Interpreting IDensification Harris Constantinou

advertisement

UCLWPL 2011.01

81

Interpreting IDensification

Harris Constantinou

Abstract

We put forward a new theory aiming to account for the interpretation of the English intensifier (i.e.

himself as in John himself met Mary). We show that its interpretation is regulated by the interplay

between information structure, semantics and surrounding context. More concretely, we propose (a)

that the intensifier can assume any role of the component of information structure, which we assume to

consist of the autonomous notions of [contrast], [topic] and [focus] (Neeleman and van de Koot 2008,

Neeleman and Vermeulen 2010); (b) that the intensifier always denotes an identity function (ID)

which takes a nominal constituent x as its argument and maps it onto itself (Eckardt 2001, Hole 2002,

Gast 2006). and (c) that specific contextual (both sentential and pragmatic) factors can influence its

interpretation. The theory assumes only one lexical entry for the intensifier and derives its properties

through independently motivated assumptions, thus claiming superiority at least over polysemous

analyses (i.e. Edmondson and Plank 1978, König 1991, Siemund 2000, Eckardt 2001). This proposal

also undermines accounts that assume one lexical entry but derive each use of the intensifier from its

structural position (i.e. Gast 2006).

Keywords: intensifier, contrast, topic, focus

1. Introduction

Examples (1) - (3) constitute a minimal triplet differing only with regard to the position of the

intensifier. In (1) himself is found immediately next to a nominal constituent and this sentence is

roughly understood as the king (in person), and not someone else, performs the action described

by the predicate. We will be referring to this instance of the intensifier as the in person reading.

In (2) himself is found immediately after the auxiliary verb and the example can be paraphrased

with also or too (König and Siemund 1999) (henceforth called the also reading). In (3) himself is

found in a sentence final position, giving rise to a paraphrase containing alone or without help

(König and Siemund 1999) (henceforth called the alone reading). Note that these approximate

paraphrases are merely used throughout most of this paper for the purposes of exposition and avoidance

of any confusion between the many readings of the intensifier. They have no theoretical significance.

(1)

(2)

(3)

The king himself has come to the meeting (and not his secretary).

(Apart from the king‘s secretary,) The king has himself come to the meeting.

The king has come to the meeting himself (without anyone accompanying him).

As shown in the examples above, the intensifier is never found in an A-position and hence does

not receive a θ-role. Therefore, syntactically it is a modifier (or adjunct). Furthermore, it is

always understood to interact with a nominal constituent, even if they are not found next to each

other. In the case of (1) - (3), this nominal constituent is the subject with which the intensifier

I gratefully acknowledge the Leventis foundation and AHRC (UK) for their valuable financial support. I

would also like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Hans van de Koot for his advice and numerous comments on earlier

drafts of this paper.

UCLWPL 2011.01

82

agrees in person, number and gender1. Despite the apparent interpretational dissimilarity of the

examples above, which has led to analyses based on diametrically opposed assumptions, most

researchers agree on one point: an intensifier evokes alternatives to the referent of the nominal

constituent it interacts with and compares this referent with these alternatives. Combined with

the fact that the intensifier is universally stressed and carries some sort of accentual prominence

within the sentence, many analyses (Eckardt 2001, Hole 2002, Gast 2006, among others) suggest

that the inducing of alternatives arises from its interaction with the focus structure of the

sentence (Rooth 1985, 1992).

We think that the above view is on the right track. However, we believe that it has not been

explored in sufficient detail, precisely because previous researchers have underestimated the role

of information structure in their attempts to explain the phenomenon under discussion. This

paper advocates that the properties of the intensifier can be further elucidated if we accord a

more central role to information structure. The main thesis to be defended is that the intensifier is

effectively an information structural device, in the sense that its interpretation is governed by the

interpretative contribution of contrast, topic or focus, or a possible combination of them2. These

notions comprise a particular component of information structure as described by Neeleman and

Vermeulen (2010)3. This hypothesis is flexible enough to derive all the readings that have been

observed. For example, we propose that the alone use of the intensifier is an instance of

contrastive focus whereas the so-called as for use (see example (15) is an instance of contrastive

topic. Their interpretational difference is primarily a result of the semantics associated with these

two information structural notions.

1

This type of φ-feature specification is by no means universal. For instance, the Dutch intensifier is not

specified with any φ-features. Thus the sentence in (a) is ambiguous between the two readings in (b-c).

a.

Jan

heeft

Marie

zelf

een kado

gegeven.

John

has

Mary

x-self

a present

given.

b.

John

himself

has

given

Mary

a present.

c.

John

has

given

Mary

herself

a present.

2

This generalization becomes clearer later in this paper, when we discuss how the intensifier is semantically

specified. In a nutshell, we argue that its lexical entry is specified with ID, a truth-conditionally meaningless

function that maps its satisfier onto itself. Naturally, this exceptionally basic semantic specification leaves room for

an information-structure oriented approach.

3

We are not the first to follow this line of reasoning. In the same spirit, Féry (2010) proposes that the German

intensifier selbst can be an instance of a free focus. However, her account remains largely inconclusive with regard

to the relatively free interpretation of the intensifier. Also, her account diverges from ours with respect to the reasons

found behind the uses of intensifiers. She claims that the different interpretations are a result of the different

domains of the free focus intensifier. These domains are determined by the structural position of the intensifier. By

contrast, we argue that the intensifier’s interpretation is not determined by its structural position and that its different

uses are primarily a result of their characterisation as a contrastive topic, contrastive focus, topic or focus. Bergeton

(2004) also pursues a line of research similar to Féry’s by suggesting a focus-based analysis. He distinguishes four

readings of the intensifier, namely the three shown in (1) - (3) plus a reading paraphrasable to even. Apart from the

fact that he does not account for all the readings that the intensifier can exhibit, he assumes a different approach to

derive the readings, one that is too strict, we believe, to account for all available interpretations. Due to lack of

space, we do not outline Bergeton’s approach.

UCLWPL 2011.01

83

Section 2 surveys some previous analyses and paves the way for our proposal. Our purpose

is not to offer a full review of these accounts, or by any means of the abundant literature around

the topic, but simply to expose some of the fundamental problems of certain assumptions that

persist throughout the literature and introduce some of the notions that will be required for our

analysis. Section 3 develops the core proposal of this paper, and derives the various

interpretations of the intensifier. Section 4 concludes the discussion.

2. Some remarks on previous accounts

2.1. Previous accounts

On the face of it, examples such as (1) - (3) suggest that one could try to link the interpretation of

an intensifier to its position in the sentence. According to prior literature on the topic there are

two ways in which one could go about doing this. One possibility is to assume that every

interpretation of the intensifier is listed separately in the lexicon and that each lexical realisation

is compatible with only a certain position within the sentence. Alternatively, one could assume

that there is only a single lexical entry with a fixed base-generated position. Its various surface

positions would then be derived through movement. On this second approach, the difference in

interpretation associated with each position is attributed to a variety of contextual (syntactic,

semantic, or pragmatic) reasons4. Edmondson and Plank (1978) follow the former line of

reasoning and distinguish intensifiers in terms of their position. In their terminology, himself1 is

always attached to the nominal phrase it modifies (as in (1)). The function of himself1 is to place

the referent of the nominal it modifies in the highest position on a scale of remarkability. In other

words, this instance of the intensifier marks the referent it interacts with as the least expected

person/thing in the situation described by the sentence. On the other hand, himself2 is never found

attached to the nominal it interacts with but still orders its referent with regard to a scale. In this

case, however, the scale is defined in terms of direct involvement by characterising the referent

of the intensified DP as the value most directly involved in the situation. As Cohen (1999) points

out, even though the notions of remarkability and direct involvement are suggested to constitute

a central component of the meaning of himself1 and himself2 respectively, they do not shed any

light on the intensifier‘s function. Examples (4) - (5), taken from Cohen (1999), show that these

notions are irrelevant to the semantic contribution of the intensifier.

