From:MAICS-98 Proceedings. Copyright © 1998, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved.

An Exploration of Implicit and Explicit Memory

for Textured Shapes in the Haptic Modality

C. Karlyn Limbird

Earlham College

Earlham College, Box 1177 Richmond, IN 47374, limbich@earlham.edu

previous exposureto stimuli helps one to identify

Abstract

The notion of a dual memorysystem

involving implicit and explicit processing has been

sufficiently examinedfor visual and auditory tasks,

althoughit still lacks foundingin the haptic

modality. Typically, implicit priming is found

only for tasks that require structural encodingsof

a stimulus and explicit memoryis found only for

elaborative tasks, thus demonstratinga

dissociation between the two systems. The

present study explored the effects of these tasks for

the processing of differently textured shapes on

haptic memory. Explicit memorywas clearly

demonstrated; however results show no evidence

of an implicit memorysystem for touch. Several

explanations for these findings are discussed,

including the possible existence of a separate

memorysystem for the haptic modality or the

necessity of a pre-existing representational system.

the samestimuli in later test conditions(Srinivas,

1993).

A large bodyof research exists

documentingthe various dissociations of implicit

and explicit memory.Initial evidence of the two

systems camefrom studies of patients with

neurological disorders such as amnesia.

Amnesiacs often show impaired performance on

explicit memorytasks while exhibiting normal

performance on measures of implicit memory

(e.g., Schacter, Church, & Treadwell, 1994).

several experiments, contingency analysis

indicates that correct recall of a stimulus, an

Recent research has indicated the presence

explicit memory

measure, is not predictive of

of two separate systems within humanmemory.

primingof the sameitem on an implicit test ( e.g.

Explicit memoryappears to contain semantic or

Schacter, Cooper, & Delaney, 1990). This

episodic representations of stimuli that can be

stochastic independenceis evidence for separate

consciouslyrecalled through direct tests of recall

systems. Differences between the two memory

or recognition, hnplicit memoryis tested by

systems have been documentedin verbal and non-

indirect measureseliciting unintentional retrieval

verbal memory(Hamann,1996; Srinivas, 1993),

such as object identification tests. Elaborative

with commonand uncommonobjects (Schacter, et

information helps to encode explicit memories,but

al. 1990; Wippich1991), and in visually,

implicit memoryseems to be more reliant on

auditorily, and haptically presented material

structural mental representations of objects such as

(Musen& Treisman, 1990; Schacter et al., 1994;

shape and form used in identification processes for

Wippich, Mecklenbrauker, & Norbert-Wurm,

efficient encoding(Srinivas, Greene, & Easton,

1994). Witheach dissociation, evidence for the

1997). Implicit priming is demonstrated when

probability of the dual memorysystems grows.

Limbird

33

The majority of our knowledgeof implicit

Schachter, Cooper, and Delaney (1990),

and explicit memoryhas comefrom the

however, describe the change in performance on

dissociative effects of different study tasks

implicit tests as being aided by a perceptual

precedingimplicit and explicit tests. It has often

representation system that encodes a mental

been shownthat perceptual study tasks such as

representation of global componentsof the

wordreading (e.g., Blaxton, 1989; Easton,

stimulus. It has been demonstratedthat this

Srinivas, & Greene,1997), object rating (e.g.,

structural representational system, responsible for

Srinivas, 1993), or physical description creation

implicit memory,depends primarily on physical

(e.g., Hamann,

1996; Srinivas et al., 1997;

cues and relations (Schacter et al., 1990). The

Wippich,1991, Wippichet al., 1994) that allow

representations have been described as pre-

for a structural encodingof the stimulus best

semanticabstract structural descriptions (Srinivas,

facilitate implicit memory.Studytasks that

1991). In this view, the global structural

involve elaborative encodingsuch as associative

impression of a stimulus is encodedindependently

elaboration (e.g., Schacteret al., 1990,Srinivas et

of its local and meaningfulfeatures. One example

al., 1997)or object labeling (e.g., Wippich,1991)

of this is provided by Roediger and Blaxton (1987)

tend to improveparticipants’ performanceon such

whonoted that variance in surface form of words

explicit tests as recognitionor recall.

