PAl,

CREATIVITY, REPRESENTATIONALREDESCRIPTION,

INTENTIONALITY, MENTALLIFE:

An Emerging Picture

From: AAAI Technical Report SS-93-01. Compilation copyright © 1993, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved.

TERRY DARTNALLI

Computingand Information Technology

Griffith University

Nathan Qld 4111 Australia

Abstract. This paper outlines a general theory of creativity and locates the concept of creativity with respect to the

conceptsof thought, knowledgeand intentionality. Thepicture that I provide is outrageouslysimplified, but, as Dennett

said recently, such idealisation is the price we mustsometimespay for synoptic insight (Dennett 1992). I first provide

accountof a significant and central type of creativity. ThenI showthat there is independentempirical evidencethat we

are natively endowedwith this kind of creativity. Theemergingpicture throws light on what it is to have a mental life,

and on what it is for a representation to meansomethingto a system. This in turn gives a broader perspective, including

a general theory of creativity that, on the one hand, distinguishes betweencreative and non-creative systems,and, on the

other, accounts for individual differences betweencreative systems.

Thepaperis structuredas follows.Section1 arguesthat a

significantandcentraltypeof creativityis the ability to ’break

out’ of a mleset, or out of someother constrainingframework

of ideas. Section2 looksat ’breakingout’ in moredetail. We

break out whenweaccess certain representations in such a

waythat wecan reflect uponand modifythem.Butthese are

not anyold representations. Theyare declarative structures

that expressthe proceduralknowledge

that hadhitherto driven

our behaviour.In articulating these structures weacquirea

mentallife throughdiscoveringwhatit is that weknow,think

and believe. The beaver knowshowto build a dam, but

it cannot access this procedural knowledgeand express it

as a declarative structure: it doesnot knowwhatit thinks,

andconsequentlyhas no thoughts. Thusthere is an intimate

relationshipbetweenbeingcreative andhavinga mentallife.

Section 3 turns to AnnetteKarmiloff-Smith’sRepresentational RedescriptionHypothesis(RRH)(Karmiloff-Smith

1986,1990,1991,forthcoming

a, forthcoming

b, et al.; Clark

& Kamiloff-Smith,forthcoming;Clark, forthcoming). The

RRH

is a theory of cognitive development

that tries to explain howthe humanmindgoes beyonddomain-specificconstraints. It maintainsthat weare endogeneously

drivento redescribeour implicit proceduralknowledge

as explicit declarative knowledge,

andto continueto redescribeour knowledge

in increasinglyabstract terms. Thusweare natively endowed

with the kind of creative ability outlinedin Sections1 and

2. This empiricalevidenceis independentof the earlier argument.Creativitythereforetakes centrestage in our efforts

to understandhumancognition, becausewehavegroundsfor

believingthat it is in our natures(and maybe uniqueto our

natures)to be creative.

Thispackageof creativeability, mentallife andnativeendowment

appearsto be morethan a coincidence,and wemight

II wish to thank AndyClark, Margaret Boden and others for

helpful discussionsof this paper.

73

wonderwhetherthere is a unifyingfactor that wehavemissed.

This hunchis spurredby the fact that wewouldbe surprised

to find that a creativesystemcouldnot, evenin principle,have

thoughts,or that a systemwitha mentallife couldnot, evenin

principle,be creative. If this is correct thenwehavethe following:(1) a system

is creativeif andonlyif it canredescribe,

(2) a systemis creativeif andonlyif it has thoughts;therefore

a systemhas thoughtsif andonlyif it can redescribe.Thought,

creativity andredescriptionbeginto emergeas facets of the

samething. Canwethrowlight on this?

In Sections4, 5 and61 suggestthat the missinglink is that

it is only throughredescriptionthat wecan have(genuinely.

intentional)mentalstates. I suggestthat weinitially acquire

intentionalstates by beingcausallysituated in the world.Initially wedo not haveaccessto these states, whichconstitute

our implicit knowledge.Later weredescribe this knowledge

in termsof explicit, accessiblestructures - that expressour

knowledge,

thoughtsandbeliefs.

Section7 returns us to creativity. This cannowbe seen as

the struggleto articulate whatit is to be (causallysituated)

in the world.Thebeaverstays on its plateau of behavioural

mastery,but wego beyondthis and transformour procedural

knowledge

into thoughtsandtheories that wecan reflect upon

and change.