(4)

The staircase wound round the lift shaft and went the whole way to the roof, though the lift

itself went no further than the top floor. (Sayers 1986: p.51)

My grandmother knows these things. She is a witch herself.

(5)

4

As mentioned in the introduction, we do not intend to offer a complete literature review of previous

proposals, but simply to briefly consider a few representatives of each line of reasoning. This is both for reasons of

space and because the arguments presented here apply to all proposals which assume an absolute correlation

between the position and interpretation of the intensifier, whether through a polysemous analysis (Moravcsik 1972,

Dirven 1973, Edmondson and Plank 1978, König 1991, König and Siemund 1999, Siemund 2000,) or a

monosemous one (see Gast 2006 for a movement approach, Primus 1992 for an analysis attributing the various

interpretations to the nature of the constituent the intensifier attaches to). For an extensive literature review and

criticism of the proposals outlined here see Cohen (1999), Eckardt (2001), Siemund (2000), Gast (2006), Tavano

(2006).

UCLWPL 2011.01

84

In (4), the lift, despite being modified by himself1, is not understood as being ordered in a scale

of remarkability or even as being remarkable at all. A similar problem is raised by (5), an

instance of himself2, in which my grandmother is not understood as being more directly involved

in being characterised as a witch compared to the rest of the people who are witches. König

(1991, 2001), König and Siemund (1999) and Siemund (2000)5 also follow the first line of

reasoning and (at least) draw a clear link between focus particles such as also, only, and too and

the intensifier. They distinguish three different intensifiers, namely the adnominal (in person

reading), the adverbial inclusive (also reading), and the adverbial exclusive (alone reading).

What seems to be the underlying connection between these three lexical entries is the notion of

centrality (see Baker 1995 for a similar notion, namely of discourse prominence). According to

König and Siemund, all intensifiers characterise the referent of the DP they interact with as

‗central‘, and oppose it to a set of alternative values which are ‗peripheral‘ to the head DP. For

example, the king in (1) - (3) is not compared with just any alternative but only with ones that are

peripheral to the king, such as the king‘s family or the king‘s staff. Apart from their

interpretational variation (as described in the first paragraph of the present paper), what

distinguishes the adverbial types from the adnominal is their distribution. As its name indicates,

the adnominal intensifier is assumed to be a nominal modifier, hence is usually found next to an

NP, whereas the adverbial intensifiers are assumed to be verbal modifiers, hence occurring

somewhere in the VP domain. The main argument, however, in favour of the view that the three

uses of the intensifier are a clear case of polysemy is the ability to build grammatical (laboratory)

sentences exhibiting all the uses simultaneously, as the example below of Siemund (2000)

shows.

(6)

Bill himself has himself not found the answer himself.

However, Gast (2006) shows that the above example does not necessarily illustrate the

polysemous nature of the intensifier. He follows König and Siemund with regard to the possible

interpretations that the intensifier can have (i.e. exclusive adverbial, inclusive adverbial,

adnominal), assuming though a single lexical entry, whose denotation is the identity function ID

that takes a nominal constituent x as its argument and maps it onto itself. This minimal semantics

combined with the assumption that the intensifier always interacts with the focus structure of the

sentence derives some of its interpretational properties (such as the evoking of alternatives). In

particular, he assumes that the intensifier is always base-generated in a position attached to the

DP it modifies. Its various positions are accounted for by assuming that the complex of DP and

associated intensifier undergoes several steps of movement and may strand the intensifier at any

point in the course of the derivation. This is illustrated in (7) for the exclusive interpretation.

(7)

I1 always [TP t1 [do my homework]2 [vP [DP t1 myself] t2 ]].

In this example the following operations are assumed to take place: i) do is moved to T0, ii) the

complement my homework is pied-piped to satisfy the phonological constraint FINALFOCUS

(see Larson 1988 for an analysis of pied-piping that fits this proposal and Büring 2001 for

discussion of FINALFOCUS) iii) the subject DP associated with the intensifier, I, initially moves

5

For an extended criticism of this approach see the works themselves in which the authors recognise that their

analysis faces some serious problems mostly related to the parallelism with focus particles (König 1991, König and

Siemund 1999, Siemund 2000, König 2001) or Eckardt (2001), Bergeton (2004), Gast (2006).

UCLWPL 2011.01

85

to [Spec,TP] and then to [Spec,FinP]6. As is evident from the derivation, the movement of

material across the intensifier is licensed by the FINALFOCUS constraint (the subsequent

movement operation is assumed to result from [Spec,FinP] attracting the subject). However,

when it comes to the inclusive intensifier, which, according to Gast, can occur either in postauxiliary position or sentence-finally, the same phonological constraint is suspiciously less

stringent7. Regarding the interpretational differences between the adnominal and the two

adverbial instances of the intensifier, Gast suggests that they result from their structural position,

which in turn forces them to interact with different types of constituents. Whereas the adnominal

only interacts with a DP, the two adverbials interact with the entire predication. The

interpretational difference between the two adverbial instances is the outcome of the assumption

that the inclusive use is structurally located outside the VP, whereas the exclusive use is located

within the VP. This assumption is based on the argument that the exclusive use is invariably

within the scope of negation, whereas the inclusive one is always outside the scope of negation

(but see Eckardt 2001 for problems with this generalisation)8.

From a purely conceptual point of view, we find it implausible that the well-known crosslinguistic freedom in the distribution of intensifiers should follow from a conspiracy of

movement operations. In Gast‘s proposal, trying to do so comes at the price of associating each

positional variant of the intensifier with quite ad hoc assumptions about the movement triggers in

the sentences that contain them. What matters most here, however, is the fact that Gast ties

every meaning of the intensifier to a particular structural position, and as illustrated later in this

paper, such an approach accounts only for a fraction of the data.

2.2. One lexical entry, many structural positions (round 1)

The common characteristic of the accounts outlined so far is the fact that they assume a

correlation between the structural position of the intensifier and its interpretation. In other words,

they predict that an intensifier found attached to the nominal DP it interacts with cannot have the

same interpretation as one that is not adnominal. This prediction is immediately falsified by the

following examples, where the continuation and not his secretary ensures that the interpretation

of the intensifier remains stable across the board.

(8)

a. The director himself has appeared, and not his secretary.

b. The director has himself appeared, and not his secretary.

c. The director has appeared himself, and not his secretary.

Note that our informants have explicitly stated that the above examples do not differ in the

slightest either with regard to grammaticality or interpretation. Their interpretation is consistent

6

Note that these are not the only movement operations that Gast assumes. In order to derive the sentence final

inclusive intensifier in Swedish, he further assumes that the whole verb phrase moves across the intensifier to some

position above TP. This type of movement is widely known as “heavy shift”. The Swedish example below shows

this process (taken from Gast (2006: p. 91))

a)

...för att jag3 [t2 har levt i Oslo]1 [t3 själv]2 t1

. . because I have lived in Oslo myself

7

The same point is valid for the adnominal intensifier found next to the subject of the sentence, or for any

instance of the intensifier which is not sentence final (remember that intensifiers are always stressed).

8

Due to lack of space we do not offer a full review of Gast’s analysis.

