INFLUENCE OF LAND-USE CHANGES IN RIVER BASINS ON

advertisement

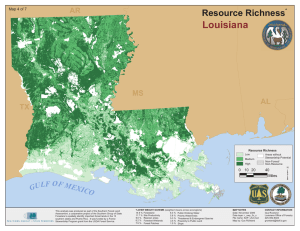

INFLUENCE OF LAND-USE CHANGES IN RIVER BASINS ON DIVERSITY AND DISTRIBUTION OF AMPHIBIANS Gururaja K.V., Sameer Ali, and Ramachandra T.V. Energy & Wetlands Research Group, Centre for Ecological Sciences Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560 012 E mail: gururaj@ces.iisc.ernet.in; sameer@ces.iisc.ernet.in; cestvr@ces.iisc.ernet.in Abstract Land-use changes influence local biodiversity directly, and also cumulatively, contribute to regional and global changes in natural systems and quality of life. Consequent to these, direct impacts on the natural resources that support the health and integrity of living beings are evident in recent times. The Western Ghats being one of the global biodiversity hotspots, is reeling under a tremendous pressure from human induced changes in terms of developmental projects like hydel or thermal power plants, big dams, mining activities, unplanned agricultural practices, monoculture plantations, illegal timber logging, etc. This has led to the once contiguous forest habitats to be fragmented in patches, which in turn has led to the shrinkage of original habitat for the wildlife, change in the hydrological regime of the catchment, decreased inflow in streams, human-animal conflicts, etc. Under such circumstances, a proper management practice is called for requiring suitable biological indicators to show the impact of these changes, set priority regions and in developing models for conservation planning. Amphibians are regarded as one of the best biological indicators due to their sensitivity to even the slightest changes in the environment and hence they could be used as surrogates in conservation and management practices. They are the predominating vertebrates with a high degree of endemism (78%) in Western Ghats. The present study is an attempt to bring in the impacts of various land-uses on anuran distribution in three river basins. Sampling was carried out for amphibians during all seasons of 2003-2006 in basins of Sharavathi, Aghanashini and Bedthi. There are as many as 46 species in the region, one of which is new to science and nearly 59% of them are endemic to the Western Ghats. They belong to nine families, Dicroglossidae being represented by 14 species, followed by Rhacophoridae (9 species) and Ranidae (5 species). Species richness is high in Sharavathi river basin, with 36 species, followed by Bedthi 33 and Aghanashini 27. The impact of land-use changes, was investigated in the upper catchment of Sharavathi river basin. Species diversity indices, relative abundance values, percentage endemics gave clear indication of differences in each sub-catchment. Karl Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was calculated between species richness, endemics, environmental descriptors, land-use classes and fragmentation metrics. Principal component analysis was performed to depict the influence of these variables. Results show that sub-catchments with lesser percentage of forest, low canopy cover, higher amount of agricultural area, low rainfall have low species richness, less endemic species and abundant non-endemic species, whereas endemism, species richness and abundance of endemic species are more in the sub-catchments with high tree density, endemic trees, canopy cover, rainfall and lower amount of agriculture fields. This analysis aided in prioritising regions in the Sharavathi river basin for further conservation measures. Introduction Land-use changes as an aftermath of ad-hoc decisions aimed at meeting the needs of human population is considered to be a paramount factor in the decline of biodiversity all over the world. They not only reduce biodiversity of a region, but over time and space, influence on natural resources, hydrology, nutrition cycle, natural habitat, etc. In an area of rapid land-use changes and in an era of mass extinctions, conservation and management of biodiversity is a Herculean task, especially