This gives us a general theoryof creativity that consists

of a phylogeniccomponent,

distinguishingpeoplefromslugs

and Sun4s,and an ontogenetic component

that accountsfor

individualdifferencesin termsof our abilities to deployour

redescriptivepowers.Section8 suggeststhat rare individuals,

such as MozartandPicasso, mayhavedirect access to their

redescriptive powers.If machinelearning theorists can implementthis ability then machinesmaybecomemorecreative

than people.

1. Boden on ’Breaking Out’

MargaretBoden(1990, forthcoming)arguesthat creativity

the exploration andtransformationof conceptualspace--or

morecorrectly,

ofconceptual

spaces.

A conceptual

space

is

a spaceof structuresgenerable,that is, defined,bythe rules

of a generativesystem.Weexploresuch a space by studying

the structureswithinit, andwetransformit by modifying

the

rules of the systemto producedifferenttypesof structures.

Bodenarguesfor this by first consideringthe notionthat

creativity involvesthe novelcombinations

of old ideas. Creativity does involvenovelty, but Bodenobservesthat such

accounts do not tell us whichcombinationsare novel, nor

hownovel combinations can comeabout. Her main--and

related--criticismis that manycreativeideas not onlyd/d not

occur before, but could not have occuredbefore. Previous

thinking wastrappedin a framework,relative to whichnew

ideas wereimpossible.Consequently,creativity requires us

to ’think the impossible’,to haveideas that are impossible

in the present fiamework:weneedto ’break out’ of a conceptual space by changingthe rules that define it. Kekule,

for instance, brokeout of the spacedefinedby the rules of

nineteenth-centurychemistry, and openedup the newspace

of aromaticchemistry.

2. Breaking Out and Having a Mental Life

Let us look at a couple of cases of ’breakingout’. First,

supposethat youare a Newtonian

physicist whobelieves that

light travels in straight lines. Thereis nowa sensein which

it is unthinkable

for youthat light wavesshouldbend,since it

is logically impossiblefor Newtonian

physicsto be true and

for light wavesto bend:necessarily, /f the laws of Newtonlan physicsare true then light does not bend. Whilstyou

remainwithin the Newtonianframeworkyou are trapped by

this necessity.Or imaginethat youare followingthe rules of

Euclideangeometry.Withinthe frameworkdefined by these

rule, s it is logically impossiblefor the sumof the anglesof

a triangle to be other than 180 degrees. Wecan break out

of these frameworks

by representingthe rules to ourselves.

Oncewehavedoneso wewill see that the necessity lies in

the hypothetical’lfthese rules thenX’--notin Xitself.

This showsus howweare limited by the assumptionsthat

wemake,but it does not explain whywefind it so hard to

articulate the assumptions.

I suggestthat wecanthrowlight on

this by distinguishingbetweenrule users andrule followers.

Rulefollowers are subject to rules. Theydo whatthe rules

say. Computerprogramsfollow rules whenweset themthe

task of (say) generatingproofs in Euclideangeometry.Rule

users, onthe other hand,canaccessthe rules as a declarative

structure.

Sometimesweare rule followers--whenwe follow the

rules of grammar,for instance--and weare trapped to the

extent that weare merelyfollowers. Webreak out whenwe

becomeusers--whenwearticulate the knowledge

implicit in

the rules wehad beenfollowing.

74

Wecan cast light on this by imagining

a ’cognitiveladder’.

Atthe bottomof the ladderare marshflies,hoverfliesandants.

Themarshflyis exasperatinglypersistent andfollowsus about

despiteour attemptsto swatit away.Hoverfliesmeetandmate

in midair. Antsexhibit apparentlycomplexbehaviour.These

creatures, however,havelittle or no knowledge,

either proceduralor declarative.Theirbehaviouris principally driven

by information

that is in the environment,

not in the organism

(Dreyfus1979). Themarshflyfollowsthe carbondioxidethat

weemit. Hoverfliesare hardwiredto transforma specific signal into a specific muscularresponse(Boden1990). Antscan

detect contours,andhaveroutinesfor selectingthe mostlevel

path (Simon1969; see discussions in Pylyshyn1979/1981,

Winograd

1981; also Dreyfus&Dreyfus1987.)

Whenwe discover these things we should abandonany

suspicionsthat wemighthavehad aboutthese creatures having a mentallife. Theyare not merelymindless:they have

no knowledge

worth speakingabout. Theyare not evenrule

followers.

Midway

up the ladder is the beaver. It has structured,

proceduralknowledge

about howto build a dam.However,it

has no accessto this knowledge.

It is trappedin a procedural

framework,

doingwhatits rules tell it to: first you put in

stones, then youput in big logs, then youput in smallones.