UCLWPL 2011.01

86

with the widely adopted view that the intensifier evokes alternatives to the referent of the

intensified DP, whilst at the same time excluding them (what König 1991, Siemund 2000 and

Gast 2006, among others, call the adnominal meaning). In the case of (8a-c) the contrasting

alternative is the director’s secretary. What becomes apparent from (8a-c) is that the context, and

not the structural position of the intensifier, is the decisive factor for its interpretation. Note that

if it was the case that this intensifier meaning was intrinsically tied to the adnominal structural

position, the sentences (8b-c) should at least be rendered infelicitous due to the strong effect of

the surrounding context. Indeed, the linguistic context supplied in these examples should be

incompatible with the meaning of the intensifier. The examples below apply the same test to the

remaining two readings of the intensifier that we have encountered up to now (paraphrased as

also and alone/by x-self).

(9)

Context: Speaker A: Being poor is tough.

a. Speaker B: Yes, I know, I myself have been poor and I remember it wasn‘t easy.

b. Speaker B: Yes, I know, I have myself been poor and I remember it wasn‘t easy.

c. Speaker B: Yes, I know, I have been poor myself and I remember it wasn‘t easy.

(10)

Context: Speaker A: John found the way to the station with his brother.

a. Speaker B: ? No, no John himself has found the way to the station.

b. Speaker B: ? No, no John has himself found the way to the station.

c. Speaker B: No, no John has found the way to the station himself.

The examples in (9a-c) illustrate the same point as before but with the also reading of the

intensifier. This reading exhibits the same distributional flexibility found with the in person one.

The relative infelicity of (10a-b), however, is unexpected, given what we concluded with regard

to the other two readings of the intensifier. As evident from (10a-c), the alone reading of the

intensifier seems to prefer a post-verbal position. It cannot be the case that this position is tied to

this reading because we have already seen examples where a post-verbal intensifier does not

have the alone reading. Another idiosyncrasy of this reading is that it imposes restrictions on the

event-type of the predication it is found in. As König (1991) points out, this reading is present

only in sentences describing non-repeatable activities. Siemund (2000) elaborates on this idea

and suggests that the alone/by x-self reading is only compatible with verbs denoting

accomplishments or achievements (the examples in (10) all have interpretations compatible with

this claim). This is illustrated in the example provided by Gast (2006) in (11), which becomes

infelicitous if we attempt to interpret myself in this way (alone). This is due to the stative nature

of the verb to be.

(11) # I am a gardener myself.

In section 3 we argue that both the incompatibility of this reading with stative verbs and its

restriction to post-verbal positions is a consequence of the nature of the evoked alternatives. For

the time being, note that the wider context is a crucial factor in defining the interpretation of the

intensifier. The example below, which repeats (10c) but with a different context, is intended to

show that intra-sentential factors (i.e. type of predicate) do not have anything to do with the

choice of the reading. Hence, this time the preferred reading is the also one.

(12) Speaker A: Bill managed to find the way to the station the other day, surprisingly!

UCLWPL 2011.01

87

Speaker B: Well, he is not the only one! John found the way to the station himself!

The overall discussion up to this point leads us to the conclusion that approaches which correlate

a particular interpretation of the intensifier with a syntactic position are far too restrictive.

Evaluating these accounts from a purely interpretational perspective illustrates the same

point; assuming two or three fixed readings for the intensifier is again far too restrictive. There is

an abundance of interpretations of the intensifier; Cohen (1999) provides us with the example in

(13), in which the intensifier has a reading closely paraphrasable to even (henceforth called the

even reading); a reading akin to the focus particle only is shown in (14) (henceforth called the

only reading), even though it is not perfectly felicitous (see section 3 for an explanation); finally,

a reading similar to the phrase as far as x is concerned (or as for x) (henceforth called the as for

reading) is illustrated in (15)9.

(13) Clinton himself will vote for the Republicans. (paraphrase: Even Clinton will ...)

(14) Speaker A: Mary gave Jane her syntax course-book and all the notes before leaving the

university. At least that what she told me!

Speaker B: ?Well, you must have misheard! Mary gave the syntax course-book itself, and

threw away the notes. (paraphrase: ... Mary gave John only the syntax ...)

(15) Speaker A: How was your first flight to the US? (Speaker B is afraid of flying)

Speaker B: Well, the flight itself was ok, but seriously... you don‘t want to know about the

landing! (paraphrase: Well, as for the flight, it was ok, ...)

Up to this point we have pin-pointed six readings of the intensifier, and there may well be others.

Our intention though is not simply to spell out a full list of the interpretations of the intensifier.

Instead, we attempt (in section 3) to provide a uniform treatment of intensifiers that assumes a

single lexical entry, while being flexible enough to accommodate and predict all the possible

readings of the intensifier.

2.3. One lexical entry, many structural positions (round 2)

Contrary to the empirical character of the arguments presented above, we now attempt to argue

for a common lexical entry for all the uses of the intensifier based on arguments of a more

conceptual basis, which in turn are based on empirical observations found in the literature. The

first argument is based on the (obvious) observation that the various readings of the intensifier

(i.e. himself) do not affect its morphological make-up. For researchers who assume a different

lexical entry for each of these readings, this amounts to the claim that a single word can have at

least six different lexical entries (these are the readings we detected up to this point). On top of

this, the same word serves the purpose of being a reflexive in English, thus adding one more

entry, leaving us with at least seven entries. Clearly, this is theoretically unattractive. Moreover,

to our knowledge, there is no other word in the language with so many lexical entries. Note that

9

The reading is most easily accessible with a B-accent, characteristic of contrastive topics (Jackendoff 1972),

maximally realised as L+H* and followed by a default low tone and a high boundary tone (L H%) on the intensifier.

Contrastive topic is indicated with double underlining throughout the rest of the paper.

UCLWPL 2011.01

88

the situation in English is not unique. Cross-linguistically, numerous languages10 encode all the

different readings of the intensifier with one word (i.e. Dutch: zelf, German: selbst, Greek: o

idios).

Moravcsik (1972), Siemund (2000), and Gast (2006), among others, argue that the

different uses of the intensifier impose dissimilar selectional restrictions on the nominal

constituent it interacts with. No consensus has been reached with regard to this issue. For

example, Siemund (2000) argues that the in person reading does not impose any restrictions on

its head-DP, thus it can denote anything (i.e. [±human])11, whereas the alone reading cannot

interact with DPs denoting anything other than humans and higher animals. The same author

suggests that the also reading can only interact with humans. On the other hand, Gast (2006)

counter-argues the above claims on the basis of examples such as (16) and (17).

(16) Any business that stores sufficiently large amounts of hazardous waste can be a storage

facility even if it is merely storing the waste that it produced itself on the site where it was

produced.

(17) We are works of art, belonging to a world that is itself an aesthetic phenomenon.

Examples (16) and (17) illustrate that no selectional restrictions on the associate DP in terms of

an animacy hierarchy are imposed by the alone and also readings, respectively. The example

below illustrates that the even reading does not impose any animacy-related selectional

restrictions on its associate DP either.

(18) Context: Two geologists are discussing the fact that Japan’s earthquake was so strong that

it was supposedly felt all over the world. It is shared knowledge between them that France

is the most distant country from Japan.

Japan‘s earthquake was massive! The whole world felt the shake. France itself felt the hit.

Examples (14) – (18) force us to conclude that the different readings of the intensifier do not

impose any restrictions with regard to the animacy status of their head-DP12. This common

property of all readings of the intensifier provides more support for an account assuming a single

lexical entry.

10

We have not been able to find a study that checks this parameter. We suspect from König and Siemund’s

cross-linguistic morphological comparison between intensifiers and reflexives (WALS, 27.3.2011) that most

languages encode the various readings of the intensifier in one word.

11

There is consensus for the in person reading’s absence of animacy-related restrictions. Irrespectively of this

point, we take it for granted that everyone agrees that all the readings can interact with human referents, and

therefore do not provide any examples of such uses.

