From: AAAI Technical Report FS-02-04. Compilation copyright © 2002, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved.

User Demographics for Embodiment Customization

Andrew J. Cowell1 , Kay M. Stanney2

1

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, MSIN K7-28, 3350 Q Ave, Richland, WA, 99352

2

IEMS, University of Central Florida, CEBA 249 Orlando, FL 32816

1

andrew@pnl.gov 2 stanney@mail.ucf.edu

Abstract

Attempts at interface agent personalization are usually aimed at

helping the user perform a task or service. For example,

scheduling of appointments, inspection of messages, discovering

items of interest and different forms of negotiation. While this is

very noble undertaking, it makes assumptions about the level of

trust and credibility a user may place in such an agent in a real

world setting. If Microsoft’s experiments in social user interfaces

teach us anything, it is that a ‘one size fits all’ solution does not

truly engage the user and encourage reuse. This ‘relationship

management’ between the user and the character begins when the

two first meet. As with human-human relationships, first

impressions are essential. Instead of looking at the functional

aspects of the relationship, we believe the characters embodiment

is the best place to start the personalization process. We describe

a study in which participants from several different age ranges,

genders and ethnic groups were asked their preference of

anthropomorphic character, based on a cooperative computer

task. We found that participants generally selected characters

from the same ethic group as themselves and that almost all

participants selected a young character (instead of a middle aged

or elderly character). No significant preference was found for

character gender.

Elements of Embodiment

A user’s judgment of an anthropomorphic character, if

embodied naturally and realistically, can be assumed to be

based upon the same logic as used in everyday interactions

with other individuals. Such judgments are commonly

based upon stereotypical beliefs that one holds of the

referent’s social category or categories. This process of

forming an impression of a referent begins with an act of

categorization (Fiske & Neuberg, 1990) after which

stereotypic processes commence. A target may be

categorized on a number of dimensions (for example

gender, age, ethnicity, hair length, accent, music

preference, etc.) and belong to multiple categories

simultaneously. Stereotypes exist for broad categorizations

such as ‘males’ as well as more narrowly defined groups

such as ‘long haired, young males’. Certain researchers

(Fiske & Neuberg, 1990; Smith & Zarate, 1992) believe

stereotypes occur at more than one level with the most

specific subtype being the individual. While an individual

Copyright © 2002, American Association for Artificial Intelligence

(www.aaai.org). All rights reserved.

may be considered a combination of multiple dimensions,

an observer is not necessarily aware of all the possible

dimensions, restricting their observation to a small set of

obvious base characteristics, such as age, gender and

ethnicity (Gardner, MacIntyre, & Lalonde, 1995). In our

study, we took these three characteristics to be the

fundamental elements of our character embodiment. Age,

gender and ethnicity dimensions are discussed here with

the purpose of identifying differentiation, if any, in

preferred embodiment based on one’s own demographics.

Gender

The psychological literature indicates certain gender

stereotypes are pervasive in common culture. Even despite

recent upward trends in female social standing (Romer &

Cherry, 1980; Ruble, 1983), men continue to be perceived

as possessing stronger, functional attributes, such as

independence and assertiveness, while females are

perceived to hold more emotionally expressive

characteristics, such as kindness, sensitivity and need for

affiliation (Rosenkrantz, Vogel, Bee, Broverman, &

Broverman, 1968). From these perceived attributes evolve

several stereotypes. Robinson and McArthur (1982) found

that both men and women attend to male voices more

intently than to females voices. This may indicate that

computer characters should be embodied as male

characters to utilize the increased attention they appear to

demand. Based upon the perceived knowledge that the

genders have over their own characteristics described

above (i.e. functional attributes for males, expressive

attributes for females) it is often suggested that females

know more about typically feminine topics while males

know more about typically masculine topics. Heilman

(1979) found that certain occupations were commonly

identified as being either feminine or masculine. Due to

gender stereotypes, entrance to masculine careers is often

difficult for females and visa versa. Deaux and Emswiller

(1974) found that performance by a male on a masculine

task was substantially attributed as skill while the same

task completed by a female was attributed to luck. A

similar study by Feldman-Summers and Kiesler (1974)

found that male success was rationalized as high ability

while motivation and luck accounted for female success. In

human-agent interaction, the context of the application or

shared task would be where attribution of masculinity or

femininity would lie. For example, if the shared task were

to determine faults with a car engine, the stereotypical

context would be of a masculine task, whereas if the shared

task were flower arrangement the stereotypical context

would be of a female task.