(such as the font) affects performanceon implicit

There is still considerable disagreementas

tests but not on explicit tests. Thedissociation of

to the theoretical reasonsfor this dissociation.

structural and meaningfulfeatures has also been

Someresearchers insist that dissociated facilitation

demonstrated in an amnesiac patient whoshowed

is duemoreto a similarity in study and test

normalretention of structural knowledgefor

conditions than to two separate memorysystems

objects, but whocould not access functional or

(Blaxton, 1993; Reisberg, 1997). This notion that

associative properties of them (Riddoch

memoryperformance is most successful when

Humphreys,1987). As predicted by transfer-

study and test reinstate the sameprocessing

appropriate processing, implicit primingis often

mechanismsis commonlycalled transfer-

best facilitated whenstudy allows a global

appropriate processing (Morris, Bransford,

structural encodingof the stimulus, whereas

Franks, 1977; Schachter et al., 1990). A further

explicit memoryfunctions best whenan

exampleof a theory designed to explain implicit

elaborative, functional code is formed(Schachter

priming is offered by Reisberg (1997) who

et al., 1990). Suchevidencehas led researchers

hypothesizes that primingeffects are caused by an

and theorists to believe that repetition priming

improvementin processing fluency that eases

shownon implicit memory

tests is a potent

repeated perceptions of the samestimulus, rather

indicator of mentalstructural representations that

than being caused by a specific memorytype

maybe essential to identification of wordsand

storing structural knowledgefor later use.

objects (Eastonet al., 1997).

34 MAICS-98

Concernhas been expressed that the

translating materials used for visual tests into

memorysystem paradigmis invalid in that

stimuli for tactile tasks (e.g., size discrimination,

measures of implicit memoryare contaminated by

spatial localization, verbal processing, picture

previously existing representations used explicitly

identification, etc.) (Lederman,1982; Lederman

(McKone& Slee, 1997). In the manystudies

al., 1990). Lederman(1982), therefore,

measuring implicit memorywith verbal material

recommends

tasks using textural characteristics as

already existing in the mentallexicon (e.g.,

the most valid for haptic examination (Lederman,

Blaxton, 1989; Easton et al., 1997; Hamann,1996,

1982). These characteristics will be the primary

Schachteret al., 1994),it is likely that pre-existing

discriminating traits of the stimuli manipulatedin

representations of words are drawn upon. Even

the following experiment.

whennon-wordsare used as stimuli, there exist

Several studies have showndistinct visual

familiar representationsof letters and letter

and verbal contamination in measuresof haptic

groupings that might be modified and used as

memory.Ledermanet al. (1990) discovered that

explicit memoryin implicit tests (McKone

& Slee,

haptic recognition of two-dimensionalpictures

1997;Schacteret al. 1990). It is also probablethat

was caused by a visual translation process and that

the use of pictures, common

objects, or numbersin

pictures with high imaginability ratings were also

tests of implicit memorymayinvoke somesort of

those best recognized later by touch. Andcontrary

existing verbal representation (e.g., Lawrence,

to the theory of transfer-appropriate processing,

Cobb, & Beard, 1989; Srinivas, 1993; Wippich,

Easton et al. (1997) found no effects of modality

1991; Wippichet al., 1994). Musenand Treisman

change in implicit or explicit memory

for verbal

(1990) suggest that an effective wayof eliminating

material whentest and study conditions changed

this semantic activation is to measurenovel stimuli

from haptic to visual and vice versa. This finding

with no pre-existing representations. The

strongly suggests that verbal material is encoded

experimentat hand study will follow this model.

