On a "Common

Language"for a "Best Practices"

Daniel E. O’Leary

University of Southern California

3660 Trousdale Parkway

Los Angeles, CA90089-1421

Oleary@rcf.usc.edu

From: AAAI Technical Report WS-99-13. Compilation copyright © 1999, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved.

Abstract

firms, this is probably not a problemunless the dictator

changes (e.g., through executive turnover) or there is

attempt to implement the commonlanguages in some

other setting (e.g., sell the best practices knowledge

base).

Knowledgemanagementsystems are becomingembedded

in knowledge work. As part of those knowledge

management

systems, increasingly, firms are developing

best practices knowledgebases that summarizea wide

rangeof enterprise processes.Central to those particular

knowledgebases are common

languagesused to facilitate

access and navigation through the knowledgebase. This

paper summarizes

someof the evidenceas to the necessity

of common

languagesin best practices databases. Further,

somebarriers standing in the wayof development

and use

of these common

languagesare summarized.In addition,

this paper developsa modelfinding it is "impossible"to

rationally choosea common

languagethat meets needs of

all individualsandthe firm, unlessdictatorshipis allowed.

Scope

Consulting firms, such as the "big six" have developed

best practices knowledgebases for their owninternal

direct use. Arthur Andersen and Price Waterhouse

apparently were amongthe first such developers. Each of

these firms have publicly available materials regarding

their best practices knowledge bases (Arthur Andersen

1997, APQC 1997, International

Benchmarking

Clearinghouse 1997, Price Waterhouse 1995 and 1997).

Asa result, the descriptive scopeof this paper is primarily

limited to information available from those sources.

1. Introduction

Increasingly, firms are developing"best practices"

knowledgebases as part of their knowledgemanagement

systems. Best practices (or leading practices) knowledge

bases provide access to enterprise processes that appear to

define the best waysof doing things. At the base of these

best practices knowledgebases is what the developers

(e.g., Price Waterhouse,1997) call a "common

language"

or (International BenchmarkingClearinghouse 1997)

"commonvocabulary."

2. Best Practices KnowledgeBases

Best practices knowledgebases capture information and

knowledge about the best way to do things. Best

practices knowledgebases have found use in a wide range

of enterprises.

For example, as noted by Davenport

(1997), General Motors- HughesElectronics capture best

process reengineering practices in a database. In addition,

major consulting firms, including Arthur Andersen and

Price Waterhouse, have developed best practices

knowledgebases.