in the species rich tropical region, where the human dependencies on the natural resources are also more. Similar situation prevails in the Western Ghats of India, one of the tropical biodiversity hotspots rich with fauna and flora. It forms about 6% of India’s landmass, but harbours more than 30% of all vertebrate and plant species of India. It is a mountain belt having a spread of about 1600 km in length, 100 km in width and with altitudes ranging from 300-2700 m above msl along the west coast of India (8°N-21°N). The region has varied forest types from tropical evergreen to deciduous to high altitude sholas. It is also an important watershed for peninsular India with as many as 37 west flowing rivers, three major east flowing rivers and innumerable tributaries. The richness and endemism in flora and fauna of this region is well established with over 4,000 species of flowering plants (38% endemics), 330 butterflies (11% endemics), 289 fishes (41% endemics), 135 amphibians (78% endemics), 157 reptiles (62% endemics), 508 birds (4% endemics) and 137 mammals (12% endemics). This mountain stretch has influenced regional tropical climate, hydrology and vegetation and endemic plant species. To a certain extent bringing in biodiversity rich regions under the protected area network viz., national parks and sanctuaries have helped in conservation, but most often they are ad-hoc decisions and not based on systematic studies. In such situations, it becomes imperative that one needs to look for biological indicator species that surrogate for other species and habitat of the region, which ultimately helps in prioritising the conservation areas of a region. Amphibians, the vertebrates with dual life stages are regarded as one of the best biological indicators due to their sensitivity to slightest changes in the environment and they are used as surrogates in conservation and management practices. The objectives of this paper are to: 1. map the diversity and distribution of amphibian species of the region, 2. understand the relationship of amphibian diversity with landscape variables, 3. prioritise areas of conservation using this relationship. Materials and methods Study area Three river basins, namely Bedthi, Aghanashini and Sharavathi in the Central Western Ghats (between 12°-16°N) were considered for this study as depicted in Figure 1. These rivers are west flowing rivers and form a part of Uttara Kannada, the district with highest forest cover (78%) in Karnataka. % % Kali river Bedthi river Aghanashini river Sharavathi river Venkatapura river Kali river Bedthi river Aghanashini river Sharavathi river Venkatapura river Figure 1. False colour composite image of Uttara Kannada district - study area in the Western Ghats. River Bedthi originates at Dharwad District as Shalmala and confluences at Kalghatgi with another stream from Hubli flowing westward for about 161 km to merge with Arabian sea. It has a catchment of about 3878 sq. km. Similarly, river Sharavathi originates near Ambuthirtha of Shimoga district, traverses for about 132 km and confluences at Honnavar to the Arabian sea. The magnificent waterfall, Jog, is situated in the course of this river. The catchment area of this river is about 3005 sq.km. These two rivers originate in neighbouring districts, but more than 60% of their drainage networks are within Uttara Kannada district. River Aghanashini having a catchment of about 1390.52 sq.km traverses westward for about 121 km from the origin at Manjguni of Uttara Kannada itself and confluences with Arabian Sea at Tadri. Though the catchment of all these river basins have the influence of land-use change, it is more evident in the catchments of River Sharavathi, where four hydel projects have came up since 1930s. Similar situations are expected in Aghanashini as a thermal power plant is expected at Tadri and in Bedthi, with numerous expansions of road networks, transmission lines, etc. To study the influence of land-use changes, upper catchment area of 1991.43 sq. km of Sharavathi