I C S

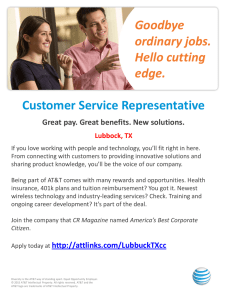

advertisement