, Incomeand W ealth D avid A ndolfatto Simon FraserU niversity ChristopherFerrall Q ueen’s U niversity P aulG omme FederalR eserveB ankofCleveland N ovember2000 1 Introduction Individualswhoinvestheavilyinhumancapitaltendtoexperienceahigherlevel ofearnings andincomethroughoutmostoftheirlife-cycle. M ostoftheirhigher earnings arein theform ofhigherwages, butasigni…cantfraction is accounted forby a greaterwork e¤ort. In addition, such individuals tend to consume moreand accumulate…nancialassets atafasterrate. W hataccounts forthese di¤erences? W hile one mightbe inclined to attribute such di¤erences largely to luck, much ofthe heterogeneity we observe could also be due to personal choices thataremadeonthebasis ofan intrinsicsetoftastes andabilities that happen todi¤eracross people. O urpaperis aboutexploringtheplausibilityof this latterhypothesis. O neobvious measureofpasthuman capitalinvestments is thelevelofeducationalattainment. A mongadults in Canada and the U nited States, roughly 25% arehigh-schooldropouts, 50 % haveahigh-schooldiploma, and25% havea collegedegree. U nlikedemographicvariables such as age, sex, and race, educationalattainment(orhumancapitalaccumulationingeneral) is largelyachoice variable. Itseems reasonabletosuppose thatindividuals are from an early age generally aware ofthe bene…ts associated with higherlevels ofhuman capital investment;and yet, people clearly make di¤erentchoices. W hatdrives these di¤erentdecisions? O ne way tounderstand the human capitalchoice is in terms ofan optimal investmentdecision;seeB en-P orath (19 67). In theB en-P orath model, individuals seektomaximize the presentvalueoftheirlifetime earnings by allocating theirtime between work and learningactivities, and by choosingan appropriate expenditure path foreducationalgoods and services. A key parameterin this modelis the‘abilitytolearn’, modelledas thetechnologicale¢ciencywith 1 which learninge¤ortand resources augmentthe value ofhuman capital.1 N ot surprisingly, themodelpredicts thatmoreableindividuals choosetoundertake greaterhumancapitalinvestments, especiallyearlyoninthelife-cycle, andthat learninge¤ortdeclines overtime. D uring youth, less able individuals tend to earn more (as they devote more time towork ratherthan learning), butmore ableindividuals haverapidlyrisingearningpro…les thatsoon overtake thoseof thelessable. Inaddition, dispersioninearningsacrosseducationalgroupstends togrowovertime. T hese predictions are broadly consistentwith the evidence; e.g., seeL illard(19 7 7 ). W hilethebasicB en-P orath modelprovides aplausibleexplanation forwhy earnings pro…les mightdi¤er, before one can be con…dentthat ability di¤erences are at the root of inequality it would be prudent to examine whether the modelis consistentwith otherfacts, forexample, on laboursupply, consumption, and assetaccumulation behaviour. In orderto examine this issue, thebasicmodelmustbe extended toincorporate alabour-leisurechoiceand a consumption-savingdecision. Such an extension has been provided by B linder and W eiss (19 7 6 ), H eckman (19 7 6), and R yder, Sta¤ord and Stephan (19 7 6). Judging by whatis reported in the recentsurvey by N ealand R osen (19 9 8 ), these versions ofthe B en-P orath human capitalmodelrepresentthe extentto which this theoreticalset-up has currently progressed. B linderand W eiss (19 7 6) and R yder, Sta¤ord and Stephan (19 7 6 ) are primarily concerned with exploringwhatsortoflife-cycledynamics mightemerge in such an environmentfora ‘representative’individual.2 H eckman (19 7 6) reports theresults ofseveralcomparativedynamicsexercises, butdoes notalways provide a fulldescription ofjointbehaviour. Forexample, he …nds thatindividuals with greaterlearningability have peaks in theirhours ofwork pro…les atolderages, butwe are nottold howthese pro…les are positioned relative to each other. A s well, he does notask howdi¤erences in ability a¤ect…nancial assetaccumulation. T hepurposeofourpaperis explorewhatthis environmenthas tosayabout howlife-cyclepatternsofconsumption, learning, laboursupply, earnings, income andassetaccumulationshouldbeshapedas afunctionofparameters describing tastes and abilities. In this paper, we focus on three sources of parameter heterogeneity: (1) theabilitytolearn;(2) thesubjectiverateoftime-preference; and (3) thetasteforleisure. W ewish todiscover…rstofallwhetherany single source ofparameterheterogeneity mightbe able toaccountforthe qualitative di¤erences thatwe observe in the data. O urpreliminary …ndings suggestthat no single source ofparameterheterogeneity can accountforthe facts. N ext, we ask whetherthere are plausible combinations ofparameters thatmightbe able to explain the data. O urpreliminary …ndings suggestthatthe modelis broadly consistentwith the evidence ifwe assume thatpeople di¤erin their rate oftime-preference and theirtaste forleisure; and ifthese parameters are 1A notherwaytomodellearningability is in terms ofinitialendowments ofhuman capital. a very rich and complex setofdynamics is possible. 