identically in different presentation modes.And

AltHoughEastonet al. (1997) believe that

although practical and applicable to the outside

the haptic system maybe particularly proficient in

world, studies assessing memory

for Braille (e.g.

perceiving structures, implicit memory

and the

Hamann,1996) are measuring verbal memory

structural representation system have not yet been

rather than haptic performance. Such research

examinedfor tactual stimuli. Most often, memory

clearly indicates the dangerof crossover of

tasks for the haptic domainhave been designed

visualization and verbal representations into pure

around visual perceptual skills rarely performedby

haptic memorymeasures.

touch, thus causing an inherent disadvantage for

The present experiment attempts to

haptic performance(e.g., Easton, et al., 1997,

examineimplicit and explicit memoriesby

Heller, 1989; Lawrenceet al., 1978; Srinivas 1997;

measuringthem in the haptic modality with texture

Wippichet al., 1991, 1994). Researchers have

as the discriminativecharacteristic for the stimuli.

designed most of these measures simply by

A task was designed to minimizeverbal or visual

Limbird

35

contamination for this purpose. As recommended

22, naive to the purposeof the study, voluntarily

by previous studies for most effective processing,

participated in this experiment. Somestudents

a task of active touch was utilized (Lawrenceet

received coursecredit for their participation;

al., 1978; Wippich,1991; Wippichet al., 1994) to

others received food. They were randomly

facilitate natural and efficient performance.

assigned to experimental test conditions. In

Followingthe Schacter et al. (1990) model

addition, five other participants wereused as

transfer-appropriate processing in implicit and

impartial judges and pilot study volunteers.

explicit memoryfor uncommon

objects, this study

Materials

Seventy 13 cmx10 cm stimulus cards

explored the effects of elaborative and global

study tasks on an object identification task as the

were constructed of foam board. Objects of

implicit measureand a recognition task as a

varying texture and consistency(e.g., fabrics,

measure of explicit memory.

plastics, and metals) werecut in rectangular,

If structures underlying the processing of

irregular, or oblong shapes averaging 8 cm x 8 cm

haptically experiencedmaterial operate in the

in size. These were then mountedon the foam

samemanneras those for visually and auditorily

boardcards horizontally, vertically, or diagonally.

presented material, then it maybe assumedthat

No two textures were repeated. The stimuli were

information for objects is encodedsimilarly across

then classified by a panel of 3 judges as

modalities. However,if they do not, then, like

rectangular, oblong, or irregular in shape. Fifty-

Ledermanet al. (1990), we mayneed to consider

two items were chosen as the final experimental

the sense of touch as possibly utilizing a separate

stimuli following the ratings of the judges and

system of processing and memory. If two memory

performanceof the 3 pilot study participants. The

systems are demonstrated, the present study may

cards were randomlyassigned to one of 4 blocks

be used in conjunctionwith studies in other

of 13 stimuli each, with approximatelythe same

modalities for objects without pre-existing

number of each shape in each block. A 60 cmx

representations (e.g., Schacteret al. 1990)

90 cm black opaque curtain was placed between

further substantiate the dual memorysystem. If

experimenter and participant. Reaction time was

implicit memoryis not demonstrated, however, we

measuredin the implicit test phase with a

maybe called to consider the McKoneand Slee

Lafayette Instruments electric timer (model

(1997) proposition that implicit memory

54030).

dependenton pre-existing structural

Design and Procedure

representations that wouldnot exist for a novel

haptic task.

(encodingstatus: elaborative, physical, or nonMethod

Participants

A total of 54 EarlhamCollege

undergraduates (20 men and 34 women)ages 1836 MAICS-98

The experimental design consisted of a 3

studied) x 2 (memorymeasure: shape

identification or object recognition) x 3 (shape:

rectangular, oblong, or irregular) mixedfactorial.

Encodingstatus and shape were manipulated as

within-subject variables and the memorymeasure

minute distracter task of tangramconstruction

was manipulated as a between-subject variable.

immediatelyfollowing the two study conditions.

