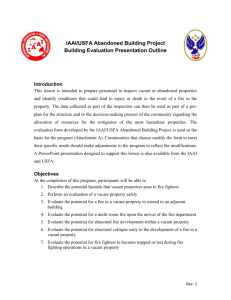

Managing Vacant and Abandoned Properties in Your Community IAAI/USFA

advertisement