2 Evidently, 2 positivelycorrelated amongindividuals. 1.1 Some Facts In this section, we describe what‘typical’(median) life-cycle pro…les look like across threeeducationalgroups: dropouts;highschool;andcollege. T hedatais from theCanadian 19 9 2 FamilyExpenditureSurveyP ublicU seFile(FA M EX ) and is described in alittle more detailin A ppendix I. W e alsoreviewevidence from A ttanasio (19 9 4) who reports similarmeasurements from the 19 9 0 ConsumerExpenditureSurveyfortheU nited States. 1.2 Income, ConsumptionandSaving Figure 1 plots measures of after-tax income, consumption expenditures, and savingforeacheducationalgroup overtenperiodsofalife-cyclebeginningatage 21 andendingatage7 0. N otsurprisingly, morehighlyeducatedindividualshave signi…cantlymoreincomeateveryageexceptforveryearlyinthelife-cycle. T he age-income pro…le fordropouts displays a modesthump-shaped pattern, with incomepeakingage52 atalevelthatis 1 :65 times higherthan atage21. T he age-incomepro…leforcollegegraduates, ontheotherhand, displaysasigni…cant hump-shaped pattern, with income peaking atage 52 ata levelthatis 2:88 times higherthan atage21. A ccordingtothis data, collegegraduates generate roughlytwicetheincomeofdropouts aroundthepeakincomeyears. A ttanasio (19 9 4) reports similar …ndings for the U nited States. In particular, median income peaks in the 51–55 year-old cohort, with college graduates generating 2.84 times more incomethan dropouts. Q ualitatively, itappears thatconsumption tracks disposable income fairly closelyinthesenseofsharingthesamehump-shapedpattern. T hisfactthathas beenreferredtoasthe‘consumption-incomeparallel’(seeCarrollandSummers, 19 9 1) andis sometimes usedas anargumenttorejectthebasiclife-cyclemodel, which predicts a ‡atage-consumption pro…le. A ttanasioand B rowning(19 9 5) argue thatthe consumption-income parallellargely re‡ects family-size e¤ects. U sing several years of U .K. FES data to follow cohorts through time, they reproduce the …nding that consumption and income move togetherover the life-cycle. H owever, de‡atingconsumption byan adult-equivalentscale renders acompletely ‡atlife-cycle path foradjusted consumption. O n the otherhand, G ourinchas and P arker(19 9 9 ) arguethatwith theiradjustments, consumption continues todisplayahump-shape. T he bottom panel of Figure 1 displays household saving, de…ned here as thedi¤erencebetween householdafter-taxincomeandhouseholdconsumption. A ccordingto this measure ofsaving, the median household ofeach education group arenetsaversoverthelife-cycle(atleast, up toage7 0). H ighereducation groupstendtosavemore, bothintotalandasaratiooftheirdisposableincome. 3 In fact, the propensity to save remains fairly constantfrom age 32 onward in this data. O verthe entire life-cycle, saving rates average 8:8% fordropouts, 1 0 :6% forhighschoolgraduates, and 1 9:6% forcollegegraduates. T he FA M EX data setprovides a series called ‘netchange in assets’ which di¤ers (empirically, notconceptually) somewhat from the saving measure reported above. Q ualitatively, the net-change-in-assets series is similarin that highereducation groups tend to save more overthe entire life-cycle. B utaccordingtothis measure, themedian savingfordropouts is pretty close tozero overtheentire life-cycle and themedian savingforhighschoolgraduates is not very much larger. In addition, the levelofsavingbycollegegraduates is about halfofwhatis recorded by the earlierde…nition ofsaving. T he savingbehaviourreported in Figure 1 is broadly consistentwith SCF andP SID dataonwealthaccumulationpatterns across educationalgroups. A ccordingto Cagetti (19 9 9 ), median networth positions (includinghousingbut abstractingfrom pensionentitlements) areverylowandsimilaracross individualsatage30. W hileallthreeeducationalgroupstendtosaveovertheentirelifecycle, therateofassetaccumulation is much higherforwell-educatedindividuals. B yage6 0, themedian dropouthas accumulatedroughlybetween $60,000– 9 0,000;themedianhigh-schoolgraduatehasbetween$125,000–18 0,000;andthe median college graduate has between $250,000–300,000.3 In otherwords, to a …rstapproximation, each levelofeducation is associatedwith adoublingofnet worth in old age. 1.3 Earnings, L abourSupply and W ages Figure 2 plots measures ofearnings, laboursupply, and wages foreach educationalgroup overtenperiodsofalife-cyclebeginningatage21 andendingatage 7 0. A gain, itis notsurprisingtodiscoverthatbettereducatedindividuals tend tohave higherlife-cycle earnings. A ge-earningpro…les tend to display a more pronounced hump-shaped pattern relative to income, partly because earnings drop signi…cantly as peopleapproach old age. T henexttwopanels inFigure2 revealthatbettereducatedindividuals have higherearnings early on in the life-cycle because they allocate more time the marketsector;i.e., notbecausethe pecuniary return tolabouris higher. W age rates tendtogrowovertimeforalleducationgroups, butgrowmorequicklyfor the bettereducated. L aboursupply pro…les rise early on in the life-cycle and then ‡atten out, showinga modestdecline as the household ages;this pattern holds forall education groups. T he main di¤erence in labour supply across educationgroups is simplyinterms oflevels: collegegraduates workon average abouttwiceas hard adropouts. 