Twenty-eightstudents participated in the explicit

Participants in the explicit test condition

test and 26 in the implicit test. Twoexperimenters

were then presented with 52 stimulus cards in the

were needed to conduct the experiment; one

same manner,half of them studied and half non-

measuredreaction times and recorded responses,

studied, randomlyintermixed, and then

and the other presented the stimuli. The

administered a standard recognition test. They

experimenter measuring performance was naive as

were instructed to identify the stimuli as either new

to the nature of the study.

(an item they had not felt earlier in the session)

For each participant, one block of 13

old ( an item that they had touchedearlier in the

stimuli was assigned as the elaborative encoding

session) and were given the same two practice

block, one as the physical encoding block, and two

cards with whichto begin. Participants were

as non-studied blocks. The particular blocks

allowed as muchtime as neededfor this task, but

serving as studied or non-studied items were

the duration of the presentation of each stimulus

rotated for each participant to ensure the equal

was approximately 5 seconds. For each participant,

assignment of each block in each condition over

the percentage of correct responses for each shape

the course of the experiment.

was tabulated separately for each encoding

All participants weretested individually.

In the first phase (physical encoding),participants

condition.

For the implicit test condition, participants

wereinstructed to close their eyes, slide their

were given definitions of rectangular, oblong, and

preferred hand under the curtain, and describe the

irregular in the context of the experiment. They

orientation of the stimulus mountedon the card

were presented with the stimuli in the same

(horizontal, vertical, diagonal). Theywere given

manneras in the explicit test and asked to identify

two practice objects preceding presentation of the

the shape of the randomlyintermixed 26 studied

target stimuli in randomorder. A 5 second

and 26 non-studied items as quickly as possible.

exposure was allowed for the orientation

Correct and incorrect responses, as well as reaction

identification of each of the 13 shapesin the first

time, were tabulated separately for each shape and

block. In the second phase (elaborative encoding),

encoding condition.