The purpose of this paper is to summarize the use of

commonlanguages in best practice knowledgebases and

present an analytic model of the choice of common

language concepts that are included in or excluded from

the commonlanguage. This paper finds that based on a

small set of assumptionsit is "impossible" to rationally

choose a commonlanguage that will be optimal for

individual membersof a group and the group itself, unless

"dictatorship" is allowed. Thus, the resulting common

languages are likely to meet the needs of the dictator or

the needs that the dictator sees are important for the

organization. Since the organizations that have developed

best practices knowledgebases typically are for-profit

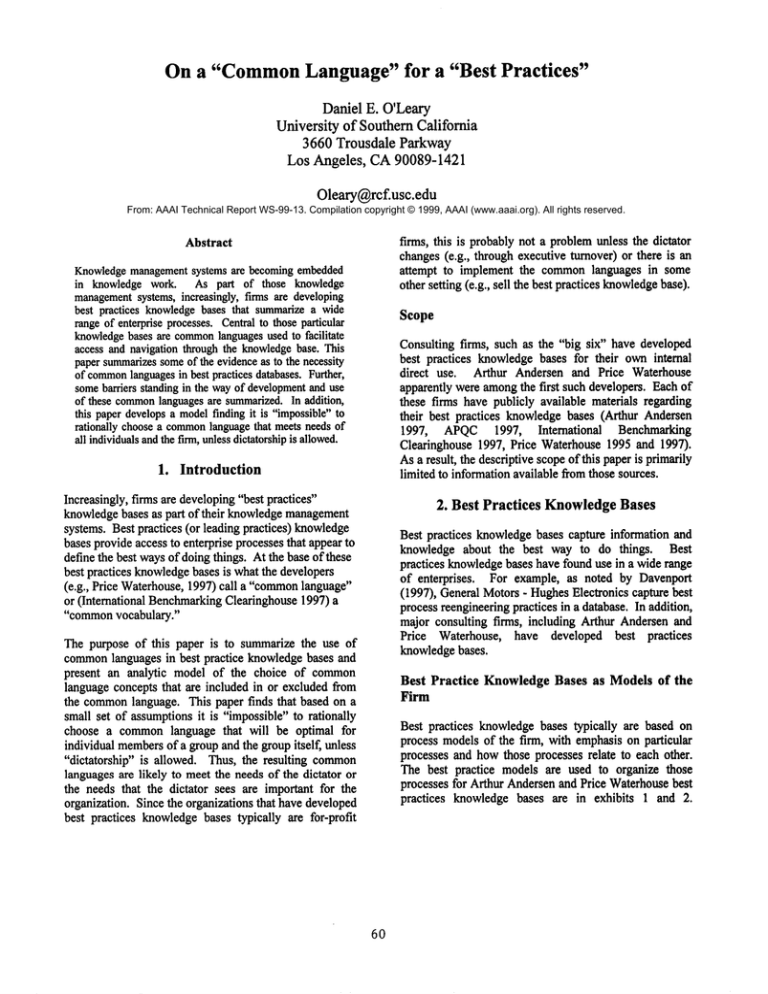

Best Practice

Firm

Knowledge Bases as Models of the

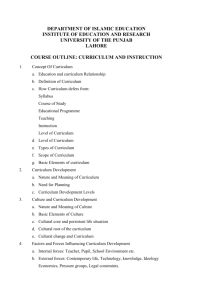

Best practices knowledge bases typically are based on

process models of the firm, with emphasis on particular

processes and howthose processes relate to each other.

The best practice models are used to organize those

processes for Arthur Andersenand Price Waterhousebest

practices knowledge bases are in exhibits 1 and 2.

60

Exhibit1 -- ArthurAndersen

¯ Understandl I 2. Develop I I 3. Design I I

4. Market

Markets& [---t

Customers

] [ Vision

Strategy& [-’t

] ] Products

ServicesM&

&Sell

5. Produce&l

Deliverfor

Manufaeturin

i

Organization

I

7. Invoice&I

Service

Customers

Deliverfor

Service

Organization

8. Develop and Manage HumanResources

I

9. ManageInformation

I

10. ManageFinancial and Physical Resources

]

I

I 1. Execute Environmental ManagementProgram

I

l

12. ManageExtrernal Relationships

I

[

13. ManageImprovement and Change

Global Best Practice

I

Classification

Scheme (Arthur

Andersen)

Exhibit2 -- Price Waterhouse

\

Perform

Logistics and/,~ Customer

Service

Distribution/

Poo\lo

Marketing and/,~ Products and/~ Products a

Sales / Services

/ Services

Perform Business Improvement

ManaEeEnvironmental Concerns

ManageExternal Re!at!onships

Manage

Corporate

Services

and Fa~

L

ManaE~Financials

Mana~ Human Resources

Provide Lesal Services

Perform Planning and Man*~ement

Perform Procurement

Develnn.

~¢zMaintain

gwt~q18,

andTot,h~,^l^~,_

.....

KnowledgeVlew Multi-Industry

Process Technology (Price Waterhouse)

Whatis in Best Practice KnowledgeBases?

maybe referenceto articles or otherdescriptionsof the

processes. Process measurements

are also summarized

providinga basis for benchmarking.

Somebest practices

knowledgebases include warstories, andinformation

relating processesandtechnologyenablerinformation.

Finally, the knowledgebase mayhave reference to

Best practice knowledge bases include a range of

materials. Typically they include text and or graphic

representationof best practice processes. Best processes

maybe generic or designedfor specific industries. There

61

particular experts on the processes.

with other Knowledgebase Languages?