Dominant behavior is another area where gender

stereotypes exist. In females, dominance and

aggressiveness are regarded as undesirable, whereas they

are permissible and even encouraged in males (Costrich,

Feinstein, Kidder, Maracek, & Pascale, 1975; Deutsch &

Gilbert, 1976). Nass, Moon and Green (1997) describe

males placed in dominant roles as “assertive” and

“independent”, whereas females are seen as “pushy” or

“bossy” (p. 865). Such gender affects could cause

unfavorable evaluations regardless of the quality of an

agent’s work.

As part of the ‘Computers As Social Actors’ program at

Stanford University, Nass, Moon and Green (1997)

performed studies to determine whether computers

embedded with gender cues would generate gender-based

stereotypic responses. Their results indicated strong

support for the ‘male evaluation’ stereotype. Both male and

female participants rated a male-voiced computer more

positively than a female-voiced computer. Their work also

supported the ‘masculine/feminine’ stereotype, although

the results were less definite. Finally, they supported the

‘female dominance’ stereotype, showing that femalevoiced computers that interacted in a dominant fashion

were rated as significantly less friendly as compared to

their male-voiced counterparts.

At first glance, this work appears to suggest that an agent

should be embodied as a male character to ensure

successful interaction. A male character may be attended to

more intently, and may not be penalized if it acts in a

dominant manner. A male-embodied agent may suffer in

feminine contexts (i.e. users’ may question the agents’

expertise), although Nass, Moon and Green found a

relatively weak effect. Such a decision would coincide with

findings in a study by Mack et al (1979) that found that

virtually all males (98%) and a high percentage of females

(85%) attributed male characteristics to a standard

computer. Unfortunately, this research is inconclusive.

None of this previous research has been based specifically

on realistic anthropomorphic agents. It is possible that a

referent may make a different choice when presented with

an geometrically accurate embodiment, versus a computer

that speaks with a male or female voice (Nass, Moon &

Green, 1997) or a computer that makes no effort to

engender itself (Mack et al, 1979).

Ethnicity

Ethnicity is another demographic variable that is easily

discernable early in an interaction cycle. Ethnic stereotypes

are often depicted on television and new media where the

ethnic spectrum is not homogeneous, with Caucasian’s

appearing much more frequently than any other ethnic

group. While African Americans appear more frequently

then they once did, they are often depicted negatively, as

criminals or perpetrators of violent crime (Gerbner, Gross,

Morgan, & Signorielli, 1986). A similar stereotype was

found in a report from the University of Washington that

compared the probation reports of black and white

juveniles. Black individuals charged with the same crime,

of the same age and having the same criminal history as a

white individual would have their crimes described as

being caused by internal attributes or aspects of their

character (e.g. being disrespectful toward authority or

condoning criminal behavior) while the white juveniles’

crimes would be more likely blamed on negative

environmental factors (e.g. exposed to excessive family

conflict or association with other delinquents). A study by

Peffley et al (1997) found similar negative stereotypes in

the context of state welfare. Even though many individuals

would not admit to harboring such negative stereotypes,

they are common and affect the manner in which people

interact with individuals from another ethnic group. Such

ethnic stereotypes may be extended to computer characters

at the user interface.

While such literature suggests that an African American

embodiment for a computer character would be an unwise

choice, a growing section of literature suggest that African

Americans hold their own racial stereotypes. Often labeled

as ‘reverse racism’, a growing body of literature indicates

ethnic stereotypes are reciprocal (Jaroff, 1994; Fish, 1993;

Gross, 1977; Lynch, 1989; Horowitz, 2000).

Another ethnic group to consider are Asian Americans.

Generally, the ethnic stereotypes describing Asian

Americans are not as negative as those describing African

Americans although they can be just as damaging. Many

see Asian Americans as the model minority (Delener &

Barlow, 1990) and “academic nerds” (“Asian Americans:

The Drive To Excel”, 1984 p.12), symbolizing educational

achievement and economic success. Such stereotypes

misrepresent the majority of Asian Americans and lead to

racial envy and, in some cases, violence (Yip, 1997). In

technological circles, such academic achievement

stereotypes have been extended to portray Asian

Americans as computer gurus (Taylor & Stern, 1997).

Yet another ethnic group to consider are Hispanic (Latino)

Americans. A review by Jackson (1995) suggests that

perceptions of Hispanics are generally unfavorable.

Hispanics are often viewed as lazy, cruel, ignorant and

belligerent but also as family-oriented and tradition-loving

(Fairchild & Cozens, 1981). Similarly, a study by Marin

(1984) administered to Anglo Americans saw Hispanics as

aggressive, poor and lazy, but also family-oriented and

proud. Studies indicate that Hispanics use similar

stereotypes when describing themselves (Montenegro,

1971; Peterson & Ramierez, 1971) and Horowitz (2000)

suggests this may be true for all ethnic groups.

