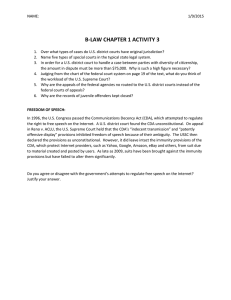

Department of Justice Brief

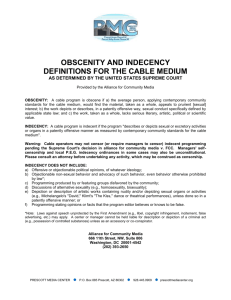

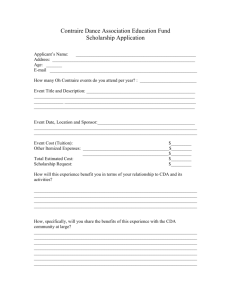

advertisement