What is the Relationship

Between Common

Languages and Knowledge ManagementOntologies?

The information describing the process provides a basis

for organization of the best processes. As a result, best

practices are organized by process, performance measure

benchmarks, industry-based process information and

technology enabler.

Are Best Practices

or External Use?

To what extent does a Best Practices KnowledgeBase

Require a CommonLanguage?

There is evidence that developers have found the need for

a common

language in the best practices databases to be a

critical issue. For example, as noted by Price Waterhouse

(1997)

Knowledge Bases for Internal

A CommonLanguage

It is almost impossible to make intelligent

comparisons without a commonset of reference point

to describe the key processes and core capabilities of

a business. Even within the same company,different

divisions cannot compareprocesses whenthey lack a

commonlanguage to describe what they do. The

challenge becomes even greater when executives

attempt to compare separate companies in the same

industry or across different industries. Best practices

must be accompanied by a commonlanguage that

breaks business processes into activities that all

companiesrecognize, understand and share.

Initially best practice knowledgebases were designed for

internal usage. Using best practice knowledge bases,

consultants and auditors could have access to the best

practices in order to help or understand their client’s

processes. Clients benefited indirectly through having

more knowledgeableauditors and consultants.

However, recently firms apparently have become

increasingly interested in direct access in order to

facilitate

"bench marking" with other firms and

improving their work processes. As a result, some

consulting firms have madetheir best practice knowledge

bases directly available to users. For example, Arthur

Anderson’s KnowledgeSpace (http://www.knowledgespace.corn) was made available as a service over the

internet to subscribers in 1998. (In addition to access to

best practices information, subscribers can access news,

and other resources.) As a result, clients can nowdirectly

access best practice information.

How are CommonLanguages Developed?

There is limited information available regarding how

these different commonlanguages have been developed

and how choice was made between alternative language

representations. It is assumedthat different groups that

will be using the commonlanguage are represented by an

individual who represents their interests. Within that

group choices are made regarding which concepts to

include and exclude, what to call particular concepts, etc.

The International

Benehmarking Clearinghouse

apparently madeheavy use of a single source of expertise

in order to develop their common

language.

Best Practice

Knowledge Bases are Part of a

Portfolio of Knowledge Bases

Typically, best practice knowledgebases are treated as a

standalone knowledge base. However, best practice

knowledge bases are only a part of the portfolio of

knowledge management system knowledge bases. In

consulting firms, those knowledge bases also include

proposal knowledgebases, engagement knowledgebases,

news, information and expertise databases and others.

The Center and Arthur Andersen & Co. have

collaborated

closely to bring the Process

Classification Frameworkto life and enhanceit over

the past three years. The center would like to

acknowledgethe staff of Arthur Andersen for their

research and numerousinsights during this effort.

(International BenchmarkingClearinghouse 1997)

3. Common

Languagesin Best Practices

KnowledgeBases

Best practice knowledgebases typically are organized

around a commonlanguage / taxonomy. The existence of

a commonlanguage for best practices knowledge bases

raises a numberof questions.

¯

To what extent does a Best Practices Knowledge

Base Require a CommonLanguage?

¯

Howare CommonLanguages Developed?

¯

How many Best Practice CommonLanguages are

there?

¯

Howdo Best Practice CommonLanguages Interface

How many Best Practice

there?

CommonLanguages are

It is unclear howmanydifferent best practice common

languages have been developed. However, to-date there

have been reports of a few large companies, such as

General Motors (e.g., Davenport 1997), and large

consultants (Arthur Andersen 1997 and Price Waterhouse

62

organization,knowledge

navigation, facilitation of cross

industry comparisons, need to eliminate "insider

terminology,"and the broad base of constituencies, some

of whichare discussedin moredetail here, whileall are

discussedin detail in a longerversionof this paper.

1995and 1997)each developingbest practices databases

and their owncorrespondingcommon

languages.

Which CommonLanguage is Optimal?

