Healthy Aging for a Sustainable Workforce A Conference Report November 2009

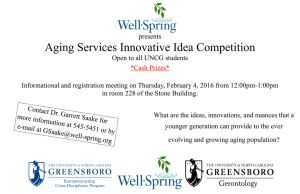

advertisement