While it is not the intent of this study to perpetuate ethnic

stereotypes, it is prudent to acknowledge them and their

role in human-human communication. All ethnic groups

appear to harbor their own out-group prejudices. They also

use similar stereotypes for people of their own ethnic

group.

Age

While many studies in human-computer interaction (HCI)

look at how age affects the manner in which an individual

interacts with a computer system, few studies were found

that look specifically at how age affects interaction and

specifically how the age of a computer character affects

credibility. De Meuse (1987) indicates that a ‘similar to

me’ hypothesis exists and this was supported in certain

studies. Rosen and Jerdee (1976) found that young

managers saw older personnel as more resistant to change,

less creative, possessing a lower physical capability for

work and less suitable for retraining. Cleveland and Landy

(1981) reported that older workers were rated low on ‘self

development’ and ‘interpersonal skills’ by younger

workers. Contrary to this, a study by Schwab and Heneman

(1978) found that older employees rated older secretaries

lower in ability than younger ones. This suggests there

exists some age function that describes the preferred age of

an interacting partner. For preteen users, there appears to

be a ‘big brother’ mapping where the user prefers a

character that is ‘older and wiser’ (Johnson, 1995).

Teenage users and users up to their late twenties may feel

more comfortable interacting with a character of the same

age. If the character were any younger, the user may

question their domain knowledge, but if the character were

any older it may be consider too old fashioned and out of

date (Benford, 1998). Older users may prefer a younger

character. They may regard a computer character their own

age as knowing as little as they do about technology and

thus being of little help. As younger generations are usually

associated with being at ease with new technology, older

users may believe they make the best computer associates

(Benford, 1998). This collective research suggests that an

age function may exist that potentially directs users of all

ages to select a youthful computer character.

To empirically substantiate the hypotheses put forth in this

study, a set of experiments was conducted. An experiment

was performed to determine the preferred demographic

embodiment and the results of this were filtered into a

larger experiment that sought to determine the level of trust

and credibility a participant would confer on a character

based on differing levels of nonverbal behavior.

Empirical Study

The purpose of the pretest was to determine the preferred

agent embodiment for the computer character. Unlike the

behavioral mechanisms that agents may use when

interacting with users, physical embodiment cannot be

dynamically changed during an exchange. Hence a method

was required to determine the best design practices for the

selection of demographic variables considered in this

dissertation (gender, age and ethnicity of a computer

character). The hypotheses for this pretest were driven by

the inconclusive suggestions from the literature review.

Hypotheses

The following hypotheses are offered (alternative

hypotheses in braces):

a

H0/1 :A computer character that matches the ethnicity of

the user shall [not] be seen as a more preferable interaction

partner than a character that is not from the same ethnic

group.

b

H0/1 :A computer character embodied as a youthful

character will [not] be seen as a more preferable interaction

partner than a character that is embodied as one of the

other age presets (middle-aged/elderly).

c

H0/1 :A computer character embodied as a male character

will [not] be seen as a more preferable interaction partner

than a character that is embodied as a female character.

