Challenges to building a safe and secure Information Society

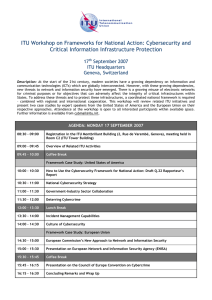

advertisement