Singular Content and Deferred Uses of Indexicals* THIAGO N GALERY

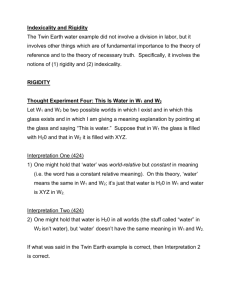

advertisement