participants were instructed to formulate an idea of

the composition of the object. They were again

Results

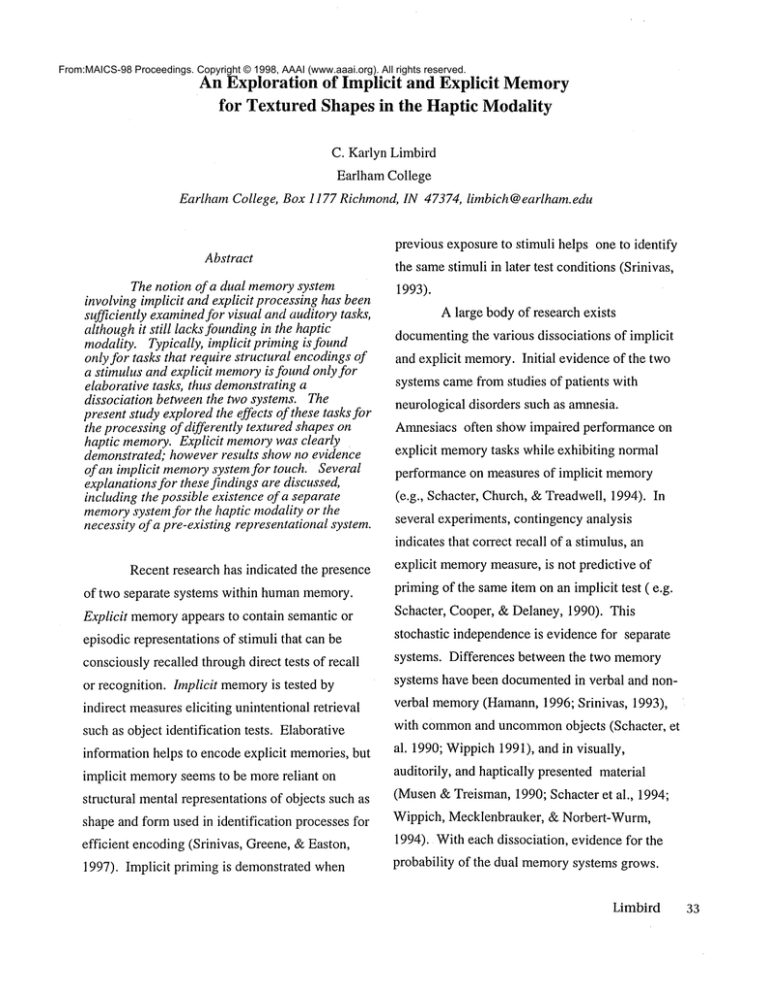

The table belowshows the accuracy rates

allowed5 secondsfor each of the 13 stimuli in that

and RTfor each encoding condition. A repeated

block. In each case, the physical encodingtask

measures analysis of variance found no evidence

preceded the elaborative encodingtask to reduce

either in reaction times (RT), F(2,24) = .23,

the probability of elaborative encodingduring the

.79 or in performanceaccuracy, F(2,24) = .03, p

orientation judgments. Participants were given a 3

.97 for implicit memory.Since no facilitation

(improvementsin accuracy or speed) occurred

Limbird

37

from study conditions in comparisonwith nonstudy conditions, it maybe assumedthat no

MeanPerformance on Explicit (Object

Recognition) and hnplicit (Object Identification)

memorytests as a Function of Study Condition

implicit priming occurred.

Study Status

However,significant evidence for explicit

memorywas obtained. Recognition accuracy for

Test

Elaborative

Physical Nonstudied

the elaborative encoding condition was a 83%

correct recognitionrate, compared

to a little better

than chancerecognition rate for physically

encoded objects (58%chance correct).

Recognition accuracy was calculated as the

percent of correctly identified "old" stimuli for

studied items. Anrepeated measuresanalysis of

variance confirmedthat there wasa statistically

Object

Recognition

.828

.575

.302

Object ID:

Accuracy

.712

RT (in seconds) 4.88

.719

4.94

.722

5.05

Note. Elaborative and physical recognition scores

are the proportions of studied items called as

"old" (hit rate). The non-studiedrecognition score

is the proportion of non-studieditems called "old"

(false alarmrate).

significant interaction betweenthe encoding

conditions and recognition test performance,F (2,

27) = 159.89, p < .0001.

A significant interaction wasfound

memorywas significantly

boosted above chance

levels by elaborative encoding,yet neither

betweenshape and encoding status only on the

structural nor elaborative encodingtasks produced

object recognitiontests, F (2, 27) = 5.81, p

priming or implicit memory.

.0005. Participants demonstratedhigher false

Most important of this study’s

alarm rates for rectangular shapes (41%false) than

implications are those concerningpre-existing

for the others (irregular = 26%false, oblong

structural representations. As explained by

23%false). That is, they were morelikely to

McKoneand Slee (1997), a significant amount

identify a non-studied rectangular shapes as "old"

evidence suggests that implicit memoriesmaybe

than either of the other shapes. Nosignificant

reliant uponpre-existing representations. If this is

influence of hand dominanceor sex was found for

true, then the demonstrationsof implicit memory

either the implicit or explicit measures.These

are not really a uniquesystemat all, but rather the

results suggest that, regardless of object shape,

explicit utilization of previouslystored material.

implicit primingdoes not occur on a haptic

Underthis supposition, items for whichno

identification test, while explicit memory

is clearly

representations exist will not showeffects of

established by elaborative encoding.

priming. Since there was little chanceof a

Discussion

There are manypoints of interest in these

previously existing record of the task performed

by participants in this experiment,it follows that

findings. Unlike most examinationsof this kind,

no primingfor the encodingof newstructural

no evidence of a second memorysystem was

representations occurred.

obtained. As found by manyresearchers, explicit

38 MAICS-98

The idea of visual crossover

the mindin a repeated perception of that stimulus.

contaminating other experiments in haptic memory It is unclear as to whyno priming of any kind

is also substantiated here. Thesetextured shapes

occurredin the identification test.