If a stormsweepsawaythe smalllogs, the beaverdemolishes

what’s left of the damand starts again. (This maynot be

empiricallytrue of beavers--if it is not, run the argument

witha morestupidcreature.)In this respectthe beaveris like

a computer

program:it is a rule followerrather than a rule

user. It doesnot representthe rules as an accessiblestructure.

If it didit wouldbe able to directlyaccessthe rule for putting

smalllogs on top of big ones.

Nordoesthe beaverhaveanythoughts. Wesee it scurrying

about trying to put the log there. The log keeps slipping

out, and the beaver keepsputting it back. Wewantto say

that the beaverthinks that the log shouMgo there--but we

do not wantsay that it has the thought’the log shouldgo

there’. This is a distinction that wecommonly

drawwith

people:the tennis playeris ’thinkingwhatshe’s doing’when

she plays intelligently, but this doesnot meanthat she has

explicit thoughtsaboutwhatshe is doing.

(Adrian Cummins

(1990) drawsa similar distinction

tweenthoughtsthat have, or do not have, conceptualcontent.

If Jo believesthat Bill is a bachelor,thenJo has graspedthe

concept’bachelor’.But whenwesay that Fido’believesthat

the noise (or the scent) comesfrom the south’, wedo not

believe that Fido has graspedthe concept’south’! Cummins

believesthat Fidohas no structuredor contentfulthoughts.I

believethat he has nothoughtsat all.)

Wetie these facts together whenwesay that the beaver

’doesn’tknowwhatit thinks’. It thinksthat the log shouldgo

there, but it doesn’tknowthat it thinksthis. It doesnot have

accessto its proceduralknowledge.

Nowconsider Le Penseur (Rodin’s sculpture of someone

engagedin deep thought--head bent, browfurrowed). Le

Penseur’shumanequivalent has thoughtsby virtue of being

able to expresshis knowledge

as a declarativestructure, reflect uponit, andchangeit if necessary.In doingthis he is

exercisingan ability that all of us have.

Enterthe empiricalevidence--thatweare natively endowed

to re, describeour proceduralknowledge

as declarativeknowledge(and to continueto redescribeit at increasinglyabstract

levels). Weare endogenously

driven to go from being rule

followersto rule users, thereby’breakingout’ in the sense

described.

3. Representational Redescription

this transcendencecomethoughtsand the mentallife. And

there is independentevidencethat weare natively endowed

withsuchan ability.

Weare boundto ask more. Weare boundto ask whether

it is only redescriberswhoare creative and whohavemental

lives. In the nextsectionI arguethat this is indeedthe case,

since our declarativestructurescanonly be aboutanythingif

they are groundedin implicit knowledge

broughtaboutby our

beingcausallysituated in the world,andare thenredescribed

as accessiblestructures.

4. Intentionality

TheRRHis a theory of cognitive developmentproposedby

AnnetteKarmiloff-Smiththat tries to accountfor the way

in whichthe humanmindgoes beyonddomain-specificconstraints. It maintainsthat the mindis endogenously

drivento

go beyondbehaviouralmasteryandto represent its knowledge

to itself in increasingly

abstractforms.It doesthis, as it were,

under its ownsteam--withoutneed of exogenouspressure.

Initially, the system’sknowledge

is embedded

in procedures.

It is implicitin the system’s

abilities. It is notavailableto other

procedures,nor to the systemas a whole.As Karmiloff-Smith

putsit, it is in the system,but notavailableto the system.Later

the systemredescribesit as declarative knowledge,

whichis

available to other procedures.Thesystemcontinuesto redescribeits knowledge

on increasinglyabstract levels, all of

whichare retained and maybe accessed whennecessary.