Withthe existence of all of these common

languages,

whichis best? Thefact that different common

languages

are emergingprobably is evidencethat developers have

different needsand as a result developdifferent common

languagesto meet those needs. However,there are some

apparent similarities. For example,two of the common

languages that have gotten the most publicity (Price

Waterhouse 1995 and International Benchmarking

Clearinghouse/ArthurAndersen1997) appear to be based

on a common

overall model,Porter’s value chain model

(Porter, 1980).

Knowledge Navigation

A commonlanguage facilitates knowledgenavigation

througha best practices database(ArthurAndersen1997).

Ourexperiencetaught us that the common

organizing

framework

wasvery valuable -- it providesus with a

common

and understandablewayto navigate through

the knowledge.

Cross Industry Usage

How do Best Practice

Common Languages

Interface with other Knowledgebase Languages?

Oneof the benefitsof best practicesis to be able to take a

processin one industry andadapt it to anotherindustry.

Apparently, a common

language can facilitate cross

industry comparisons

(Price Waterhouse

1997).

As a stand alone knowledgebase, best practice common

languagesgenerallydo not needto directly interface with

other knowledgebase languages.However,this is likely

to change as knowledgemanagementsystems become

increasinglyintegrated.

The challenge becomesevengreater whenexecutives

attempt to compareseparate companiesin the same

industryor acrossdifferent industries. Best practices

must be accompaniedby a commonlanguage that

breaks business processes into activities that all

companiesrecognize, understandand share.

What is the Relationship

Between Common

Languages

and Knowledge Management

Ontologies?

Issues relating to common

languagesin best practices

knowledge

basesare part of a larger set of issues referred

to as a knowledgemanagement

ontologies (KMOs).

Eliminates Needfor "Insider Terminology"

The International BenchmarkingClearinghouse (1997)

argued that a commonlanguage allows them to break

awayfrom specialized language. In particular, they

indicatedthat they

At the broadestlevel, an ontologyhas beendefinedas an

explicit specificationof a conceptualization

(e.g., Gruber,

1993). Within artificial intelligence, ontologies are

necessary for multiple independentcomputingagents to

communicate

withoutambiguity.In addition, in artificial

intelligence, ontologiesare the center of muchresearchon

reusability of knowledgebases. A KMO

is a knowledgebased specification that typically describes a taxonomy

that defines the knowledge. Within the context of

knowledge management systems, ontologies are

specifications of discourse in the form of a shared

vocabularyfor humanactors. Ontologiescan differ by

developerandindustry, dependingon their humanusers.

... were convincedthat a common

vocabulary, not

tied to any specific industry was necessary to

classify information by process and to help

companiestranscend the limitations of insider

terminology.

Broad Rangeof Constituencies

In addition, best practices knowledge

bases are designed

for a widerange of users for a widerange of uses. For

example,Price Waterhouse

(1995, p. 12) notes that "More

than 30,000... professionals worldwidehave access to

this tool for the purposeof collecting, refining, and

sharingtheir knowledge

with clients to help themenhance

organizational competitiveness." As noted by Price

Waterhouse,

(1995, p. 9)

4. Why is it Necessary to have a Common

Language?

Witheachof the reports of best practice knowledge

bases,

there is also discussion of the uniquecommon

language

used to access and organize the knowledgebase. The

need for a commonlanguage derives from a numberof

factors including, knowledge reuse, knowledge

Witha common

language to describe the processes

63

and activities of all companies,any companycan

compareitself to another. Price Waterhouse,The

Knowledge

Viewtaxonomy

earl serve as the basis for

best practice comparisons across industries,

languages, and time zones. In fact the taxonomyis

already being used on five continents and has been

translated into several worldlanguages.

TheFramework

does not list all processeswithin any

specific organization. Likewise, not every process

listed in the Frameworkis present in every

organization.

Howdo developers decide what should be included or

excluded? Howdo they choose betweendifferent terms

to be includedin their best practices knowledge

bases?