3T he …gures are in 19 9 2 dollars. T he lower bound is from the S CF; the upper bound is from the P S ID . 4 1.3.1 T he R eturn on Education T here is a large empiricalliterature concerned with measuringthe ‘return’ to education;this literaturehas recentlybeensurveyedbyCard(19 9 8 ). T hestandard econometricmodeltaken tothe data is usually some variantofM incer’s (19 7 4) ‘human capitalearnings function’thatrelates somemeasureoflogearnings(logy)tosomemeasuresofeducationalattainment(S )andworkexperience (X );togetherwith astatisticalresidual(");e.g., logy = a+ bS + g(X )+ ": (1) A pparently, it is now conventional to refer to the estimated parameter b as the ‘return to education’. T ypically, the return to education is found to vary with certain characteristics ofindividuals, such as ‘ability’ and ‘family background’. Card argues thatthe empiricalspeci…cation above, with g modelled as athird orfourth degreepolynomial, provides areasonably good…twith the data, although, contrary to the speci…cation in (1), there does appearto be someevidence ofan interaction between education and experience. W hen log annualearnings are regressed on education and othercontrols, the estimated return to education is the sum ofthe bcoe¢cients forparallel models …ttothelogofwages (logw)andthelogofannualhours (logh):H ere, we reproduce Card’s (19 9 8 ) T able 1, which reports the estimated returns to education using(1) …ttothe19 9 4–9 6CP S. D ependentV ariable logw logh logy M en b R2 0.100 0.328 W omen b 0.109 R2 0.247 0.042 0.222 0.142 0.403 0.056 0.16 5 0.105 0.247 T hus, Card concludes thatin the U .S. labourmarketin the mid-19 9 0s, about two-thirds ofthe measured return to education in annualearnings data is attributable to the e¤ectofeducation on the wage rate, with the remainderattributabletothee¤ecton annualhours worked. 1.4 D ataSummary T hereadershouldkeep inmindthatthereareseveralpracticaland(unresolved) conceptualissues relating to the measurementofthese variables; see B rowning and L usardi (19 9 6 ) for details. B ut despite the quantitative di¤erences thatemerge dependingon howvariables are de…ned ormeasured, anumberof 5 qualitative features appeartobe robustacross di¤erentdatasets and di¤erent de…nitions/measurements. T heimportantqualitativedi¤erences areas follows: 1. Individuals ofa given age di¤erin terms ofaccumulated human capital (e.g., as measured byeducationalattainment). 2. Individuals whoinvestheavilyin human capital(bettereducatedindividuals) tend tohave higherincomes, earnings, consumption, and savings; (a) H igherearnings areattributabletobothhigherwagerates (2/3) and greaterworke¤ort(1/3); (b) H ighersavings attributabletohigherincomes and agreaterpropensity tosave. 3. T he dispersion in income, earnings, consumption, and savingacross educationalgroups peaks sometime in the middle ofthe life-cycle;the dispersioninlaboursupplyandsavingrates remains relativelyconstant;and the dispersion in wagerates is (weakly) increasingwith age. W e wish to focus on these qualitative features ofthe data and ask whethera sensibly parameterized life-cycle model(that endogenizes human capital and laboursupply) can accountforthesequalitativepatterns. 2 T he M odel Consideran economy populated by overlappinggenerations ofindividuals who liveforJperiods, indexedbyj = 1 ;2;:::;J:T hepopulation is assumedtogrow ataconstantratenperperiod, andwedenotetheshareofage-j individuals in thepopulation by ¹ j;which is time-invariantand satis…es ¹ j = (1 + n)¡1 ¹ j¡1 P forj = 2;:::;Jand J j=1 ¹ j = 1 : T hereis an issueas towhetheridiosyncraticrisks playan importantrolein the evolution oflife-cycle variables. O urfeeling on this matteris that, while idiosyncratic risks may be important, they are not dominant. T his view is supportedbytheempiricalworkofV enti andW ise(2000), whoinvestigatethe question ofwhy the dispersion ofwealth atretirementages is sogreat. T hese authors argue that90 % ofthe variation observed in retirementwealth is due tothe di¤erentchoices thatpeople make and nottoidiosyncraticluck. In the analysis below, we abstractfrom uncertainty. Individuals have preferences de…ned overdeterministictime-pro…les