Review of the Balance of Competences between the United Kingdom and the

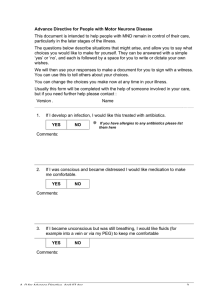

advertisement