River basin is considered (Figure 2) Figure 2. Classified image of Sharavathi upper catchment. Dark circles indicate sampling localities. Sampling methods Amphibian diversity and distribution: Systematic surveys of amphibians are being carried out in the entire district in all seasons, since 2003. Visual encounters, calls, tadpoles, foam nests, spawn are used to record the amphibians in the field. Two man hours of searching is made using torch lights between 19:00-20:00 hr, by walking across the streams, forest floors, gleaning leaf litters, prodding bushes, wood logs, rock crevices, etc. All the species encountered are identified up to species level (if not up to genus level) using the keys of Bossuyt and Dubois (2001) and Daniels (2005). Opportunistic encounters are also recorded to enlist the species of the region. Environmental descriptors: Rainfall data are collected from the nearest rain gauge station for the past twenty years. Mean annual rainfall for this period is considered for the analysis. For canopy coverage, densio-meters are used. Stream flow is graded on the basis of water persistence in the entire year. Vegetation sampling were carried out to calculate percentage tree endemics and evergreenness of the sub-catchments. Land-use and fragmentation metrics: Land-use classification was carried out using remote sensing data through supervised classification technique based on Gaussian Maximum Likelihood algorithm. Satellite imageries from IRS 1C MSS (Indian Remote Sensing Satellite 1C - Multi Spectral Sensor of 23.5m resolution) of November 2000 were used for land-use analyses. The land-use categories considered were evergreen to semi-evergreen forests, moist deciduous forests, plantations, agricultural land and the open land. FRAGSTATS (McGarigal and Marks, 1995), a landscape spatial pattern analysis software is used determine the total edge, edge density, landscape shape index, contiguous forest patch and Shannon’s index. We used forest fragmentation index of Hurd et.al., (2002) to measure the forest fragmentation in the region. Statistical Analysis: Diversity indices were calculated for amphibian species abundance. Correlation coefficients (r) were calculated to measure the relationships between various environmental descriptors with the species data. A multivariate analysis, PCA was performed to see the influence of these environmental descriptors in the sub-catchments of the study area. Results Amphibian diversity and distribution: There were as many as 46 species of amphibians recorded from the entire study region. This is nearly 34% of observed amphibians from the Western Ghats. Among these, one species is new to science and 59% are endemic to the Western Ghats. Table 1 lists species belonging to nine families that were recorded from the study area. Family Dicroglossidae and Rhacophoridae were represented by 14 and 9 respectively, followed by Ranidae (5 species). Species richness is high in Sharavathi river basin, with 36 species, followed by Bedthi 33 and Aghanashini 27. Table 1. Species diversity in the three river basins of Uttara Kannada district. Family: Bufonidae Bufo melanostictus Bufo scaber Bufo sp. Pedostibes tuberculosus Family: Microhylidae Ramanella montana Sub-family: Microhylinae Kaloula pulchra Microhyla ornata Microhyla rubra Family: Micrixalidae Micrixalus fuscus Micrixalus gadgili Micrixalus saxicola Family: Petrapedatidae Indirana beddomii Indirana semipalmatus Family: Dicroglossidae Sub-family: Dicroglossinae Euphlyctis cyanophlyctis Euphlyctis hexadactylus Fejervarya brevipalmatus Fejervarya keralensis Fejervarya limnocharis Fejervarya syhadrensis Fejervarya sp. Hoplobatrachus crassus Hoplobatrachus tigerinus Minervarya syhadris Minervarya sp. Sphaerotheca breviceps Sphaerotheca rufescens Sphearoteca dobsonii Family: Rhacophoridae Sub-family: Rhacophorinae Aghanashini Sharavathi Bedthi + + + + + + + + + + + Endemic LC LC + EN + NT + + + + + + + + + + LC LC LC + + + + + + + + + NT EN VU + + + + + + LC LC + + + + + LC LC DD LC LC LC + + + + + + + + + + + + + GAA + + + + + + + + + + LC LC EN LC LC LC Philautus cf.leucorhinus Philautus cf.luteolus Philautus cf.nasutus Philautus cf.ponmudi Philautus tuberohumerus Polypedates leucomystax + + + + + + + + + + + Sharavathi + + + + + + + + + + + EX VU EX VU VU LC GAA LC LC LC Aghanashini Bedti Endemism Polypedates maculatus + Polypedates pseudocruciger + + Rhacophorus malabaricus + + Family: Nyctibatrachidae Nyctibatrachus cf. aliciae + + + + EN Nyctibatrachus major + + + + VU Nyctibatrachus cf. petraeus + + + EN Family: Ranidae Clinotarsus curtipes + + + NT Hydrophylax malabaricus + + LC Sylvirana aurantiaca + + + VU Sylvirana sp. + Slyvirana temporalis + + + NT Family: Ichthyophiidae Ichthyophis beddomi + + LC Ichthyophis malabaricus + + LC Species richness 27 36 33 24 Note: E-endemic; NE-non-endemic; GAA-Global Amphibian Assessment; EX-Extinct from type locality; ENEndangered; Vu-Vulnerable; NT-Near threatened; LC-Least concerned, DD-Data deficient Number of endemic species varied among the river basins, highest being in Sharavathi with 21 species, followed by Bedthi with 24 and Aghanashini with 14 species. Overall 2 species are extinct from the type locality, 5 species are endangered and 6 are vulnerable. Sharavathi and Aghanashini harbour both extinct species, while Bedthi harbours only one. Four endangered and all six vulnerable species are found in Sharavathi, whereas, in Aghanashini and Bedthi, this amounts to 3, 4 and 4, 5 respectively. Environmental descriptors and amphibian diversity: Table 2 details the correlation coefficient (r) at statistically significant level (P <0.05) for endemic species richness and abundance with environmental descriptors, land-use, fragmentation and landscape metrics. Endemic species richness is positively influenced by tree endemism; tree evergreenness; stream flow; canopy and rainfall. Similar among the land-use categories, evergreen-semi-evergreen has exhibited positive correlation with endemic species richness and abundance. The landscape metrics also have influenced species richness. Among the negatively influencing factors, agriculture, open-lands and moist-deciduous categories reduce both endemic richness as well as abundance. Similarly, patch forest negatively influences the richness and abundance. Table 2. Correlation coefficient (r) at significance level (P<0.05) between endemic species richness and abundance with environmental descriptors, land-use, fragmentation and landscape metrics. Endemic species richness Endemic abundance Environmental descriptors Tree endemism (%) 0.513 Evergreenness (%) 0.544 Stream flow (%) 0.817 0.607 Canopy (%) 0.643 0.580 Rainfall (mm) 0.892 0.700 Land-use (%) Evergreen–semievergreen (%) 0.853 0.617 Moist deciduous (%) -0.737 -0.735 Agriculture (%) -0.734 -0.585 Open land (%) -0.783 -0.659 Forest fragmentation index Interior (%) 0.635 Patch (%) -0.709 -0.577 Landscape pattern metrics Shape index 0.791 Contiguous patch (m2) -0.809 Shannon’s index 0.842 0.618 Total edge (m) 0.832 0.551 Edge density (#/area) 0.715 Relationships among the environmental descriptors Table 3 details the correlation coefficient at statistically significant level between various environmental descriptors. It is clear from the table that the variables that influence endemic species and abundance also influence each other. In order to project the influence of all these variables in reduced space, Principal Component Analysis, a multivariate analysis is run using MVSP3.2. Figure 3 depicts the plot of Principal Axis 1 and 2, with the variables and subcatchments. Principal Axis 1 explains for 86.13% of the variability and Axis 2 for 7.59%. Table 4 gives the Principal Component loading on Axis 1 and 2. Table 3. Correlation coefficient (r) at significance level (P<0.05) among the environmental descriptors. 