ofconsumption cj, leisure lj, as wellas a …nalnetworth position aJ+ 1 (bequeathed tothefuturegeneration);letpreferences berepresentedbytheutilityfunction: XJ ±j¡1 [U (cj)+ ¸V (lj)]+ ÂB (aJ+ 1 ): j=1 6 A ssumethatthefunctions U ;V andB areallstrictlyconcaveandthattheysatisfy standard Inadaconditions;wewilltreatthese functions as common across individuals. P references are parameterized by the discountfactor±;the taste forleisure¸;andthestrengthofthebequestmotiveÂ;individuals mayormay notdi¤eralong these dimensions. N ote: in this version ofthe paper, we set  =0 : T here are three uses fortime: marketwork n;learninge¤orte;and leisure l;where n+ e+ l= 1 (and theusualnon-negativityconstraints). L ethdenote human capital. P eoplemightdi¤erin theirinitialendowmentofhuman capital (onemeasureofdi¤erences in ability). A person’s human capitalis assumed to augmenttime-usein workingand learning;measured in ‘e¢ciency units’, work e¤ortequals hn and learninge¤ortequals he: Following H eckman (19 7 6), the human capitalaccumulation technology is given by:4 hj+ 1 = (1 ¡¾)hj + ®G (hjej); whereG is strictlyincreasingandconcave, ¾ is thedepreciation rateon human capital, and® isaparameterthatindexes‘learningability’. W ewillassumethat G and ¾ are common across households; however, ® may di¤er. L etv denote thevectorofparameters describingaparticularindividual;i.e. v = (®;±;¸): T here are twoprices in the model. L et! denote the price ofan e¢ciency unitoflaborand letR denotethe(gross) realrateofinterestpaid on …nancial assets. B oth ofthese prices willbe determined by marketclearingconditions in the generalequilibrium. N otethatlaborearnings are given by !hn;sothat w= !hcan beinterpreted as therealwage. Individuals can saveorborrowfreely atthegoinginterestrateR (thereare no debtconstraints beyond the end-period restriction aJ+ 1 ¸ 0 ). T he asset accumulation equation is given as follows: aj+ 1 = R aj + wjnj ¡cj; O ptimaldecision-making results in a desired pro…le fcj;nj;ej;lj;aj+ 1 ;hj+ 1 j !;R ;vgJ j=1 : W hatremains nowis thedeterminationofprices. Inasteady-state, theper capitacapitalstockis given by: K = (1 + n)¡1 XJ j=1 ¹j X aj(v)¤(v); v 4N otethatwearenotmodellingtheschoolingchoice perse. W hatwe are assumingis that individuals in the data who attend schoollongerare likely to investmore heavily in human capital atall stages ofthe life-cycle. T o the extentthat this is true, we can then associate people in the model with higher levels of human capital with people in the data who have highereducation. 7 where ¤(v)represents the fraction ofthe population with parametervectorv: T he percapitalevelofhours (measured in e¢ciency units) is given by: H= XJ ¹j X hj(v)nj(v)¤(v) v j=1 O utputis produced by aconstantreturns toscale production technology Q = F (K;H):Equilibrium prices aredetermined by theusualmarginalconditions: ! = F H(K;H) R = F K(K;H)+ 1 ¡Á; whereÁ is thedepreciationrateofphysicalcapital. Finally, goods-marketclearingrequires: C + (n+ Á)K = Q ; where, C = XJ j=1 2.1 ¹j X cj(v)¤(v): v P arameterization Functionalforms arerequired forU ;V ;G and F : U (c) V (z) G (x) F (K;H) = = = = (1 ¡° )¡1 [c1 ¡° ¡1 ] (1 ¡´)¡1 [z1 ¡´ ¡1 ] x³ KµH1 ¡µ: 3 Calibration A tthis stage, we do nothave the time to calibrate orestimate the modelas preciselyaswewouldlike. So, wewillcontentourselveswitharoughcalibration. W ecalibrate…rsttoa‘representative’individual;theparameters arechosen as follows. 3.1 D emographics L etthenumberofperiodsbeJ= 1 1 ;thelengthofaperiodis…veyears(thinkof peoplebeginningtheireconomiclifeatage20 andlivingto7 0). T hepopulation growth rateis setton= 0 ;sothat¹ j = 1 =Jforallj: 8 3.2 P references T he curvature parameteron U is chosen to be ° = 1 :5 (a standard choice). T he curvature forV is also chosen to be ´ = 1 :5: T he weighting factor for leisure is chosen tobe ¸ = 1 :752;this generates the resultthatroughly 1 =3 of available time is devoted to the labourmarket. T he discountfactoris chosen tobe ± = 0 :86;which implies an annualdiscountrate of3%: 3.3 Technology T helearningabilityparameteris setto® = 0 :40 ;this implies thatyoungpeople spend around 10% oftheiravailable time in learningactivities. T he curvature ofthe learningtechnology is taken from H eckman (19 7 6);³ = 0 :70 :T he share ofphysicalcapitalintotaloutputis settoµ = 0 :35:P hysicalcapitaldepreciates atan annualrate of1 2%;setÁ = 0 :48: A ssume thathuman capitaldoes not depreciate;¾ = 0 : 3.4 Endowments T he human capitalendowmentis normalized toh1 = 1 : 4 R epresentative Individual In Figure 3 we plot the life-cycle behaviourof the representative individual; i.e., the equilibrium based on theparameterization above. A s Figure 3 reveals, themodeldoes avery nicejob ofreplicating‘typical’life-cyclebehaviour, with the possible exception ofthe very aged. In particular, the modelpredicts that consumption continues torise throughoutthe life-cycle;the datasuggests otherwise. A s well, in themodel, individuals dissavein old agemuch morerapidly than in the data (we only plotthe …rst10 periods ofthe 13 period life-cycle). T his last feature could presumably be recti…ed by incorporating the bequest motive. 