12

Of course it is not expected that the intensifier will exhibit the same behavior with regard to animacy

restrictions on its associated DP universally. Gast (2009) discusses this issue and illustrates that in Japanese there is

one intensifier that can interact only with animate DPs, namely jishin, and one intensifier that can interact only with

inanimate DPs, namely jitai. As he explains, the reason for this discrepancy is associated with the historical origin of

each word. For example, jishin is lexically derived from the word body, hence its use is restricted to animate DPs

(things which have bodies). What we do expect however, is for one and the same morphological word not to have

different selectional restrictions across different readings.

UCLWPL 2011.01

89

Aside from the animacy restrictions just discussed, there has been no consensus in relation

to whether the intensifier can interact with indefinite DPs, and if so, on which readings.

Moravcsik (1972) provides the minimal pair example below aiming to illustrate that an in person

reading is not able to interact with indefinites, while an alone reading is.

(19) a. An engineer should know this himself.

b. ?An engineer himself should know this.

We believe that examples such as the above have misled various researchers towards accounting

for the wrong facts. Eckardt (2001), for example, takes this picture for granted and assumes a

different semantics for each variant (head-adjacent vs head-distant), particularly tailored to

express that the head-distant (or adverbial) occurrences can interact with indefinites whereas the

head-adjacent ones cannot. Following Siemund (2000), we would like to argue that, despite

appearances, all the readings are equally incapable of interacting with true indefinites. The word

true is meant to exclude indefinite DPs which have a generic or specific interpretation. As

pointed out by Siemund, the apparent ability of the alone reading to interact with indefinites is

owed to the fact that these DPs are invariably interpreted as generic or specific13. Indeed, (19a)

has a generic reading. (20) illustrates that despite its indefinite nature, a general must be

interpreted as specific in the sense that a particular general is under discussion (Siemund, 2000).

(20) A general has commanded the army himself.

This conclusion is in agreement with the fact that regardless of the reading of the intensifier, it

cannot interact with the indefinite pronoun someone as long as it is not read specifically. This is

exemplified below for the alone reading ((21) is provided by Siemund (2000)).

(21) ? Someone wrote me a letter himself.

Note that the example in (19b) can be rendered felicitous when a suitable context is provided that

forces the indefinite‘s interpretation to become generic, as shown in (22).

(22) Context: Discussion about what responsibilities engineers and their assistants are supposed

to have

Speaker A: I think that an engineer‘s assistant is responsible for knowing what new research

is being developed.

Speaker B: No, I disagree, I think an engineer himself should know this.

The examples below illustrate the same point for the also (23), even (23), and as for (24)

readings. The only way for (23) - (24) to be felicitous is if the DP in question is interpreted as a

generic or specific indefinite. Note that in (23) the intensifier can be an instance of either the also

or the even reading.

(23) a. Context: The whole country was surprised by the recent political scandals.

13

We remain agnostic as to why this reading is less contextually dependent compared to the rest of the

readings in terms of its ability to achieve a generic/specific interpretation on the indefinite.

UCLWPL 2011.01

90

A politician was surprised himself. (generic/specific reading)

b. #A politician was surprised himself. (true indefinite reading)

(24) a. Context: Discussing about which animals can be pets.

Speaker A: Even though the dog is a species that comes from the wolf, it can easily be a

pet.

Speaker B: Well, I don‘t know whether this is the case for every dog breed, but a wolf

itself can certainly not be someone‘s pet. (generic reading).

b. # A wolf itself can certainly live less than a hundred years. (true indefinite reading)

Again, we reach the same conclusion as with the animacy parameter. There is no variation

between the intensifier readings as far as the definiteness nature of the head-DP is concerned.

None of them can interact with a true indefinite DP; a commonality that on the one hand again

points towards one lexical entry and on the other indicates a fundamental property of the

intensifier (the centrality effect). This is discussed in the next section, the core proposal of the

paper14.

3. Deriving the various readings of the intensifier (the proposal)

We propose that an intensifier and its associate DP always fulfil the information-structural role

of a topic or a focus. Furthermore, it may or may not be interpreted contrastively, just like topics

or foci that lack an intensifier. The presence of the intensifier gives rise to an additional

interpretive effect though: the characterisation of the value denoted by the associate DP as

central. In section 3.1. we discuss, and adopt, Eckardt‘s (2001) insight that the intensifier denotes

a truth-conditionally meaningless function ID (x). The exact predictions of our proposal depend

on one‘s view of information structure and particularly the interpretations of topics, foci and

contrast. Hence in section 3.2. we outline Neeleman and Vermeulen‘s (2010) approach towards

these notions, which is (slightly modified but essentially) adopted in this paper. In sections 3.3. 3.10. we discuss how the various readings of the intensifier-associate DP constructions fit with

the information structural typology of Neeleman and Vermeulen (2010) and reach the conclusion

that there is only one lexical entry for the intensifier. The intensifier‘s various readings boil down

to the nature of its information-structural role (mainly), which in turn is determined by the

context. Section 3.11. attempts to provide an explanation of why the intensifier is incompatible

with true indefinites.

3.1. The meaning of the intensifier

14

Note that, contrary to the rest of the readings of the intensifier we discovered up to this point, the only

reading is not felicitous with any type of indefinite DP . This is shown below.

a)

Speaker A: I want to buy a pencil and a pen.

Speaker B: #I think you should buy a pen itself. (specific/generic reading)

This, however, does not create any problems for our attempt to unify all the readings of the intensifier under one

lexical entry because, as will be discussed in detail later in the paper, what we call the only reading is not an

intensifier reading to begin with.

UCLWPL 2011.01

91

In an attempt to explain why the intensifier consistently evokes a set of alternatives to the

associate DP that it is intuitively linked to, Eckardt (2001) proposes that it is the intensifier‘s

interaction with focus, and not a property of the intensifier itself, that is responsible for it. In

particular, Eckardt, who follows Moravcsik (1972), suggests that the core meaning contribution

of the intensifier is the identity function ID on the domain of objects De.

(25) ID: De De

ID (α) = α for all α ∈ De

According to this analysis, the intensifier is merely lexically specified with ID, which takes as its

input value a nominal constituent x, the associate DP, and maps it onto the same output value.

(26) exemplifies this operation for the DP John himself.

(26) 〚[John] himself〛 = ID (〚John〛) = 〚John〛

Adopting the assumption that the intensifier denotes ID is equivalent to saying that its core

meaning contribution to the sentence amounts to nil. We agree with this view mainly for two

reasons. One, it makes perfect sense from an interpretive perspective; the DP John himself does

not have a different denotation from John. Two, it predicts obligatory stress on the intensifier.

Eckardt proposes that the obligatory stress indicates that the constituent is in focus, and like

every other focused constituent, it evokes alternatives, contributing in this way to the meaning of

the sentence; hence, the invariable presence of alternatives in intensifier constructions15.

However, this picture is overly simplistic. Eckardt takes it for granted that the stress on the

intensifier is usually associated with emphatic focus (hence the surprise inference), whilst we

have seen examples in which an intensifier and its associate fulfil another information-structural

role, namely that of contrastive topic (see example (15)). Even though she notes that such a

reading (with a hat contour accent) is indeed possible, she only states that this use of the

intensifier, along with some other uses (i.e. in contexts of question-answer focus and of use of

the focus particle only), does not express surprise. What would be more interesting though is to

find out what this reading does express and how it is achieved, as well as to figure out a way of

unifying all the no-surprise cases (as Eckardt calls them) with the surprise ones. The stand we

take in this paper suggests that the notion of surprise is simply redundant in accounting for the

full range of uses of the intensifier. Instead, we need the notions of contrast, topic and focus, as

described by Neeleman and Vermeulen (2010), in order to capture the underlying mechanisms

that govern the possible readings of the intensifier.

