FACETED ID/ENTITY: Managing representation in a digital world danah boyd

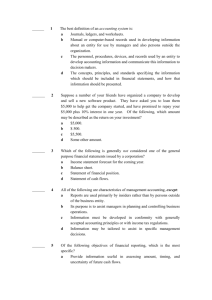

advertisement