5 Single Sources ofH eterogeneity In this section, we shallconsiderthree separate sources ofheterogeneity and evaluate howeach, in isolation, is predicted toa¤ectlife-cycle behaviour. T he three parameters we considerare: (1) the ability tolearn, ®;(2) the discount factor, ±;and (3) the taste forleisure, ¸: Foreach case, we willmodelthree types, representinghigh, medium, and lowvalues, with 50 % ofthe population takingon the medium value, and the other50 % evenly divided across the two 9 extreme values. In equilibrium, each type ofperson willchoose adi¤erentlifetime learning pro…le; we label the group with the greatest life-time learning e¤ort‘collegegraduates’and thosewith thelowest‘dropouts’. 5.1 T he D i¤erent-A bility H ypothesis Supposethatindividualsdi¤eronlyintheirabilitytolearn;e.g., ® = 0 :32;0 :40 ;0 :48: T he results are plotted in Figure 4. N otsurprisingly, those with the highest learningability become‘college graduates’. O bservethattheearnings pro…les taketheexpectedshapein thesensethat those with low learning ability have higherearnings when young (relative to high learningability types), and relatively lowerearnings when old. T his basic qualitativepatternisalsohighlightedinN ealandR osen(19 9 8, Figure4.2), who remark thatthis U -shaped relationship between cohortearnings variance and cohortageis an importantthemein theliteratureon human capital. H owever, this U -shaped pattern is notpresentin ourdata, possibly because by age 21 (theyoungestageinoursample) wearealreadybeyondtheminimum dispersion point. A bility di¤erences seem to generate the right type of life-cycle wage patterns, butlaboursupplypro…les arequalitativelysimilaronlyafterperiod3 (age32).5 T hemostglaringde…ciencyin the“D i¤erent-A bilityH ypothesis” is whatit implies forassetaccumulation behaviour. A ccordingtothe model, individuals with low learning ability (dropouts) will accumulate …nancial assets rapidly, while those with high learningability (college) are predicted to hold negative net-worth positions formostoftheirlife. T he model’s logicis perfectly clear. W ealth takes twoforms in this model: human wealth and …nancialwealth. L owability individuals naturally wish to substitute intotheaccumulation of…nancialwealth, whilehigh ability individuals allocate theirresources toward accumulatinghuman capital. L ateron in thelife-cycle, thosewhoare rich in human capitalworkhardertoexploittheir relativelyhighskilllevels, whilethosewhoarerichin…nancialwealthcana¤ord toconsume moreleisure. 5.2 T he D i¤erent-D iscount-R ate H ypothesis T he idea thatpeople di¤erin theirdegree of‘patience’, and thatthis might explain much ofthe heterogeneity observed in economic behaviour, is an old one (e.g., see R ae, 18 34). H ere, we consider three rates of time-preference (annualized) equal to: 0 :0 275;0 :0 30 ; and 0 :0 325;the results are displayed in Figure5. 5 M easured hours of work here is totalhours worked plus time spentlearning, exceptfor those aged 21 and in college. T he idea here is thattraining is undertaken while on the job. 10 In a model without leisure, di¤erent discount rates would have no e¤ect on the levelofhuman capitalinvestment(assuming perfectcapitalmarkets). H owever, when leisure is endogenous and when personaltime is a necessary inputtolearning, di¤erencesinthesubjectiverateoftime-preferencewillinduce di¤erent levels of learning e¤ort. B ecause learning is a form of investment, one might naturally expect that relatively patient individuals would end up accumulatingmore human capital. Somewhatsurprisingly, the modelpredicts thattheleastpatientindividuals willaccumulatethe mosthuman capital;i.e., impatience here is positively correlated with the levelofeducation, although thedi¤erences in time devoted tolearningaresmall. O nepossible explanation forthis resultmightlie in the factthathuman capitalcannotbe consumed or sold as death approaches, unlike …nancialcapital. Consequently, more patient individuals (whowhenyoungplaceagreaterweightonend-of-lifeconsumption) mightpreferto accumulate wealth through a vehicle thatis bettersuited to providingforoldageconsumption. Inaddition, themorepatientplaceagreater weighton future leisure; and …nancialassetaccumulation ratherthan human capitalcan betterprovide forfuture leisure. In the model, patientindividuals (associated here with dropouts) preferto postponeconsumptionandleisuretoalaterage;hence, theyconsumelittleand workhardwhen young, sothatnetworth grows rapidly(although theyremain relatively unskilled). A ccordingtothe model, the reason why laboursupply is relatively lowfordropouts in latterstages ofthe life-cycle is because they are sowealthy. N eedless tosay, themodel’s explanation hardlyseems plausible. 