S -B O H

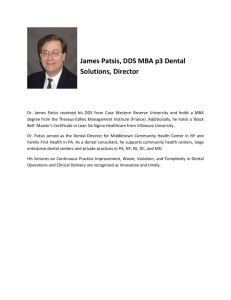

advertisement