5. Barriers to a CommonLanguage in a Best

Practices Knowledge Base

Individual Differences

Eachof these barriers suggestthat different individuals

wouldhavedifferent preferences regarding the various

terms and concepts included in or excluded from the

common

language. For example, someusers mayprefer

informationcapturing industry-basedinformation,while

others wouldprefer a "generic"view. Asa result, evenif

there is a commonlanguage, there are likely to be

divergentneeds.

Theseindividual differences, and varyinglevels

of expertise suggest that firms wouldemploya broad

range of individuals in order to generate these common

languages. Accordingly,a modelof howthat group can

rationally makethe choices required for a common

languagewouldbe a helpful andimportantcontribution.

Althoughcommon

languagesare seen as necessary, there

are a number

of barriers to their implementation.

Common

Languages are Costly to Develop

Best practices knowledgebases are particularly complex

anddifficult to develop

... weunderestimatedthe sheer effort necessaryto

translate ... knowledgeabout best practice into

useful explicit knowledge.The central team could

not, on its ownextract ... knowledgeof the

consultantsand the professionalsin the field ....

After a significant effort, the teamhadproduceda

CD-ROM

with the classification scheme,but only

10 of the 170 processespopulated,andwith limited

information. The initial offering almost died an

early death--it seemedmucheffort for little

payoff.(ArthurAndersen,1997,p. 4)

6. A Model of Choosing a Common

Language

This section discusses a model of group choice of a

commonlanguage and vocabulary (Keeny and Raiffa

1993). Five rationality assumptionsare elicited and

methodis sought to satisfy those five assumptionsin

order to generate a rational approach to generate a

commonlanguage.

Generalvs. Specific Vocabulary

A commonlanguage forces all users into the same

vocabulary,so that users are unableto take advantageof

vocabularies that meet specific needs.

This is

unfortunate, since specific technical vocabularies are

typically developed because general language is

insufficient (e.g., Kuhn1970).

Notation

Let S = (a,b,c, ...) be the set of alternativesavailablefor

some concept in the framework. S is the set of

alternatives fromwhichthe choicewill be made.Let I.I

indicate eardinality. Let aRbindicate that onevocabulary

term a is preferredto or indifferent than someother term

b. R is used to stand for the preference relationships

betweenall a and b. For example,R earl be specified

througha utility function UwhereaRbif and only if U

(a) > U (b). Suppose that there are n individuals

responsible for deciding amongeach of the set of

alternatives. Eachindividualwill be treated as oneof the

participants in the set G, the groupmakingthe decision.

Eachmemberin G maybe representatives fromdifferent

subgroupswithin a company,as with Price Waterhouse

(1995, 1997) or from multiple companies, as in the

frameworkdevelopedby the International Benehmarking

Clearinghouse(1997). Each participant is assumed

Incorrect Usage of the Common

Language

Simplyhaving a common

languagedoes not ensure that

users knowhowto use that language. For example,as

noted by Kuhn(1970p. 204) "Totranslate a theory into

one’s ownlanguageis not to makeit one’s own." As a

result, there is potential to misusethe common

language

resulting in comparisons

that are not sensible.

Whatis included and what is excluded?

Commonlanguages make specific inclusion and

exclusion of particular concepts. For example,as noted

by the International Benchmarking

Clearinghouse(1997)

64

have preferences between the choices madefor the

common

language. For example,consulting and auditing

wouldlikely havedifferent preferences. Let P~ represent

the preferencerelationshipof participant j andFj be the

utility functionof participantj. Let aRabindicatethat the

groupas a wholeprefers a over b.

1970).Further, only dictatorships satisfy assumptionsAD.

Discussion

The only group choice method that meets Arrow’s

conditionsis "dictatorial choice." This wasa concernof

Arrowbecause of equity issues. As noted by Arrow

(1970,p. 86)

Assumption A (Complete Domain)

Assume

that n > 2, [Sl ~ 3, andaRabexists for all possible

aRjb. Thatis, there are at least twomembers

in the group,

they choosebetweenat least three alternative concepts

and a group order can be specified for all possible

individualorderings.