5.3 T he D i¤erent-Taste-for-L eisure H ypothesis Suppose nowthatpeople di¤eronly in the relative weightthey place on consumptionandleisureatanypointin time;here, weconsiderthefollowingthree values forthe leisure parameter: ¸ = 1 :54; 1 :74; and 1 :94: A ccording to the model, those whoplace relatively lowweighton leisure arethe ones whoaccumulate morehuman capital. O utofthe three hypotheses considered sofar, the taste-for-leisure hypothesis seems to hold the mostpromise. In particular, the pro…les forearnings, hours worked and realwages are qualitativelysimilartoobservation. B utonce again, themostglaringde…ciencyofthis hypothesis is whatitpredicts forasset accumulationbehaviour: lowereducationgroups displayagreaterpropensityto save. A pparently, thosewhodonot…ndworkorschoolinge¤ortsopainfulprefertoaccumulatewealth through human capital, ratherthan through …nancial assets. 11 6 M ultiple Sources ofH eterogeneity T he main source oftension in the modelis thatwhich seems toexistbetween humancapitaland…nancialcapital;i.e., thesetwoforms ofcapitalrepresentalternativemechanisms bywhichtoaccumulatepurchasingpower. Consequently, ifoneis relativelygoodataccumulatinghumancapital(whetheritis becauseof higherability, less patience, oragreatertasteforconsumption), then onetends tosubstituteintohumancapitalattheexpenseof…nancialcapital. Inthedata, however, the propensity to accumulate human capitalis positively correlated with thepropensity toaccumulate…nancialassets. T heonlywaytogeneratethis positivecorrelationbetweenhumanand…nancialcapitalinvestmentis toconsidermultiple sources ofheterogeneity. In this section, weconsidertwoeconomies: onein which peopledi¤erin theirlearning ability and theirdiscountrate;and onein which peopledi¤erin theirtastefor leisure and theirdiscountrate. Forsimplicity, we assume aperfectcorrelation between thetwoparameters (sothattherewillcontinuetobeonlythree types ofindividuals). 6 .1 L earningA bilityand D iscountR ate A ssume thatpeople di¤erboth in theirability to learn and in theirdiscount rate;and thatthe discountrate (discountfactor) is negatively (positively) related with learningability. T hethree types ofindividuals are described by the followingparametercon…guration: T ype1 T ype2 T ype3 ® 0.30 0.40 0.50 ± 0.84 0.86 0.88 In the model, individuals who have a high ability tolearn and a lowdiscount rate(T ype3 individuals) end up accumulatinggreaterlevels ofhuman capital. T hehopehereis thatthehigh learningabilitywillresultinhigh humancapital investments and thatthe lowdiscountrate willresultin ahigh rate ofsaving. T he results are displayed in Figure 7 . A s the …gure reveals, this hypothesis holds some promise. H owever, high-ability people stilltend to be netdebtors earlyoninthelife-cycle(theywishto…nancetheirhumancapitalinvestments). Increasingthedispersion in the time-preferenceparametermay help alongthis margin;however, doingsowouldexacerbatethetiltsintheconsumptionpro…les (somethingwedonotsee in the data). 6 .2 Taste forL eisure and D iscountR ate A ssume nowthatpeople di¤erin theirtaste forleisure and in theirdiscount rate;andthatdiscountingispositivelyrelatedtothetasteforleisure. T hethree 12 types ofindividuals aredescribedby the followingparametercon…guration: T ype1 T ype2 T ype3 ¸ 1.25 1.7 5 2.25 ± 0.88 0.86 0.84 Inthemodel, individuals whohavealowtasteforleisureandalowdiscount rate(highdiscountfactor) endup accumulatinggreaterlevels ofhumancapital. A swiththeearlierexperiment, thehopehereisthatthelowtasteforleisurewill resultin high levels ofhuman capitalinvestments while the lowdiscountrate willresultin ahigh rateofsaving. Figure 8 demonstrates thatthis hypothesis has a great deal of promise; this …gure …ts the data better than any of the explanations proposed sofar. T heimplications ofthis hypothesis arepotentiallyprofound. Itargues that, while peoplemay appeartodi¤erin theirabilitytolearn, this di¤erencearises notfrom intrinsicdi¤erencesinlearningability(®);butfrom thehumancapital investments thatpeople have chosen tomake in the past(rememberthatitis thee¢ciencyunitoflearninge¤orthethatenters intothelearningproduction function). A bility here is to be interpreted as the manifestation ofhard work and frugal(forward-looking) tendencies. 