We propose that the intensifier and its associate DP can potentially take the form of any

notion, or a possible combination of the notions, of the component of information structure,16

15

It has to be noted that Eckardt makes the crucial assumption that the intensifier is in focus and the associate

DP in its propositional background and it is this kind of relationship that eventually gives us alternatives to the

associated DP and not alternatives to the intensifier itself. The technical details of this process are discussed later in

this paper.

16

As Neeleman and Vermeulen (2010) point out, these notions can be of a discourse nature targeted by

mapping rules operating between different components of grammar (i.e. information structure and syntax). As far as

we can see, this does not create any issues for our approach here.

UCLWPL 2011.01

92

which comprises [contrast], [topic] and [focus]. These notions are organised systematically as

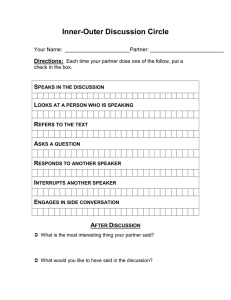

shown in the table below, (first presented by Neeleman and Van de Koot 2008)).

(27)

Contrast

Topic

Focus

Aboutness topic

[Topic]

New information focus

[Focus]

Contrastive Topic

[Topic, Contrast]

Contrastive Focus

[Focus, Contrast]

The table expresses that topic and focus are basic notions of information structure that can be

enriched to yield a contrastive interpretation. This results in the following four way typology of

information structural categories; focus, topic, contrastive focus, contrastive topic. The

independent existence of these categories and their linguistic relevance have been extensively

argued in various works (Reinhart 1981; Rizzi, 1997; Kiss 1998; Vallduvi and Vilkuna, 1998;

Molnar, 2002; Neeleman and van De Koot, 2008; Neeleman and Vermeulen (2010); among

others). As will be illustrated, the interpretive characteristics of these categories constitute the

basic interpretive aspects of the various readings of the intensifier.

3.2. The interpretation of [contrast], [topic] and [focus]

The Selfish Gene in (28B) is commonly assumed to be in focus because it corresponds to the whexpression found in (28A).

(28) Speaker A: What did John read?

Speaker B: He read [The Selfish Gene]F.

As pointed out by Selkirk (1984, 1996) and others, the focused constituent receives the main

stress of the sentence. Following Rooth (1985, 1992), Neeleman and Vermeulen (2010) suggest

that the focused constituent evokes a set of alternative propositions that differ only in the focused

position and share all the rest of the material, the focus value of the sentence. The ordinary value

of the sentence is the proposition expressed by the sentence. Below are the ordinary and focus

values of (28B).

(29) Ordinary value: [John read The Selfish Gene]

Focus value: {[John read The Selfish Gene], [John read The Blind Watchmaker], [John

read The Ancestor‘s Tale], [John read The Extended Phenotype],...}

The information in (29) can be represented in the somewhat different notational variant of (30)

provided by Neeleman and Vermeulen (2010), which we adopt in this paper for reasons of

simplicity.

(30) <λx [John read x], The Selfish Gene, {The Selfish Gene, The Blind Watchmaker, The

Ancestor‘s Tale, The Extended Phenotype,...}>

UCLWPL 2011.01

93

When (28B) is compared to (31B) below, there is an interpretive difference17. Whereas in the

latter example the focused constituent stands in opposition to an alternative explicitly mentioned

in the discourse, in the former there is no explicit alternative and no sense of contrast (Neeleman

and Vermeulen, 2010).

(31) Speaker A: John read The Extended Phenotype.

Speaker B: (No, you‘re wrong) THE SELFISH GENE he read.

(31B) is an instance of a proposition containing a constituent which is interpretatively a

combination of the notions of focus and contrast, a contrastive focus. Neeleman and Vermeulen

(2010) propose that contrast corresponds to a quantifier which gives information about the

relation between two sets, similarly to every other quantifier (i.e. every, some). On this view,

contrast in (31B) expresses to what extent the set α of contextually relevant books is contained in

the set β of things that John read. Two assertions are made: a) one member of α is also a member

of β, and b) there is at least one other member of α that is not contained in β (The Extended

Phenotype). The presence of alternatives and the positive statement in (a) are a result of the

semantics of focus, whereas the negative statement in (b) is a result of the semantics of contrast.

Therefore, contrastive focus and regular focus differ in that only the former encodes a negative

statement. The interpretation of (31B) is shown below in (32).

(32) a. <λx [John read x], The Selfish Gene, {The Selfish Gene, The Blind Watchmaker,

The Ancestor‘s Tale, The Extended Phenotype,...}>

b. x [x ∈ {The Selfish Gene, The Blind Watchmaker, The Ancestor‘s Tale, The

Extended Phenotype,...} & [John read x]]

Contrary to what is the case with the notion of focus, researchers have not reached a consensus

with respect to the content and linguistic relevance of the notion of topic (compare Chafe 1976,

Reinhart 1981, Vallduvi 1992, Lambrecht 1994). We follow Neeleman and Van de Koot (2008)

and Neeleman and Vermeulen (2010), who in turn follow Reinhart (1981), in characterizing

topics in terms of ―aboutness‖. Note that Neeleman and Vermeulen (2010) draw a clear

distinction between ‗discourse topics‘ and ‗sentence topics‘. Discourse topics refer to entities

that a unit of discourse is about, whereas sentence topics refer to the syntactic constituents used

to introduce a referent that the sentence is about. Since the notion of discourse topic is not

directly relevant to this paper, henceforth we refer to the notion of topic as to mean sentence

topic. The subject in (33B) is an instance of topic.

(33) Speaker A: Tell me about one of your friends.

Speaker B: Well, [Maxine]T was invited to a party by Claire on her first trip to New

York.

Similarly to foci, topics are associated with a set of alternatives. However, contrary to the

propositional nature of the focus alternatives, the lambda operator generates utterances. The

representation of topic differs from that of focus in that the function contains an assertion

operator, which means that its application derives utterances rather than propositions. The

17

Instances of contrastive focus are represented with SMALL CAPS throughout the rest of the paper. According

to Jackendoff (1972), contrastive focus requires an A-accent in English, a plain high tone (H*) often followed by a

default low tone. Regular focus on objects is usually marked with nuclear stress.

UCLWPL 2011.01

94

representation of the ordinary value and topic value (in parallel to the focus value) of (33B) is

shown below as (34). Note that the representation below is in accordance to the intuition that the

speaker performs the following speech acts when uttering (33B): a) Consider Maxine (out of a

set of possible topics); b) I assert that Maxine was invited by Claire to a party in New York.

(34) <λx ASSERT [x was invited by Claire to a party in New York], Maxine, {Maxine,

Susan, Bill,...}>

Similarly to the notion of focus, the notion of topic can also be interpreted contrastively. In (35),

Maxine stands in opposition to an alternative explicitly mentioned in the discourse, Bill.

(35) Speaker A: Tell me about Bill. Was he invited to a party when he went to New York?

Speaker B: Well, I don‘t know about Bill, but Maxine was invited to a party on her first

trip to New York by Claire.

Since the alternatives evoked by topics (and contrastive topics) are utterances, and not

propositions as is the case for focus, the interpretational effect associated with contrast is that the

speaker is unwilling to make (at least) one alternative assertion. As Vermeulen (2010) points out,

since contrastive topic is an utterance level notion, the reason for not committing to an

alternative utterance must be pragmatic (i.e. the speaker does not want to be held responsible for

the information conveyed by the relevant alternative). In a nutshell, Neeleman and Vermeulen

(2010) suggest that contrastive foci deny at least an alternative proposition, whereas contrastive

topics indicate that the speaker is unwilling (for a pragmatic reason) to make an alternative

utterance. (36) constitutes the interpretation of (35B).