Themostcommonly

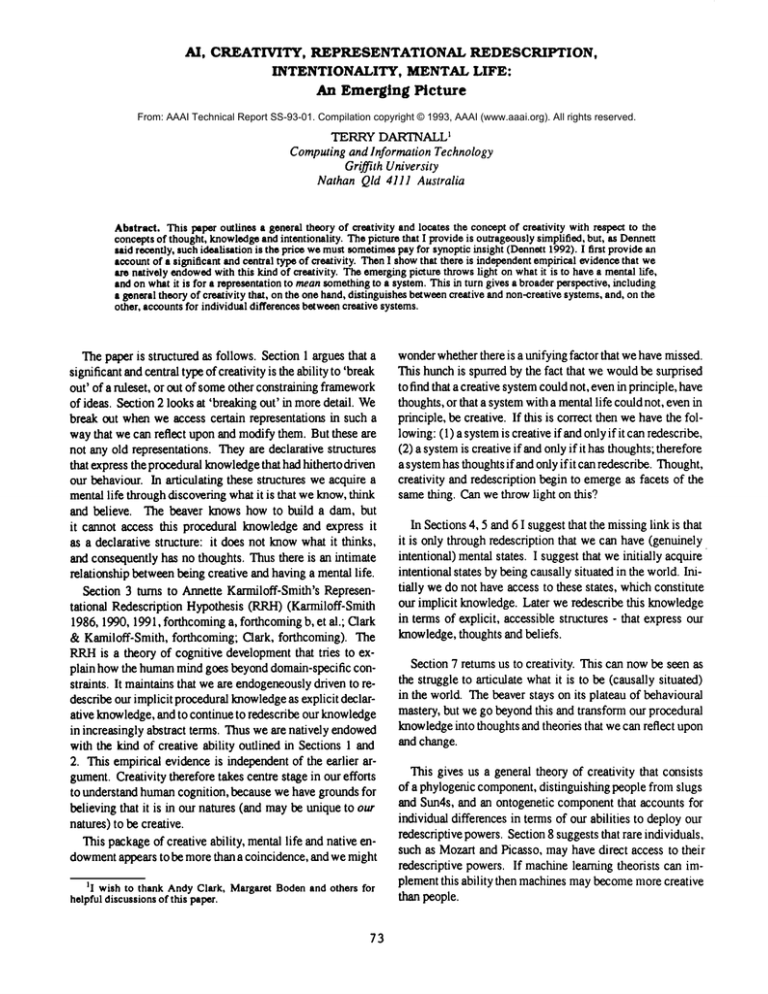

cited evidencefor this is the ’funny

men’pictures(see FigureI).

Westart with a groupthat has achievedmasteryof a task.

Childrenbetweenthe ages of four and six, for instance, are

able to drawhousesand stick figures of people. But when

they are asked to drawa funny manor a funny house, they

can do very little. Theyare lockedinto their house-drawing

or man-drawing

procedures:first youdrawthe head, then you

drawthe body, then you drawthe legs etc. To begin with

they can only modifyparts of the procedure,suchas drawing

a squarehead. Butslowlythey acquirethe ability to access

the proceduresas declarative structures, whereupon

they can

apply the rules in any order they wish. Children between

eight andten are quite fluent at this, andcan drawhandson

the end of legs and feet on the end of arms. Theycan even

mixprocedurestogether, and drawcentaurs, andheads that

have windows.

’But’, you mightsay, ’the youngerchildren could have

donethings like that--it just didn’t occurto themto doso’.

Tomeetthis objection, Karmiloff-Smith

askedthe 4-6 yearolds to drawa manwith two heads. Commonly,

the children

drewa man,drewa secondhead, and then went on to drawa

secondbody-and-legs:they werelocked into a man-drawing

procedure.

Theplot so far is this. Acentralandsignificanttypeof creativity is the ability to breakout of a ruleset, to gofrombeing

subjectto rules to beingable to articulate anduse them.With

75

and Redeseription

Theproblemof intentionality is the problemof howmental

states, symbolstructuresor artifacts canbe aboutanything.I

havearguedthat a systemis creativeif andonlyif it canaccess

its knowledge

structures. Butwhatis it for a structureto rapresent knowledgefor a system?Thestandard computational

accountis that the structure is in the mind’s’knowledge

bin’

or "thoughtbin" andthat the mindmanipulatesit according

to formal rules (Dennett1986calls this "HighChurchComputationalism";see also Richardson1981,Fodor1987). The

Knowledge

RepresentationHypothesis(see esp. Brian Smith

1985)says that a systemcontainsknowledge

if andonly if it

containsa syntactic structure that meanssomething

to us, and

that causesthe systemto behavein an appropriateway.E.g.,

the systemknowsthat tigers bite if andonlyif it containsa

structuresuchas ’Tigersbite’ that causesit to get up trees in

the presenceof tigers.

It is not clear howlocatinga structure withina systemcan

enableit to knowwhatthe structure means.Andunderstanding a sentencesurelyinvolvesmorethanbeingpropelledbyits

morphology.

Ratherthan pursuingthese points I shall outline

an accountof intentionalitythat gives a majorrole to representationalredescription,andthat throwslight oncreativity.

