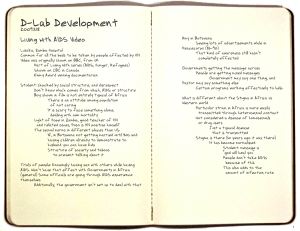

CENTER FOR GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT HIV/AIDS: MONEY, BOTTLENECKS, AND THE FUTURE

advertisement