(36) a. <λx ASSERT [x was invited by Claire to a party in New York], Maxine, {Maxine,

Susan, Bill,...}>

b. y [y ∈ {Maxine, Bill, Susan,...} & (y λx ASSERT [x was invited by Claire to a

party in New York])].

Equipped with the interpretation of the notions of contrast, topic and focus, and their

possible combinations, we are now able to derive all the readings of the intensifier. As

previously suggested, we hypothesize that the intensifier and its associate can carry these

information-structural interpretations (i.e. focus, topic), or a combination of them (i.e. contrastive

focus, contrastive topic). We will argue that each reading of the intensifier can be explicated in

terms of the interpretive characteristics of one of these notions. The analysis that follows

concentrates on the English intensifier, and as we will see the approach advocated here not only

captures the readings already discussed, but makes predictions regarding the possible readings of

an intensifier. Importantly, these predictions are borne out by the discovery of readings that, to

our knowledge, have gone unnoticed (i.e. the reading marked as topic).

3.3. The in person reading

The reading of the intensifier that has undoubtedly attracted most interest in the prior literature is

the in person one. Suppose the intensifier is associated with an argument a and that P is the

predicate resulting from performing lambda abstraction on a. Then the meaning contribution of

the in person reading can be summarized as follows; a) it evokes a set of alternative referents

that includes a, b) it structures this set into a central element a and peripheral elements {b, …}

UCLWPL 2011.01

95

(König and Siemund 1999, Siemund 2000, Eckardt 2001, Hole 2002, Gast 2006, among others),

and c) (P(a) is true, while application of λx.P(x) yields a false proposition for (at least) one of the

evoked alternatives. These characteristics are now discussed in more detail. (37) contains an

instance of the intensifier with the in person reading. The intensified value is the direct object.

(37) Yesterday, I saw [DP John himself].

An important property of the intensifier construction in (37) is the evoking of a set of alternative

sentences, which are formed by replacing John himself with alternative DPs. Even though it

seems tempting to assume that the DP John himself is just like every other constituent that is

focused, such an analysis runs into problems when considering (28) repeated below as (38).

(38) Speaker A: What did John read?

Speaker B: He read [The Selfish Gene]F.

There are two main differences between the sets of alternatives of (37) and (38B), as first pointed

out by Gast (2006). The first one has to do with the saliency of these alternatives. The intensifier

in (37) invariably makes reference to contextually given alternatives, which are evoked if not

present (i.e. Yesterday, I saw [DP the brother of John]). This is not the case for (38B), which does

not evoke any specific alternatives (i.e. He read [The Extended Phenotype] F). Thus, unlike what

is the case for (37), the person uttering (38B) does not need to have any particular alternatives in

mind. The second difference has to do with the nature of the evoked alternatives, namely the fact

that in the case of (37), the alternatives must have something to do with the associate DP.

Moreover, the associate‘s referent must be central with respect to the referents denoted by the

alternative values, the entourage. This requirement is exemplified in (39). Assuming that there is

not some sort of relation holding between Mary and John, the option of identifying the referent

of the alternative value (Mary) as peripheral to the referent of the intensified DP is ruled out;

hence Speaker B‘s reply in (39b) is infelicitous. On the other hand, the use of the intensifier in

(39a) is felicitous because the referent of the alternative value (the brother of John) is identified

through the intensified referent, John, by the use of the relational noun brother of18, hence the

understanding of John as being central.

(39) a. Speaker A: Bill told me that you saw the brother of John yesterday.

Speaker B: No, no, yesterday I saw John himself.

b. Speaker A: Bill told me that you saw Mary yesterday.

Speaker B: #No, no, yesterday I saw John himself.

As Gast (2006) points out, the centrality effect imposed by the intensifier on its associate DP is

not found in focus constructions. Focused constituents allow reference to alternatives that are

only restricted in terms of their semantic type. The contrast between a constituent which is

intensified and one which is focused is also visible in the example provided by Gast (2006) in

(40), once we assume that there is no historical or contextual relationship between the two

islands, in which Hawaii is central and Tahiti peripheral (i.e. Tahiti is financially dependent on

Hawaii).

18

Note that the use of relational nouns, such as bother of, sister of etc is not a prerequisite for the felicitous use

of the intensifier. See Siemund (2000) for a list of contexts that fulfil the requirements of the felicitous use of the in

person reading.

UCLWPL 2011.01

96

(40) a. #I have never been to Hawaii itself, but I‘ve been to Tahiti.

b. I have never been to [Hawaii]F, but I‘ve been to [Tahiti]F.

What can be concluded from the examples above is that the intensifier can only associate

with values that have been previously rendered as central in discourse, in some way. In (39a) for

instance, the alternative value brother of John is a possessive construction consisting of two

entities, namely the brother and John. As Nikolaeva and Spencer (2010) point out, the

relationship between the possessor and the possessee is largely asymmetric. Following various

authors, they further point out that the possessors function as pragmatic anchors (J. A. Hawkins

1978; R. Hawkins 1981; Fraurud 1990; Koptjevskaja-Tamm 2000, 2004) or reference points for

identifying the possessee (Langacker 1993, 1995). For (40a) we pointed out that the intensifier

can be used felicitously only if a similar asymmetric relationship (i.e. Tahiti is dependent in

some way on Hawaii) holds, a priori, between the intensified value and its alternative.

Apart from structuring a set of salient alternatives into a centre and periphery, the in person

reading exhibits one last significant function. It opposes the referent of the intensified DP to the

referents of the evoked alternative values, and, importantly, excludes at least19 one of the

corresponding alternative propositions. (41) means that the president, and not someone else

related to him (i.e. the president‘s secretary, the vice-president), will perform the action

described by the predicate.

(41) The president himself will announce the decision of the cabinet (and not his secretary).

Again, the exclusion of alternatives is not necessarily found in focus constructions. Speaker B‘s

reply in (28), repeated below as (42), is not interpreted as excluding an alternative (i.e. John read

[The Extended Phenotype]F).

(42) Speaker A: What did John read?

Speaker B: He read the [The Selfish Gene]F.

Taking into account the interpretation associated with the information structural categories

predicted by the typological table in (27) and the various aspects of the meaning contribution of

the in person reading, we may hypothesize the following:

(43) Hypothesis 1 (first draft): The in person reading of the intensifier is invariably an

instance of contrastive focus.

19

We stress the point that the in person reading is not understood exhaustively (in the sense of Kiss 1998, i.e.

negates all alternatives), but only contrastively. After all, if it were the case that this reading is characterized with

exhaustivity the example below should be, but is not, infelicitous. As can be seen, someone peripheral to Mary, her

brother, is not excluded from the action denoted by the predicate. The fronting of the intensifier-DP construction

ensures that it is interpreted contrastively (see Neeleman and Van de Koot 2008). This is in accord to our hypothesis

below that the in person reading and its associate DP are interpreted as contrastive focus.

a)

Context: John intends to marry Mary. However, it is tradition that he has to meet her whole family in order

to be approved by them.

John’s mother: John met Mary yesterday!

John’s father: Yes, Mary HERSELF he met, her BROTHER he also met, but he didn’t meet the rest of her

family.