5. The InformationTheoretic Accountof

Intentionality

Myaccount is based on the InformationTheoretic account

of intentionality. This is most commonly

associated with

Fred Dretske, though John Heil and K.M.Sayre have developedtheir ownversions (Dretske1980,1981,Heil 1983,

Sayre1986). TheInformationTheoreticaccountexploits the

mathematicaltheory of informationadvancedby Shannonand

Weaver,whichsays that one state carries informationabout

anotherjust to the degreethat it is lawfullydependent

onthat

other state. Dretskerealisedthat this shedslight onintentionality, since "Anyphysicalsystem,then, whoseintemalstates

are lawfullydependent,in somestatistically significant way,

on the valueof an externalmagnitude..,qualifiesas an intentional system."(1980,p 286). Thusaboutnessis not a unique

featureof mentalstates but is foundin all causalrelationships.

Now,however,Dretskefaces the problemof cognitive error (of howwecan havefalse beliefs, etc). Hemaintainsthat

informationis distorted by the cognitivesystem.His critics

reply that this commits

himto sayingthat wecan gain knowl-

~- Joou~,4.11

- Jed. 8.7

p~- Viki 8. 7

~- ovy 9. 6

- PkillpPo 5. 11

-He*,,k. 8. 10

H - Lee 8, 6

- Nlcoio 9. 4

-Ovy 9. g

AA-PITII 6. 3

G-ANNA6. 6

~A-OlTTIAH

10.2

~-VOki 8. 7

A-JOSNUA

8. 8

Fig.I.

A- VAI.SgInl9. 0

R-Soey,, 10. 9

O~- Jv,oi, 10. 11

edgeby removingthe errors fromour cognitivesystems.This

implies that cognitive systemsmerelydistort information-andthis runs counterto our belief that morecomplex

systems

can gathermoreandbetter information.I shall return to this.

were,have’prime’intentionality--intentionality

that is dueto

direct causal influence.Genuinerepresentationsare grounded

by virtue of the system’beingin the world’.

Areall genuinerepresenters re, describers?Considerthe

beaver on the one hand, and a Sun4on the other. TheSun4

6. Combining Accounts

contains datastmcturesbut has no mentalstates. Its datastructures donot haveanyintentionalityfor it, donot express

Let us run the story with a redescriber. Theredescriber is

knowledge

for it, do not ’meananythingto it’. Let us supplaced in the world. Its peripheries are bombarded.It deposethat this is becausetheyare not redescriptionsof prime

velopsinternal states that constitnteprocedural

knowledge:

it

intentionality. Thebeaver(certainly the marshfly)is at the

can build dams,drawpictures, pronouncewords,etc. This is

knowledge

in the systemthat is not availableto the system. other extreme.It has primeintentionality, but doesn’tknow

whatit thinks. Let us supposethat this is becauseit hasn’t

It consistsin the systembeingin a certain state. Because

this

redescribedits knowledge

into accessible structures. Given

state wascausally determinedby the worldin a lawlike way,

these assumptions,the Sun4and the beaverhave no mental

it is knowledge

aboutthe world.

life becausethey are not redescribers. If havingno mental

ConsiderNETtalk.Whenit is bombardedwith phonemes,

life is alwaysdueto oneof these twoimpediments,

then only

NETtalkdevelopsintemal states that are about phonemes.It

redescribers havea mentallife. (Kant said that "concepts

settles into internal states that (to use Dretske’swords)are

without percepts are empty,percepts without concepts are

"lawfullydependent,in [a] statistically significant way,on

blind". Wemightsay that ’ungroundedrepresentations are

the value of an extemalmagnitude".Thesestates account

empty,primestates are blind’.)

for its ability to pronouncewords.Of course, it requires,

This, however,only restates the problem.Consequently

I

e.g., cluster-analysisto identifythe states that it has settled

shall

resort

to

an

onus

of

proof

argument--sometimes

referred

into, so that, as ClarkandKarmiloff-Smith

(forthcoming)say,

to as ’the best badargument

in philosophy’.Let us assumethat

the states are not available to NETtalk.Theyare only just

(despite somecontemporary

philosophicalopinions)wereally

availableto us!

do havementalstates. Theseare intentionalstates. Now,what

Wecan provide a straightforwardlycausal accountof the

groundshavewegot for thinkingthat intentional states can

intentionality of such a system.Moreover,its knowledge

is

arise in anywayother thanthroughcausalstimulationfromthe

relativelyundistorted,sinceits intemalstate is a direct reflecenvironment?If wehave no groundsthen wemust believe

tion of its environment.

Onthe other hand,this knowledge

is

that this is howintentional states comeabout in us. The

limited,inflexibleandinaccessible.

RRH

thentells its redescriptivestory. Surelythe point about

Backto our re, describer. Theredescribernowredescribes

beinga physicalsymbolsystem,rather thana virtual one, is

its implicit knowledge

as explicit knowledge--as

knowledge

that it can causallyacquireintentional states. Then,if the

availableto the system.Thisis aboutthe worldbecauseit is a

architectureis right, it canredescribethe knowledge

implicit

redescriptionof knowledge

that cameabout by beingsituated

in these states in termsof explicit symbolicrepresentations.

in the world.Its intentionalitylies in its pedigree.