Myonly hypothesis for this lack of

did not have easily accessible visual

representations. Therefore, visual encoding was

consistencylies in the participants’ reported stress

unlikely. Acase study reported by Grailet, Seron,

levels uponcompletionof the tasks. Several of the

Bruyer, and Coyette et al. (1990) provides

participants later reported a tense uncertainty in

neuropsychologicalevidence indicating that

the tasks they were performing; they were very

withoutvisual recognition abilities, tactual

nervous about being judged for their responses

recognition is impairedfor structural processing.

(although they performedrelatively well). If stress

Following vascular damageto both cerebral

caused the participants to performinconsistently or

hemispheres,their patient lost the ability to access

morepoorly, this maybe a factor that skewedthe

structural knowledgefrom the tactile modality as

data.

well as visual modality, although he demonstrated

Theresults of this study should be

command

of objects’ semantic properties. It has

cautiously applied to the dual memorysystem

been suggested that the haptic and visual systems

theory. The small amountof existing research in

maybe more closely linked than any (see Easton

the haptic modality does not substantiate the

et al., 1990), Wemayneed to ask if the structural

assumptionthat haptic memoryoperates in the

representations assumedto guide implicit memory

samewayas the other systems. In fact, in one

are moreclosely tied to visual abilities than a

case of amnesia, the patient demonstratednormal

memory system.

short-term memoryperformance, while he

These results not only provide no evidence

appeared to demonstrate tactile amnesia(Scarpa

for haptic implicit memory;they also contradict

Sorgato, 1990). Suchevidence indicates the

the widelyaccepted idea of transfer-appropriate

possibility of a separate memorysystem for the

processing. It is puzzlingthat a task of structural

haptic modality.

orientation identification providedno facilitation

Muchmore should be done to bring these

of the later identification of the samestimuli’s

questions to light. AlthoughEaston et al. (1997)

shape. If this study had followedthe patterns of

encouragethe exploration of haptic structural

implicit memory

for novel shapes in the visual

perception and memory, Lederman(1982)

domain(Schacter et al., 1990), we wouldexpect

discourages the use of touch for determining

study task that required structural processingto

structural characteristics such as form, orientation,

somehow

aid the identification of those structures

and localization. If implicit memory

is based on a

in the test phase. Even Reisberg’s (1997) theory

system of structural perceptual representation, and

of processingfluency fails to apply to these

touch is not suited for structural judgments,then

results. Underhis assumptions, any exposure to a

the haptic modalityis not suited for exploring

stimuli under the appropriate conditions will aid

implicit memory.Measureslacking in structural

Limbird

39

components,such as tasks involving two-point

sensation discrimination, temperature, or moisture

might be more reasonable for measuring memory

in this domain.However,if the nature of implicit

memoryis indeed structural, such experimentation

mightnot be fruitful.

Afuture challenge mightbe

to explore other areas of the tactual domainto

clarify the present results andqueries.

References

Blaxton, T.A. (1989). Investigating

dissociations amongmemorymeasures: support

for a transfer-appropriate processing framework.

JotoTzal of ExperimentalPsychology:Lear~ffng,

Memory,and Cognition, 15~ 657-668.

Easton, R.D., Srinivas, K., & Greene, A.J.

(1997). Do vision and haptics share common

representations? Implicit and explicit memory

within and between modalities. Journal of

Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory,

and Cognition, 23, 153-163.

Grailet, J.M., Seron, X., Brayer, R., &

Coyette, F. et al. (1990). Casereport of a visual

integrative agnosia. IOn-line]. Cognitive

Neuropsychology,7, 275-309. Abstract from:

DIALOGFile: PsychlNFO Item: 78-04979

Hamann,S.B. (1996). Implicit memory

the tactile modality: Evidencefrom Braille stem

completionin the blind. PsychologicalScience, 7,

284-288.