Method

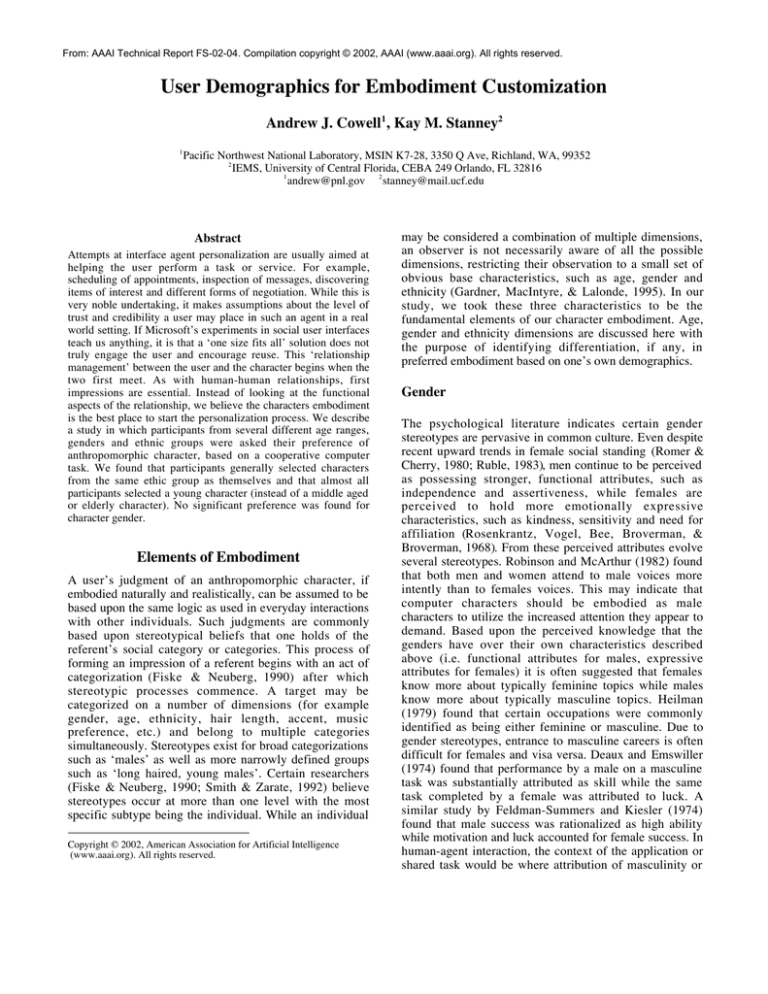

The experimental task was a card sorting assignment.

Cards featuring characters describing all 18 permutations

of the three demographic variables, as shown in the table

below, were shown to pretest participants and they were

asked to sort them in order of which character they would

prefer to work with in a cooperative computer task.

Table 1 - Embodiment Characteristics

Age

Young

Middle Aged

Elderly

Gender

Female

Male

Ethnicity

African American

Asian American

Caucasian

An example character (a middle aged Caucasian female) is

shown in Figure 1. A Latino/Hispanic character was also

included initially, but withdrawn before testing began due

to difficulties in expressing significant differences between

this and the appearance of the Caucasian character. All

characters shared the same neutral hair, eye and clothes

colors to reduce preference selection to the elements we

were controlling.

results of this study, the final characters were matched to

the ethnicity of the participant, and a young character was

used throughout. The participants were asked to select

between a male and female character. Informal feedback

from the participants indicated that the characters’

embodiment was natural and genuine. Those who had

interacted with other types of interface agent expressed a

preference for our anthropomorphic, realistic

embodiments.

This study provides some potential design guidelines that

may help direct embodiment decisions for those interested

in using anthropomorphic computer characters in their

applications. The essence of the guidelines is that research

across sociology, psychology, social psychology and

political science provides good indicators of how an

individual’s demographic profile influences an

interactional dyad and further supports the premise that

there is transfer between human-human communication

and human-computer characters when embodied

realistically.

Acknowledgements

Figure 1 - A Middle Aged Caucasian Female Embodiment

Results

Forty-five college students from the University of Central

Florida participated in the experiment. These included

twenty males and twenty-five females. The group included

twenty Caucasians, nine Asians and sixteen African

Americans. The participants ranged in age from college to

middle aged. For each demographic element, the

participants preferred choice was compared to their own

demographic values and a match or no-match recorded. For

each variable, a test of proportions was used to determine

participant preference. Results indicated that a significant

(p = 0.05) majority of participants selected a character

matching their ethnicity and that was young (based on the

task being a cooperative computing endeavor). While most

participants selected a character that was opposite of their

gender, this difference was not significant. Based on these

results, the ethnicity of the character for the main

experiment was set to match that of the participant, the age

of the character was set to ‘young’ and the gender of the

character was left to participant choice.

Conclusion

The empirical study discussed in this paper was used as a

pre-test for a more in-depth study of the use of trusting

nonverbal behaviors by computer characters to encourage a

more credible interaction (Cowell, 2001). Based on the

This work was supported by a doctoral fellowship from

Eastman Kodak Research Labs. The authors would like to

thank the Human Factors department at EKRL for their

encouragement and guidance.

References

Benford, R. D. (1998). Social Issues. New York, NY:

Macmillan.

Billings, J. P. (1988). A Study of Nonverbal Behaviors of

School Principles and their Relationship to the Principles'

Ability to Develop Trust and Motivate Staff. Claremont

Graduate School, Claremont.

Cleveland, J. N., & Landy, F. J. (1981). The Influence of

Rater and Ratee Age on Two Performance Judgments.

Personnel Psychology, 34, 19-29.

Costrich, N., Feinstein, J., Kidder, L., Maracek, J., &

Pascale, L. (1975). When Stereotypes Hurt: Three Studies

of Penalties in Sex-role Reversals. Journal of Experimental

Social Psychology, 11, 520-530.