UCLWPL 2011.01

97

Given that the intensifier i) denotes the function ID (x) (that maps its input to the same output),

ii) is satisfied by a nominal constituent, namely the associate DP that it is intuitively understood

to interact with, iii) is (contrastively) focused and iv) that the effect of such focusing is the

inducing of alternatives of the same semantic type as the asserted value (Rooth, 1985, 1992), the

alternative values that are induced should also be functions from De to De. In the case of the in

person reading, we assume that ID (x) contrasts with the function DEP (x), which is paraphrased

as an entity dependent on (x) (see Eckardt 2001, Hole 2002, Gast 2006 for similar approaches).

Let us call this function the dependent function. This function, by definition, restricts the

alternative values to x (x = the value denoted by the nominal constituent interacting with the

intensifier) to only those that are peripheral to x, because it encompasses the asymmetrical

relationship holding between the entity x and some other entity in the alternative value. Contrary

to ID (x) though, DEP (x) does not map its input onto the same output, when applied to x (in the

same fashion as ID (x)). Assuming that one of the evoked alternatives to the DP Hawaii itself is

Tahiti, DEP takes Hawaii as its input and maps it onto an entity dependent on Hawaii, which in

this case is Tahiti. This process is exemplified below.

(44) 〚Tahiti〛 = DEP (〚Hawaii〛) = 〚an entity dependent on Hawaii〛 = 〚Tahiti〛

Note that our approach is significantly different from authors (Eckardt 2001, Hole 2002 among

others) who assume that the centrality effect is a result of the fact that the alternative values are

structured around the intensified value. To make things more transparent, these authors assume

that the centrality effect simply results from the presence of the intensified value in the

alternative values. It is true that the alternative values invariably consist of the intensified entity

(and some other entity). This can be seen in (44), in which the alternative value of Hawaii,

Tahiti, is indeed defined in terms of Hawaii, through the application of DEP. However, despite

the attractiveness of this approach, it falls short in expressing the fact that the intensified value

needs a specific type of alternatives (the entities found in the alternative values must be a priori

structured in a centre-periphery fashion). The mere presence of the intensified entity within all of

its alternative values is not enough. In fact, this assumption makes the wrong predictions. As we

will see in section 3.6 an explanation of centrality along these lines over-generates, in the sense

that it predicts impossible alternative values for the intensified value, and hence readings of the

intensifier that do not exist. On the other hand, our approach suggests that the alternative values

are structured around a central element x beforehand (intensification) with various means such as

the use of the possessive construction or historical events that make a country dependent on

some other one (see example (40a) and surrounding discussion). This asymmetric relation

between the entity that eventually becomes the intensified value and another entity, both forming

part of the alternative value, is precisely what DEP expresses. Of course, for this asymmetric

relation (or for any relation) to exist, both entities need to be present in what we call the

alternative value. Therefore, the consistent presence of the intensified value in the alternative

values is merely an epiphenomenon. Notice that the assumption that ID (x) contrasts only with

DEP (x) predicts that the intensifier will only associate with DPs whose denotations are central,

hence the in person reading‘s observed centrality effect is explained. For the sake of

completeness we would like to point out that, on a par of the possessive construction, there are

other ways of expressing an asymmetric relation between two entities that constitute part of one

syntactic constituent, and hence are felicitous alternatives to the in person reading and its

UCLWPL 2011.01

98

associate DP. The example below illustrates this. The subject is a complex DP consisting of the

head DP and its modifier. The modifier, near the table, functions as a reference point for the

identification of the head DP, the chair. This is reminiscent (see above) of the role played by

(and hence the asymmetric relation between) the entities in a possessive construction. However,

contrary to the asymmetric relation expressed by possession, the relation holding between the

entities in the subject constituent of the example below is a relation of distance, as expressed by

the preposition near. The fact that we are able to define, with no particular difficulty, the nature

of the relation expressed by near will become particularly important later on, when we will

discuss the exact nature of the entities comprising the alternative referents of the intensified DP.

(45) Speaker A: The chair near the table looks nice.

Speaker B: Well, I think that the table ITSELF looks nice. The chair is awful.

We have not yet explained though the requirement of this reading to interact with salient

alternatives and the effect of excluding them (as will become more explicit in the representations

given in (47) and (48), this reading does not interact with, and exclude, the salient alternative

values themselves but alternative propositions involving these alternative values). This is where

the notion of contrast comes into play. As pointed out above, contrast has two main functions.

One, it refers to alternatives explicitly mentioned in discourse or evokes them if not present; in

other words it requires salient alternatives. Two, when combined with the notion of focus, it

excludes (at least one of) these alternatives, which have the form of propositions. Based on these

parallel interpretational effects, it seems reasonable to analyse the DP that interacts with an

intensifier with the in person reading along the lines of a contrastively focused constituent.

A note is in order here with respect to (43). (43) states that it is the intensifier itself, and not

the DP it interacts with, that is contrastively focused marked. This means that, contrary to a

regularly contrastively focused marked constituent, the intensified nominal constituent is not

marked as such. The interpretation of this constituent as a contrastive focus occurs indirectly

through its interaction with the intensifier (and as we have seen it is this indirect route that also

gives rise to the centrality effect). The representation of (37), repeated below as (46) without

yesterday for the sake of simplicity, is shown in (47)20.

(46) I saw John HIMSELF.

(47) a. <λx [I saw x], John, {John, DEP_1_(John), DEP_2_(John), ..., DEP_n_(John)}>

b. x [x ∈ {John, DEP_1_ (John), DEP_2_(John), ..., DEP_n_(John)} & [I saw x]]

In order to see more clearly the effect of context with regard to restricting the set of alternatives,

the representation of speaker B‘s utterance in (39a) is provided below in (48). This time the set

of referents is closed and consists only of two entities as specified by the context. As the

semantics illustrate below, the brother of John is represented as DEP (John).

20

We will follow this type of representations throughout the rest of the paper. However, we are aware that this

representation disregards issues having to do with the position of the intensifier. This representation and every one

that follows essentially take it for granted that the intensifier always takes scope over the entire proposition/utterance

(as there are never variables that are closed off through existential closure), something which cannot always be right.

Further research is needed in order to determine whether the intensifier is able to take different scope from the one

determined by its position in surface syntax, and if this is possible, whether there are any restrictions in this process.

UCLWPL 2011.01

99

(48) a. <λx [I saw x], John, {John, DEP (John)}>

b. x [x ∈ {John, DEP (John)} & [I saw x]]

(48) expresses to what extent the set of contextually relevant entities (i.e. John, the brother of

John, etc) is contained in the things that I saw. It is asserted that one member of this set of

entities is also a member of the set of things that I saw. It is also asserted that there is at least one

other member of this set that is not contained in the set of things I saw (i.e. the brother of John).

Similarly to a constituent marked with contrastive focus, the presence of alternatives and the

positive statement are a result of the semantics of focus, whereas the negative statement is a

result of the semantics of contrast. Contrary to just any other contrastively focused constituent

however, the presence of the in person reading in (39a) and (46) constrains the members of the

set of alternatives in such a way that only certain variants of the proposition I saw John can be

included. The position held by John in these variants can only be filled by constituents denoting

referents peripheral to John (i.e. the brother of John), and nothing else.

All things considered, the meaning contribution of an intensifier carrying the in person

reading is crucially a result of the interpretational effects of contrastive focus interacting with ID

(x). This interaction evokes a particular type of alternatives, which are assumed to be the

dependent function(s). We may therefore replace (43) with the more articulated hypothesis in

(49).

(49) Hypothesis 1 (second and final draft): The in person reading of the intensifier is invariably

an instance of contrastive focus and always makes reference to dependent function(s).

It is now predicted that the felicity conditions of the in person reading should show parallel

behaviour to the conditions of a contrastively focused constituent. A comparison between (50)

and (51) illustrates that this prediction is borne out.