Cognitivescientists andmachine

learningtheorists mustshow

Withredescriptioncomesrisk andthe possibility of cogni- us howthis is done.

tive error, whichis the price that wepayfor increasedabstraction, flexibility andan improved

ability to gatherinformation.

7. A GeneralTheoryof Creativity

This resolvesDretske’sproblemof howcognitivesystemscan

Wenowhavethe rudimentsof a general theoryof creativity.

apparently go wrong.Theydo not go wrong--butthere is a

trade-off betweenrisk and flexibility. (MargaretBodenhas Sucha theory contains a phylogeniccomponentand on onpointedoutto methat skills andabilities are fallible as well-- togenetic component.The phylogenic componentconcems

see her chapter on Hoverflies and Humansin Boden1990. the difference betweencreative systems(suchas people)and

Hoverfliescan missoneanotherin mid-air. Beaverscan build non-creativesystems(suchas slugs andSun4s).Theontogeis concernedwith individual differencesin

faulty damsby putting in the smalllogs first. Thepoint I am netic component

the

ability

to

redescribe.

making

is that at least someof the fallibility that is associated

Thephylogeniccomponent

locates creativity at whatClark

withhighercognitivesystems---e.g,false belief--is a natural

(forthcoming)

call "a genuinejoint in the

consequence

of re, describingour knowledge

in increasingly &Karmiloff-Smith

natural order". Oneof the great evolutionarydividesappears

abstract terms.)

Thusredescribers can acquire intentional states and gain to be betweensystemsthat can redescribe their procedural

knowledge

as accessible structures, and that havethoughts

knowledgethrough being situated in the world. Theythen

redescribe this knowledgein terms of accessible, modifi- anda mentallife, andsystemsthat cannotanddo not.

Nowlook at ontogeny.Thechild redescribesits procedural

able structures that constitute genuinerepresentations,such

as thoughtsand beliefs. Theyare genuinerepresentations, knowledge

as declarative knowledge.Hereontogenyrecapitmoreover,becausethey are redescriptions. Theyhaveinten- ulates phylogeny.Wethen continueto update our framework

tionality becausetheyare redescriptionsof states that, as it

of beliefs, strugglingto giveexpressionto whatit is to be

77

causallysituated in the world.

Of course, such frameworksare not everywheregrounded

in re, description. Theyare only groundedas a whole.Quine

andDavidson

talk abouta looselygrounded

webof belief. The

RRH

says that there are layers of (re)description, grounded

(if myaccountis correct) in the bottomlayer of primeintentionality. Nolayers are lost or destroyed,andall can be

accessed.Andour articulatedbeliefs, as well as a fluctuating

environment,cause us to continually restructure andupdate

the framework.

This is mostobviousin the Arts. Art tries to expresswhat

weknowor believebyarticulatingit as a declarativestructure:

Munch’sScream,El Greco’sRevelation of St John, Bach’s

Passions,Owen’swarpoetry--all articulate by extemalising.

Wesometimessay that we do not knowwhat we believe

until wehavewritten it down.In writing Sons and Lovers

D.H. Lawrence

articulated his complex

attitude to his parents,

that haddrivenhimto regardhis father as a despotandtyrant.

Havingvoiced his attitude he wasable to evaluate it and

changeit. "Weshedour sicknessesin books,"he said.

Thetheoryof redescriptionexplainswhatis goingon here,

andshowswhyit is creative. Redescriptiondoesnot give expressionto beliefs that werealreadythere: it actuallybrings

theminto existence.Hithertowebelievedthat.., suchandsuch

(just as the beaverbelievesthat the log shouldgo there, but

doesnot havethe thought’the log shouldgo there’). Wewere

in states that droveour behaviour.Redescriptionexpresses

the dispositionsinherentin these states as accessiblerepresentations. Thisis not creatingsomething

out of nothing--but

it is the nextbestthing.

This resolves an apparentproblemwith Boden’saccount.

Thereis, I think, a dangerof her accountbeggingthe question by sayingthat routinecreativity is the creativesearchof

conceptual

space(or the searchof a limited,’creative’space).

Since generative rules only determinewellformedness,we

need to knowwhyMozartwas consistently moresuccessful

(that is, morecreative) in searchingthroughthe musicalspace

of his daythanSalieri was.