7 D iscussion W ebelieve thatitis interestingtodiscoverwhatsortofintrinsicdi¤erences in peoplemightcausethem tomakeverydi¤erenteconomicdecisions. Knowledge oftheintrinsicstructureofheterogeneity(i.e., thedistribution ofdeep parametervalues) canplayanimportantroleinthedesignofsocialpolicy. Forexample, ifheterogeneous discountingis found to be important, then any redistributive policy should likely includeprovisions tomakeentitlements legally inalienable; seeA ndolfatto(2000). Ifitis foundthatthetasteforleisurematters morethan the ability to learn in explaining the data, then we can conclude thatpeople di¤erin theirskills notbecause ofintrinsic ability di¤erences butbecause of howtheychosetoallocatetheirtimein the past. Ifmitigatingskilldi¤erences (earnings di¤erentials) is a policy goal, then such a resultmightpointtoeducation subsidies. O n the otherhand, ifobserved heterogeneity is attributable to di¤erences in endowments (…nancialbequests orinitialhuman capitallevels), then lump-sum transfers may be the suitable instrumentto implementa redistribution policy. 13 FIGURE 1 Canada 1992 FAMEX Data Household After-Tax Income 70000 60000 50000 40000 30000 Dropouts Highschool College 20000 10000 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 Household Consumption 50000 40000 30000 20000 Dropouts Highschool College 10000 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Household Saving (After-Tax Income Minus Consumption Expenditure) 25000 Dropouts Highschool College 20000 15000 10000 5000 0 -5000 1 2 3 4 5 6 Age (21-70 Years) 14 7 8 9 10 FIGURE 2 Canada 1992 FAMEX Data Earnings 80000 60000 40000 20000 Dropouts Highschool College 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Full Time Equivalent Weeks Worked per Worker 60 50 40 30 20 Dropouts High School College 10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 Wage Rate (Earnings Divided by Hours) 40 30 20 10 Dropouts Highschool College 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 15 Age (21-70 Years) FIGURE 3 Representative Agent 0.24 0.45 0.22 0.40 0.20 0.35 0.18 0.30 0.16 0.25 Income Earnings Consumption 0.14 0.12 Work Work+Training 0.20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 0.25 0.56 0.20 0.52 0.15 0.48 0.10 0.44 0.05 0.40 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Wage Rate Net Worth 0.00 0.36 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 16 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 FIGURE 4 Differences in Learning Ability Earnings Income 30 30 Dropouts Highschool College 25 Dropouts Highschool College 25 20 20 15 15 10 10 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 Consumption 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 7 8 9 10 7 8 9 10 Measured Hours of Work 28 0.50 Dropouts Highschool College 26 24 0.45 0.40 22 0.35 20 0.30 18 0.25 16 0.20 14 Dropouts Highschool College 0.15 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 Net Worth 5 6 Wage Rate 40 70 Dropouts Highschool College 30 Dropouts Highschool College 60 20 50 10 40 0 -10 30 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 17 2 3 4 5 6 FIGURE 5 Differences in Time-Preference Income Earnings 24 22 20 22 18 20 16 14 18 12 Dropouts Highschool College 16 Dropouts Highschool College 10 8 14 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 Measured Hours of Work Consumption 26 0.50 24 0.45 0.40 22 0.35 20 0.30 18 0.25 Dropouts Highschool College 16 Dropouts Highschool College 0.20 14 0.15 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 Net Worth 5 6 7 Wage Rate 40 60 Dropouts Highschool College 30 55 20 50 10 45 0 40 -10 Dropouts Highschool College 35 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 18 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 FIGURE 7 Negative Correlation Between the Rate of Time-Preference and the Ability to Learn Earnings Income 0.32 0.26 Dropouts Highschool College 0.28 Dropouts Highschool College 0.24 0.22 0.24 0.20 0.18 0.20 0.16 0.16 0.14 0.12 0.12 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 Consumption 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 7 8 9 10 7 8 9 10 Measured Hours of Work 0.32 0.50 Dropouts Highschool College 0.28 0.45 0.40 0.24 0.35 0.20 0.30 0.16 Dropouts Highschool College 0.25 0.12 0.20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 Net Worth 5 6 Wage Rate 0.3 0.70 Dropouts Highschool College 0.2 Dropouts Highschool College 0.65 0.60 0.55 0.1 0.50 0.45 0.0 0.40 -0.1 0.35 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 19 2 3 4 5 6 FIGURE 6 Differences in the Taste for Leisure Income Earnings 28 26 26 24 24 22 22 20 20 18 18 16 16 14 Dropouts Highschool College 12 14 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 Dropouts Highschool College Measured Hours of Work Consumption 28 0.50 26 0.45 24 0.40 22 20 0.35 18 0.30 16 Dropouts Highschool College 14 Dropouts Highschool College 0.25 0.20 12 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 Net Worth 5 6 7 Wage Rate 40 65 Dropouts Highschool College 30 60 55 20 50 10 45 0 Dropouts Highschool College 40 -10 35 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 Figure 1: 20 