(50) Speaker A: What did John read?

Speaker B: #THE SELFISH GENE he read.

(51) Speaker A: Who did you see yesterday?

Speaker B: #I saw John HIMSELF, yesterday.

As Neeleman and Vermeulen (2010) point out, speaker B‘s answer in (50) is infelicitous in that

context because the contrast implied by The Selfish Gene and some other reading material cannot

easily be accommodated by speaker A. This is because the alternative reading material is not

made accessible to him/her in the discourse. As a result, speaker B‘s answer is likely to trigger a

request for clarification, such as What do you mean? What did he not read? It has to be noted

here that the requirement for availability of salient alternatives is intrinsically connected to the

main function of contrast, which is to negate alternatives. In order to successfully negate

alternatives, the speaker/hearer must have them under consideration. Therefore, the requirement

for salient alternatives in contrastive contexts can be seen as a by-product of the function of

contrast to negate them. The situation in (51) is similar to that of (50). Speaker B‘s reply is

infelicitous because the contrast implied by the DP John himself and someone else related to

John cannot easily be accommodated by speaker A. This is due to the unavailability of salient

alternatives that the contrastively focused intensifier and its associate DP need to make reference

UCLWPL 2011.01

100

to. However, as pointed out above, if these alternatives are not salient, the intensifier evokes

them. Thus, speaker B‘s reply will trigger a request for clarification along the lines of What do

you mean? Who didn’t you see (related to John)?

The analysis proposed for the in person reading also accounts for another reading of the

intensifier, the delegative. Its use is understood as ―the intensified referent‖ has done the action

denoted by the predication instead of having it done by someone else. In the example below for

instance, Mary is understood to have done the action of dying her hair instead of having someone

else (i.e. the hairdresser) performing the action for her.

(52) Speaker A: The hairdresser dyed Mary‘s hair.

Speaker B: No, Mary has dyed her hair HERSELF (and not the hairdresser).

Similarly to the in person reading, the proposition in (52B) can have a continuation of the sort

and not x. This is because it is understood as negating an alternative proposition that differs with

the one asserted only with respect to the position occupied by the intensified referent (and the

absence of the intensifier). Hence, the proposition in (52B) contrasts with a proposition of the

sort in (52A). The question that arises then is how do we get the extra inference in the case of the

delegative reading, namely that the alternative referent contained in the excluded alternative

proposition performs an action on behalf of the intensified referent. We think that this is clearly a

result of pragmatics. The delegative reading comes across only when the intensified referent has

a direct interest in the action described by the predicate. In the case of (52B), Mary has a direct

interest in the action of dying her hair. Note that the delegative reading is always accompanied

in the predication by a possessive DP of the type her hair (where her refers to the intensified

referent). The presence of such DPs is what expresses the direct interest of the intensified

referent in the denoted action. Once we attempt to change the referent of her in (52), as in (53)

below, the delegative inference becomes unavailable. Instead, as expected, the in person reading

arises.

(53) Mary has dyed Jane‘s hair HERSELF, and not the hairdresser.

Another contextual factor that decides among the two readings is the type of the verb that is

present in the predication. According to Eckardt (2001), the use of the delegative reading is

restricted to combination with agentive verbs (or verbs denoting an action). As shown in (54),

the intensifier can only be an instance of the in person reading (again as expected when the

delegative inference is removed). This is because of the stative nature of the verb.

(54) John is a gardener HIMSELF (not his brother).

This restriction is expected once we consider the interpretative contribution of the delegative

reading (see above). It is inconceivable for someone Y to be a gardener for someone X. We can

think of the delegative reading as a way of transferring whatever is denoted by the predication,

from Y (the alternative referent) to X (the intensified referent). The only conceivable things that

can be transferred and simultaneously be denoted by verbs are actions, hence it is restricted to

occur only with agentive verbs.

In the same way that the in person reading requires that the intensified referent is central,

the delegative reading requires Mary in (52) to be central and the hairdresser as the entourage.

UCLWPL 2011.01

101

This kind of asymmetric relation is defined against the denotation of the rest of the predication,

which is about dying Mary‘s hair. Therefore, we suggest the same analysis for the delegative

reading as for the in person one. ID (x) is contrastively focused and evokes the dependent

function (DEP (x)), whose application on the intensified referent will deliver the hairdresser in

the alternative (and excluded) proposition of (52B), in (52A). This process is shown below21.

(55) 〚the hairdresser〛 = DEP (〚Mary〛) = 〚an entity dependent on Mary〛 = 〚the

hairdresser〛

The example in (56) further substantiates that the delegative reading and its associate DP are

interpreted as contrastive focus, as its infelicity in a context of question-answer focus illustrates

(for those who find this example felicitous, it is because there is evocation of alternative values

that include something like the hairdresser. This further shows that this reading must be

interpreted contrastively in order to be felicitous).

(56) Speaker A: Who has dyed Mary‘s hair?

Speaker B: #Mary has dyed her hair HERSELF.

3.4. The alone reading

Example (57) contains an intensifier with the alone reading. Its use gives rise to the inference

that the subject referent performs the action described by the predicate alone or without help

(hence widely called the assistive reading in the literature), hence the felicitous (albeit slightly

redundant) continuation of the sentence without Bill.

(57) John found the way to the station himself (without Bill).

In contrast to what happens with a simple new information focus (see the discussion surrounding

(42), the intensifier in (57) forces us to consider someone that did not participate together with

John in the action of finding the way to the station (i.e. someone who usually gives directions to

John). To put it otherwise, the main contribution of this reading is to state that the intensified

referent has acted without the external input of some other agent. This fact points towards a

constituent whose function is to evoke alternative referents (to its associate DP) and at the same

time to exclude them from the action described by the predicate. In fact, we can be more specific

than that, and say that the sentence containing the alone reading contrasts with, and negates, a

salient alternative proposition stating that the action denoted by the proposition containing the

intensifier is carried out by the intensified referent together with some other entity. This means

that (57) contrasts with, and negates, something like (58 below.

(58) John found the way to the station with Bill.

Following this reasoning, we conclude that the alone reading along with its associate DP is an

instance of contrastive focus.

21

To save space and to avoid repetition, we do not provide a formalised analysis of this reading. The reader should

assume that it is the same as with the in person reading.

UCLWPL 2011.01

102

However, at first sight the centrality status required by this reading on its associate DP

differs from the one required by the in person one. As pointed out above, the in person reading

requires the entity that is subsequently intensified to be related in some asymmetrical way (i.e.

through kinship relations, financial dependence, distance) with another entity in the alternative

value. This, we argued, led the way for the intensified value to be understood as central within

the alternative value. On the other hand, the alone reading does not seem to impose this kind of

requirement on the entities being present in discourse. Even if we consider the most extreme

situation in which John and Bill do not know each other, the example in (57) remains felicitous.

In order to understand why this is the case, we need to take a closer look at what the alternative

values of the intensified value in (57) look like.

Once we agree that (57) contrasts with something like (58), the alternative value of the

intensifier and its associate DP John in (57) must be John with Bill and not simply Bill. If it were

just Bill, then we should be able to have a continuation of the sort and not Bill. However, this

continuation does not give rise to the targeted reading but the in person one. The only felicitous

continuation of propositions containing the alone reading of the intensifier must consist of

something that means, or is semantically equivalent to, without y (i.e. not in the company of y).

Two things can be concluded from the above discussion. One, the alternative value of the

alone reading and its associate DP x is x with y. Crucially, it is not just y. Two, the alternative

propositions evoked with the use of the alone reading are invariably an instance of a concomitant

construction. Concomitant constructions are the linguistic means of expressing a relation