Irony and metarepresentation ∗∗∗∗ DEIRDRE WILSON

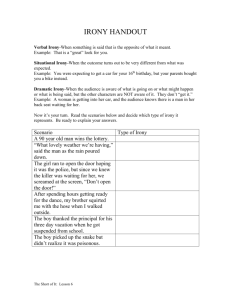

advertisement