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 FIGURE 8 Positive Correlation Between the Rate of Time-Preference and the Taste for Leisure Earnings Income 0.35 0.28 Dropouts Highschool College 0.30 Dropouts Highschool College 0.26 0.24 0.22 0.25 0.20 0.20 0.18 0.16 0.15 0.14 0.10 0.12 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 Measured Hours of Work Consumption 0.35 0.55 Dropouts Highschool College 0.30 0.50 0.45 0.25 0.40 0.35 0.20 0.30 0.15 Dropouts Highschool College 0.25 0.10 0.20 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 Net Worth 5 6 7 Wage Rate 0.4 0.60 Dropouts Highschool College 0.3 0.55 0.2 0.50 0.1 0.45 0.0 0.40 -0.1 Dropouts Highschool College 0.35 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 21 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 A ppendixI: D ataD escription T he data come from the 19 9 2 Family Expenditure Survey P ublic U se File (FA M EX ). W eselectedthosehouseholds withnomorethan 2 wageearners and with thereferenceperson reportingsomeeducation. A llstatistics areweighted by theFA M EX weightvariable. H ouseholds were grouped into…ve-yearage categories and three education categories. M arried households were grouped accordingto the greaterlevelof education and age ofthe spouses. T hatis, the age category ofthe household is the maximum ofthe two spouses ages, and the education category is the maximum ofthe two spouses education levels. T he education categories, as dictated in partby the publicuse …le, are less than a high-schooldegree, high schooldegreeand somecollege oruniversity, and auniversitydegree ormore. T heFA M EX contains avariableequaltothetotalnumberofperson-weeks within the household takingintoaccountthe exitand entry ofpersons during the year. Consumption and expenditure are converted to “perperson-week” units usingthis variable. T he documentation forthe Family Expenditure Survey 19 9 2 can be found at: http://130.15.16 1.7 4/webdoc/ssdc/cdbksnew/famex/famex9 2guide.txt 22 R eferences 1. A ndolfatto, D avid (2000). “A T heory ofInalienable P roperty R ights,” M anuscript: U niversityofW aterloo. 2. A ttanasio, O razio P. (19 9 4). “P ersonal Saving in the U nited States,” in InternationalComparisons ofH ousehold Saving, edited by James M . P oterba, N ationalB ureauofEconomicR esearch, T heU niversityofChicago P ress. 3. A ttanasio, O razio P. and M artin B rowning (19 9 5). “Consumption over theL ifeCycleandovertheB usiness Cycle,” A merican EconomicR eview, 8 5(5): 118 7 –1237 . 4. B lackorby, CharlesandD avidD onaldson(19 8 8 ). “CashV ersusKind, SelfSelection, and E¢cient T ransfers,” A merican Economic R eview, 7 8 (4): 6 9 1–7 00. 5. B linder, A lan S. (19 7 4). T owardan EconomicT heoryofIncome D istribution, T heM IT P ress. 6 . B linder, A lan S. and Y oram W eiss (19 7 6 ). “H uman Capitaland L abor Supply: A Synthesis,” JournalofP oliticalEconomy, 8 4(3): 449 –47 2. 7 . B rowning, M artin and A nnamaria L usardi (19 9 6). “H ousehold Saving: M icroT heoriesandM icroFacts, JournalofEconomicL iterature, X X X IV (4): 17 9 7 –1855. 8 . Cagetti, M arco (19 9 9 ). “W ealth A ccumulation O verthe L ife Cycle and P recautionarySavings,” M anuscriptpresentedatthe19 9 9 N B ER Summer Institute. 9 . Card, D avid(19 9 8 ). “T heCausalE¤ectofEducationonEarnings,” forthcomingin theH andbookofL aborEconomics. 10. Carroll, ChristopherD . and L awrence H . Summers (19 9 1). “Consumption G rowth P arallels IncomeG rowth: SomeN ewEvidence,” in N ational Savingand Economic P erformance, edited by B . D ouglas B ernheim and John B . Shoven, N ationalB ureau ofEconomicR esearch, T he U niversity ofChicagoP ress. 11. G ourinchas, P ierre-O livierandJonathanA .P arker(19 9 9 ). “Consumption O verthe L ife Cycle,” M anuscriptpresented atthe 19 9 9 N B ER Summer Institute. 12. H eckman, James J. (19 7 6). “A L ife-Cycle M odelofEarnings, L earning, and Consumption, JournalofP oliticalEconomy, 8 4(4) P art2: S11–S39 . 13. L illard, L eeA . (19 7 7 ). “Inequality: Earnings vs. H uman W ealth,” A merican EconomicR eview, 67: 42–53. 23 14. M incer, Jacob (19 7 4). Schooling, Experience and Earnings, Columbia U niversity P ress. 15. N eal, D erek and Sherwin R osen (19 9 8 ). “T heories ofthe D istribution of L aborEarnings,” N B ER workingpaper637 8: www.nber.org/papers/w637 8 . 16 . R ae, John(1834). StatementofSomeN ewP rinciplesontheSubjectonthe SubjectofP oliticalEconomy, B oston: H illiard, G ray and Co., reprinted by A ugustus M . Kelley, B ookseller, N ewY ork(19 64). 17 . R yder, H arlE., Sta¤ord, Frank P. and P aula E. Stephan (19 7 6). “L abor, L eisure and T rainingO verthe L ife Cycle,” InternationalEconomic R eview, 17 (3): 6 51–6 7 4. 18 . V enti, StevenF. andD avidA . W ise(2000). “Choice, Chance, andW ealth D ispersion atR etirement,” N B ER workingpaperno. 7 521. 24