1. Tree endemism; 2. Evergreenness; 3. Stream flow; 4. Canopy; 5. Rainfall; 6. Evergreen-semievergreen; 7. Moistdeciduous; 8. Agriculture; 9. Open land; 10. Interior; 11. Perforated; 12. Patch; 13. Shape index; 14. Contiguous patch; 15. Shannon’s index; 16. Total edge; 17. Edge density 1 2 3 4 2 0.985 3 0.812 0.855 4 0.675 0.704 0.628 5 0.791 0.824 0.973 0.749 6 0.858 0.878 0.965 0.771 7 -0.600 -0.703 -0.800 -0.811 8 -0.667 -0.701 -0.920 9 -0.697 -0.726 -0.866 10 0.701 0.695 11 0.736 12 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 0.992 -0.825 -0.797 -0.888 -0.860 -0.783 -0.931 -0.922 0.755 0.845 0.806 0.596 0.841 0.847 -0.543 -0.865 -0.942 0.706 0.799 0.526 0.828 0.849 -0.800 -0.885 0.962 -0.674 -0.694 -0.862 -0.644 -0.895 -0.884 0.652 0.891 0.976 -0.979 13 0.873 0.900 0.907 0.762 0.925 0.952 -0.757 -0.697 -0.817 0.711 0.765 14 -0.870 -0.894 -0.906 -0.759 -0.918 -0.941 0.782 0.690 0.761 -0.633 -0.682 0.687 -0.978 15 0.831 0.864 0.923 0.754 0.934 0.944 -0.818 -0.719 -0.773 0.630 0.665 -0.701 0.965 -0.994 16 0.812 0.858 0.896 0.722 0.907 0.921 -0.802 -0.683 -0.752 0.614 0.661 -0.671 0.977 -0.973 0.969 17 0.935 0.943 0.906 0.770 0.917 0.956 -0.714 -0.721 -0.837 0.770 0.814 -0.794 0.978 -0.960 0.941 0.689 -0.928 -0.753 Table 4. Variable loadings of Principal Component Analysis performed for environmental descriptors. Variable loadings PC 1 PC2 Tree endemism (%) 0.233 0.194 Tree evergreenness (%) 0.282 0.231 Stream flow (%) 0.257 -0.087 Canopy (%) 0.086 0.101 Rainfall (mm) 0.191 -0.049 Evergreen-Semi-evergreen (%) 0.509 -0.015 Moist-deciduous (%) -0.101 -0.038 Agriculture (%) -0.373 0.657 Open land (%) -0.133 0.124 Interior forest (%) 0.178 -0.304 Perforated forest (%) 0.101 -0.122 Patch forest (%) -0.143 0.218 Shape index 0.214 0.2 Contiguous forest (m2) -0.157 -0.169 Shannon’s index 0.254 0.232 Total edge (m) 0.364 0.404 0.921 Figure 3. Biplot of Principal Component Analysis performed for environmental descriptors. 1. Nandiholé, 2. Haridravathi, 3. Mavinholé, 4. Sharavathi, 5. Hilkunji, 6. Hurli, 7. Nagodi and 8. Yenneholé. Agriculture field 1.6 Total edge forest 1.0 Open field Axis 2 Evergreenness 4 Patch forest Shannon’s patch index Tree endemism Landscape shape index 0.3 5 2 -1.6 1 -1.0 -0.3 7 0.3 Rain fall 3 -0.3 8 1.0 1.6 Evergreen-Semi-evergreen Stream flow 6 Contiguous forest Interior forest -1.0 -1.6 Vector scaling: 2.50 Axis 1 Figure 4. Conservation priority zones in Sharavathi river basin. 1. Muppane, 2. Vallur and 3. Niluvase. 1 2 3 Based on the amphibian endemic species diversity, environmental descriptors, land-use and fragmentation metrics, three important regions were identified as conservation priority regions and are depicted in Figure 4. Region 1 falls in the protected area of Muppane reserve forest, 2 in Vallur region where as 3 in Niluvase. It is evident from the study that regions with more human induced changes in land-uses, canopy cover, hydrological regimes often provided shelter to generalist amphibian species, whereas the remnant forest patches with higher amount of canopy and vegetation had more endemic species. This again stresses the point that amphibian habitats are being invariably fragmented and destroyed though many more species are yet to be described from this region and whose future are really in danger, calling for intense research in Western Ghats to conserve and understand them better. Acknowledgements We thank Karthick B, Vishnu D Mukri, Sreekantha, Shrikant, Lakshminarayana for their help in the field. The Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India provided the research grant for this study. We thank Karnataka Forest Department for necessary permissions to carryout the research work. References 1. Bossuyt F, Dubois A (2001) A review of the frog genus Philautus Gistel, 1848 (Amphibia, Anura, Ranidae, Rhacophorinae). Zeylanica, 6,1-112. 2. Daniels, R.J.R. (2005). Amphibians of Peninsular India. Universities Press. 3. McGarigal, K., and Marks, B.J. 1995. FRAGSTATS Ver. 2.0. Spatial pattern analysis program for quantifying landscape structure. 4. Hurd, J. D., Wilson, E.H., Civco, D.L. 2002. Development of a forest fragmentation index to quantify the rate of forest change. 2002 ASPRS-ACSM Annual Conference and FIG XXII Congress April 22-26, 2002