... the very act of establishinga dictator or elite to

decideon the social goodmaylead to a distortion of

the pragmatic from the moral imperative. "Power

always corrupts; and absolute power corrupts

absolutely"(LordAction).

AssumptionB (Positive Association of Social and

Individual Orderings)

For decisions that influence intra firm common

languagesfor best practices, there maybe no "equity"

issue. Ideally, common

languages wouldbe chosen to

maximizethe overall company

utility. That is not to say

that those whoestablish common

languagesalways will

always makeoptimal choices. In addition, within

companies,common

languagechoices are likely to leave

somedivisions or subgroupsas beneficiaries over other

divisions and subgroups. However, as soon as the

language is used outside of the organization of the

dictator, beyondthe boundsof the dictator, there can be

concern about the decisions that have been made.

Choicesmadethat met the needs of the dictator, maynot

meetthe needsof users in other organizations.

If aRobfor a set of individualratings, andif (1) cRib,

and c ~ a are not changed,(2) aRjband bRjaV b are not

changedor are modifiedin b’s favor, then aRab. This

says that if the groupprefers a to b andthe only changes

that occur amongindividuals is with someadditional

groupmembers

preferringa, then a is preferredover b.

Assumption C (Independence

Alternatives)

of Irrelevant

Anytwoset of the rankingsmusthaveidentical corporate

choicesin S or subsetsof S. In particular, a choicerule

has independence

of irrelevant alternatives if andonly if

aR6b(for a,b ~ S’, VS’ c_ S) impliesaRab(for a,b ~

If one or morealternatives are removedfrom the set of

choicesof concepts, then the choiceamongthe remaining

alternativesis identical to the original orderingfor those

alternatives.

7. Summary

This paper has investigated commonlanguages and

vocabulariesused in best practices knowledge

bases, also

referred to here as knowledgemanagement

ontologies.

The paper briefly discussed best practices knowledge

bases and the importance of commonlanguages.

Advantages and disadvantages of using common

languages were investigated in order to illustrate

divergent user needs. A model was developed to

understand the group decision process associated with

developinga common

language.

AssumptionD (Individual’s Sovereignty)

For eacha,b, 3 someset of individual orderingsaRjbsuch

that aRGb.Thatis, for eachpair of alternatives a andb,

there is someset of individual orderings such that the

groupprefers a to b.

References

AssumptionE (Nondietatorship)

Arrow,K. 1970. Social Choice and Individual Values,

YaleUniversityPress.

There does not exist somek ~ G, such that aRobif and

only if aRkb,Va,b~ S. Adictatorship wouldexist if one

person (or division or companyrepresented by that

person) determinedthe group’s common

language.

Arthur Andersen. 1997. "Knowledge, The Global

Currencyof the 21st Century."

Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem

APQC

- AmericanProductivity & Quality Center, 1997.

"Arthur Andersen"

There is no solution that meets assumptionsA-E. This

result is knownas Arrow’simpossibility theorem(Arrow

65

Bernstein, L. 1974. Financial Statement Analysis, Irwin,

Homewood,

Illinois.

Davenport,

T.,"Some Principles

of Knowledge

Management,http://knowman.bus.utexas.edu/kmprin.htm

Ernst & Young, 1997. Center for Business Knowledge,

"Leading Practices KnowledgeBase.

Gruber, T. 1993. "A Translational Approachto Portable

Ontologies," KnowledgeAcq, 5, 2, pp.199-220.

International

Benchmarking Clearinghouse 1997.

"Process Classification Framework."

Keeny, R. and Raiffa, H. 1993. Decisions with Multiple

Objectives, CambridgeUniversity Press

Kuhn,T. 1970. The Structure of Scientific Revolution,

SecondEdition, University of ChicagoPress.

Porter, M. 1980. Competitive Strategy, Free Press, New

York.

Price Waterhouse. 1995. "Welcome to Knowledge

View."

Price Waterhouse. 1997. "International

Business

Language," formerly http://www.pw.com/kv/ibltxt.htm

66