Heller, M.A.(1982). Visual and tactual

perception: Intersensory cooperation. Perception

and Psychophysics, 31,339-344.

Heller, M.A. (1989). Tactile memory

sighted and blind observers: the influence of

orientation and rate of presentation. Perception,

18, 121-133.

Hurley, G. & Kamil, M.L. (1976).

Confusionsin memory

for tactile presentations of

letters. Bullethz of the Psychonomic

Society, 8, 7678.

Kazen-Saad, M. (1986). Visual

recognition of equivalent tactile kinesthetic and

verbal information in short-term memory.

Perceptual and MotorSkills, 63, 547-552.

Lawrence,D.M., Cobb, N.J., & Beard, J.I.

(1978). Influence of active encoding

recognition memoryfor commonobjects.

Perceptual and MotorSkills, 47, 596-598.

Lederman.S.J. (1982). The perception

texture by touch. In W. Schiff & E. Foulke (Eds.),

Tactual Perception: a Sourcebook(pp. 130-167).

Cambridge, MA:CambridgeUniversity Press.

40 MAICS-98

Lederman,S.J., Klatzky, R., Chataway,

C., & Summers,C. (1990). Visual mediation and

the haptic recognition of two-dimensionalpictures

of commonobjects. Perception and

Psychophysics, 47, 54-64.

McKone,E. & Slee, J.A. (1997). Explicit

contamination in "implicit memoryfor new

associations. Memoryand Cognition, 25, 352-365.

Morris, C.D., Bransford, J.D., & Franks,

J.J. (1977). Levels of processingversus transfer

appropriate processing. Journal of Verbal

Learning and Verbal Behavior, 16, 519-533.

Musen, G. & Treisman, A. (i990).

Implicit and explicit memory

for visual patterns.

Journal of Experimental Psychology: Language,

Memory,and Cognition, 16, 127-137.

Reisberg, D. (1997). Cognition:

Exploring the Science of the Mind. W.W.Norton

& Co.: NewYork.

Riddoch & Humphreys(1987). Visual

object processing in optic aphasia: Acase of

semantic access agnosia. IOn-line]. Cognitive

Neuropsychology,4, 131 - 185.

Roediger, H. & Blaxton, T.A. (1987).

Effects of varying modality, surface features, and

retention interval on priming in wordfragment

completion. Memoryand Cognition, 15, 379-388.

Scarpa, M. & Sorgato, P. (1990).

Disconnection syndromeand verbal, spatial and

tactile amnesiafollowing a tumor of the spleniem

of the corpus callosum. Behavioral Neurology, 3,

65-75. Abstract form:

Schachter, D. L., Church, B., & Treadwell,

J. (I 994). Implicit memory

in armaesiacpatients:

Evidencefor spared auditory priming.

Psychological Science, 5, 20-25.

Schachter, D. L., Cooper, L.A., &, S.M.

(1990). Implicit memoryfor unfamiliar objects

dependson access to structural descriptions.

Journal of Experimental Psychology: General,

119, 5-24.

Srinivas, K. (1993). Perceptual specificity

in nonverbal priming. Journal of Experimental

Psychology: Learning, Memory,and Cognition,

19, 582-600.

Srinivas, K., Greene, A. J., & Easton, R.

D. (1997). Implicit and explicit memoryfor

haptically experienced two-dimensionalpatterns.

Psychological Science, 8,243-246.

Wippich, W. (1991). Haptic information

processing in direct and indirect memory

tests.

Psychological Research, 53, 162-168.

Wippich, W., Mecklenbrauker, S., &

Norbert-Wurrn, J. (1994). Motorische und

sensorische effekte haptischer erfahrungen bei

impliziten und expliziten ged~ichtnisprfifungen.

Zeitschrift fiir Experimentelle und Angewandte

Psychologie, XL[, 500-522.