I suggestthat the answerlies in distinguishing between

three kinds of art. The first merely explores a space of

structures--say, musicalstructures. Wemightbe inclined

to regardthis as little morethana technicalexercise.Atthe

otherextremewehaveart that breaksout of the confinesof the

genre.Thethird kind remainswithinthe genre, but breaksout

of anotherspaceby givingvoiceto feelingsandattitudes that

hadnot beenvoicedbefore,either by the individualor at all

(Boden’sdistinction betweenP-creativityandH-creativity).

8. Are there TwoTypesof CreativeAbility?

developinghis figure-drawing programAARON,

Harold Cohenfoundit necessaryto continuallyextemaliseandevaluate

AARON’s

ability, in order to find out whatits procedural

knowledgeenabledit to do. Edmonds

(forthcoming)quotes

himas saying"weextemalisein order to find out whatit is

that wehavein our heads... It is throughthis extemalising

process that weare able to knowwhatwebelieve about the

world"(Cohen,1983;see also McCorduck,

1991).

A fewrare individuals, however,seemto create with consumateease. Mozartsaid that he wouldexperience a composition all at once--in a moment--both

before andafter he

wroteit down:"Aah,whata feast is there" he said. Wemay

he sceptical, but the manuscriptscontainno errors. Thereis

no apperceptiveagonisinghere, no evidenceof an extemalisation/evaluation

cycle. Picasso,too, wasunableto put a foot

wrong:"I do not seek--I find", he said. MozartandPicasso

seemto havedirectly and unproblemmaticaUy

achievedwhat

the rest of us blindlystrugglefor. Mozart’s

talk aboutinstantaneousnesssuggeststhat he haddirect andspontaneousaccess

to a declarativestructure. In ’A Conversation

withEinstein’s

Brain’the tortoise/DougHofstadterinvites us to imaginewhat

it wouldbe like to experiencea pieceof musicinstantaneously

bylookingat the side of a long-playingrecord:"since all of

the musicis on the face of the record,whydon’tyoutake it in

at a glance,or at mosta cursoryonce-over?

It wouldcertainly

provide a muchmoreintense pleasure". And"Why

don’t you

paste all the pagesof the writtenscoreof someselectionupon

your wall and regard its beauties fromtime to time, as you

woulda painting?.., insteadof wastinga full hourlistening

to a Beethovensymphony,on wakingup someroomingyou

couldsimplyopenyoureyes andtake it all in, hangingthere

on the wall, in ten secondsor less, andbe refreshedandready

for a fine, fulfilling day?"(Hofstadter1981).

Wasit like this for Mozart?(Remember

that he claimsto

r) The

haveexperiencedit all at oncebeforehe wroteit down.

RRH

saysthat wehavethe ability to spontaneously

redescribe,

so perhapsMozarthad(almost?)full controlof this ability.

If so, there are twotypes of creativity ability. Thefirst

involves the extemalisation/evaluationcycle: weconstruct

theories aboutour abilities by observingthemin action. The

secondrests on the fact that abilities are grounded

in states.

Balls are able to bouncebecauseof their molecularstructure.

NETtalk

is able to pronounce

wordsbecauseit has settled into

a subsymbolic

state. Ourabilities are similarly groundedin

states. Nowsupposethat wecan redescribe the knowledge

that is implicit in these states. Thenwewouldno longer

needto construct theories about whatweknowand believe

by observing our actions. TheRRHtells us that wehave

exactlythis ability. Mozart,it seems,wasespeciallygoodat

exercising

it.

For mostof us the creative process is a slow and painful

one. Weengagein a cycle of extemalisation and evalua9. Conclusion

tion, in whichweexternalisesomething,

evaluateit, readjust

our goals, and repeat the process (Edmonds,forthcoming; TheRRH

is a philosopher’sstone for creativity research: it

Sharpies, forthcoming).Attemptsto producecomputerisad solves problems,generatesplausibleexplanations,andleaps

art and computer-assistedart havefoundprecisely this. In

mightybuildingsat a single bound.Wepay a price for this:

78

the belief that the mindis endogenously

drivento spontaneouslyredescribe--thatto someextent human

knowledge,

like the objective knowledge

of Hegel’sOvermind

or Absolute, ’evolvesunderits ownsteam’.Thisphraseis Pepper’s

(1972),whovigorouslyobjectsto the notion.Theclaim,however, is nowan empiricalone. Assuming

that the dataand

analysisof human

cognitionare correct,cognitivescientists

andmachine

learningtheoristsmustnowtry to implement

this

ability.

References

Bodcm,M.A.: 1990, The Creative Mind, Myths and Mechanisms,

Weidenfeld& Nicolson, London.Revised edition, 1992, Cardinal, London.