Cowell, A.J. (2001) Increasing the Credibility of

Anthropomorphic Computer Characters: The Effects of

Manipulating Nonverbal Interaction Style and

Demographic Embodiment. Ph.D. Dissertation, University

of Central Florida, Orlando, FL.

De Meuse, K. P. (1987). A Review of the Effects of

Nonverbal Cues on the Performance Apraisal Process.

Journal of Occupational Psychology, 60, 207-226.

Deaux, K., & Emswiller, T. (1974). Explanations of

Successful Performance on Sex-Linked Tasks: What is

Skill for the Male is Luck for the Female. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 29, 80-85.

Delener, J. L., & Barlow, W. (1990). Informational

Sources and Media Usage: A Comparison Between Asian

and Hispanic Subcultures. Journal of Advertising Research,

30, 45-52.

DePaulo, B. M. (1992). Nonverbal Behavior and Self

Presentation. Psychological Bulletin, 111(2), 203-243.

Deutsch, C. J., & Gilbert, L. A. (1976). Sex-role

Stereotypes: Effect on Perceptions of Self and Others and

on Personal Adjustment. Journal of Counseling

Psychology, 23, 373-379.

Fairchild, H. H., & Cozens, J. A. (1981). Chicano,

Hispanic or Mexican American - What's in a Name.

Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 3, 191-198.

Feldman-Summers, S., & Kiesler, S. B. (1974). Those Who

Are Number Two Try Harder: The Effect of Sex on

Attributions of Causality. Journal of Personality & Social

Psychology, 30(846-855).

Gardner, R. C., MacIntyre, P. D., & Lalonde, R. N. (1995).

The Effects of Multiple Social Categories on Stereotyping.

Canadian Journal of Behavioral Science, 27(4).

Gerbner, G., Gross, L., Morgan, M., & Signorielli, N.

(1986). Violence Profile No. 14: The Annenberg School of

Communications, University of Pennsylvania.

Heilman, M. E. (1979). High School Students'

Occupational Interest as a Function of Projected Sex Ratios

in Male-Dominated Occupations. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 64, 915-928.

Jackson, L. A. (1995). Stereotypes, Emotions, Behavior

and Overall Attitudes Towards Hispanics by Anglos

(Research Report #10). Michigan: Julian Samora Research

Institute, Michigan State University.

Johnson, A. G. (1995). The Blackwell Dictionary of

Sociology. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

Mack, D., Williams, J. G., & Kremer, J. M. D. (1979).

Perception of a Simulated Other Player and Behavior in the

Reiterated Prisoner's Dilemma Game. The Psychological

Review, 29, 43-48.

Montenegro, M. (1971). Chicanos and Mexican

Americans: Ethnic Self-Identification and Attitudinal

Differences. San Francisco, CA: R & E Research

Associates.

Nass, C., Moon, Y., & Green, N. (1997). Are Machines

Gender Neutral? Gender-Stereotypic Responses to

Computers with Voices. Journal of Applied Social

Psychology, 27(10), 864-876.

Nass, C., Moon, Y., Morkes, J., Kim, E.Y., & Fogg, B. J.

(1997). Computers are Social Actors: A Review of Current

Research. In B. Friedman (Ed.), Moral and Ethical Issues

in Human-Computer Interaction. Stanford, C.A.: CSLI

Press.

Peterson, B., & Ramierez, M. (1971). Real, Ideal-Self

Disparity in Negro and Mexican-American Children.

Psychology, 8, 22-26.

Romer, N., & Cherry, D. (1980). Ethnic and Social Class

differences in Children's Sex-role Concepts. Sex Roles, 6,

246-263.

Rosen, B., & Jerdee, T. H. (1976). The Influence of Age

Stereotypes on Managerial Decisions. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 61, 428-432.

Rosenkrantz, P. S., Vogel, S. R., Bee, H., Broverman, I. K.,

& Broverman, D. M. (1968). Sex-role Stereotypes and Self

Concepts in College Students. Journal of Consulting and

Clinical Psychology, 32, 287-295.

Ruble, T. L. (1983). Sex Stereotypes. Sex Roles, 9, 397402.

Taylor, C. R., & Stern, B. B. (1997). Asian-Americans:

Television Advertising and the "Model Minority"

Stereotype. Journal of Advertising, 26(2), 47-61.

Tortoriello, T. R., Blatt, S. J., & DeWine, S. (1978).

Communication in the Organization - An Applied

Approach. New York, N.Y.: McGraw-Hill.

Wells, W. E., & Siegel, B. (1961). Stereotype Somatypes.

Psychological Review, 8, 78.

Yip, A. (1997, June 5-13). Remembering Vincent Chin.

Asian Week.