Boden, M.A.: forthcoming, Creativity and Computers, in Dartnall,T. H., forthcoming.

Clark, A.C. & Karmiloff-Smith, A.: forthcoming, The Cognizer’s

Innards, Mind and Language.

Clark, A.C.: forthcoming, Creativity and Cognitive Development,

/n Dartnall, T. H., forthcoming.

Cohen,H.: 1983, Catalogue. Tate Gallery. Cited in Edmonds,E.,

forthcoming.

Cummins,A.: 1990, The Connectionist Construction of Concepts,

/n Boden,M.A. (ed.) The Philosophyof Artificial Intelligence,

Oxford.

Dannall, T.H.: forthcoming,Artificial Intelligence and Creativity,

KluwerAcademicPublishers, Dordrecht.

Denned, D.: 1986, The Logical Geographyof Computational Approaches: A ViewFromthe East Pole, in Brand, M. &Harnish,

R. M. (eds,) The Representation of Knowledgeand Belief, University of ArizonaPress, Tucson.

Denned, D.: 1992, Commandosof the Word, Times Higher Edw

cation Supplement, 27/3/92.

Dretske, F.: 1980, TheIntentionality of Cognitive States, MMwest

Studies in Philosophy,5.

Dretske, F.: 1981, Knowledge and the Flow of Information,

MIT/Bradford, Cambridge Mass.

Dreyfus, H.L.: 1979, What Computers Can’t Do: The Limits of

Artificial Intelligence, 2nd ed., Harperand Row,NewYork.

Dreyfus, H.L. & Dreyfus, S.E.: 1987, Mind Over Machine. The

Power of HumanIntuition and Expertise in the Era of the

Computer, The Free Press, NewYork.

Edmonds,E.: forthcoming, Cybernetic Serendipity Revisited, in

Dartnall,T. H. (forthcoming).

Fodor, J.: 1987, Psychosemantics:The Problemof Meaningin the

Philosophy of Mind, MITPress, Cambridge, MA.

Heil, J.: 1983, Perception and Cognition, University of California

Press, Berkeley.

Hofstedter, D.R.: 1981, A Conversationwith Einstein’s Brain, in

Hofstadter, D. R. and DonneR,D.C. (eds) The Mind’s I, Basic

Books, NewYork.

Karmiloff-Smith, A.: 1986, From metaprocess to conscious access: evidencefrom children’s metalinguistic and repair data,

Cognition,2: 3.

Karmiloff-Smith, A.: 1990, Constraints on representational

change: evidence from children’s drawing, Cognition, 34.

Karmiloff-Smith, A.: 1991,BeyondModularity:Innate constraints

and developmentalchange, in Carey, S. and Gelman,R. (eds),

Epigenesis of the Mind: Essays in Biology and Knowledge,

Laurence ErlbaumAssociates.

Karmiloff-Smith, A.: forthcoming, a, Beyond Modularity: a developmental perspective on cognitive science, MIT/Bradford,

Cambridge Mass.

79

Karrniloff-Smith, A.: forthcoming, b, PDP:Preposterous Developmental Postulates7 ConnectionScience.

McCorduck,P.: 1991,Aaron’sCode, W.H. Freeman and Company,

NewYork.

Popper, K.R.: 1972, Objective Knowledge: An Evolutionary Approach, ClarendonPress, Oxford.

Pylyshyn, Z.W.: 1979181,Complexityand the Study of Artificial

and HumanIntelligence, in Ringle, M.(ed.) PhilosophicalPerspectives in Artificial Intelligence, HumanitiesPress, Atlantic

Highlands, NJ.

Richardson, R.C.: 1981, Internal Representation: Prologue to a

Theoryof Intentionality, PhilosophicalTopics, 12.

Sayre, K.M.: 1986, Intentionality and Information Processing:

AnAlternative Modelfor Cognitive Science, Behavioural and

Brain Sciences, 9.

Sharpies, M.: forthcoming, ComputerSupport for Creativity, in

Dartnall, T. H., forthcoming.

Simon, H.A.: 1969, The Sciences of the Artificial, MIT Press,

Cambridge.

Smith, B.: 1985, Prologue to ’Reflection and Semanticsin a Procedural Language’, in Brachman,R. and Levesque, H. (eds),

Readings in Knowledge Representation, Morgan Kaufmann,

Los Altos, California.

Winograd, T.: 1981, WhatDoes it Meanto Understand Language?,

in Norman,D. (ed.), Perspectives on Cognitive Science, Ablex,

NJ.