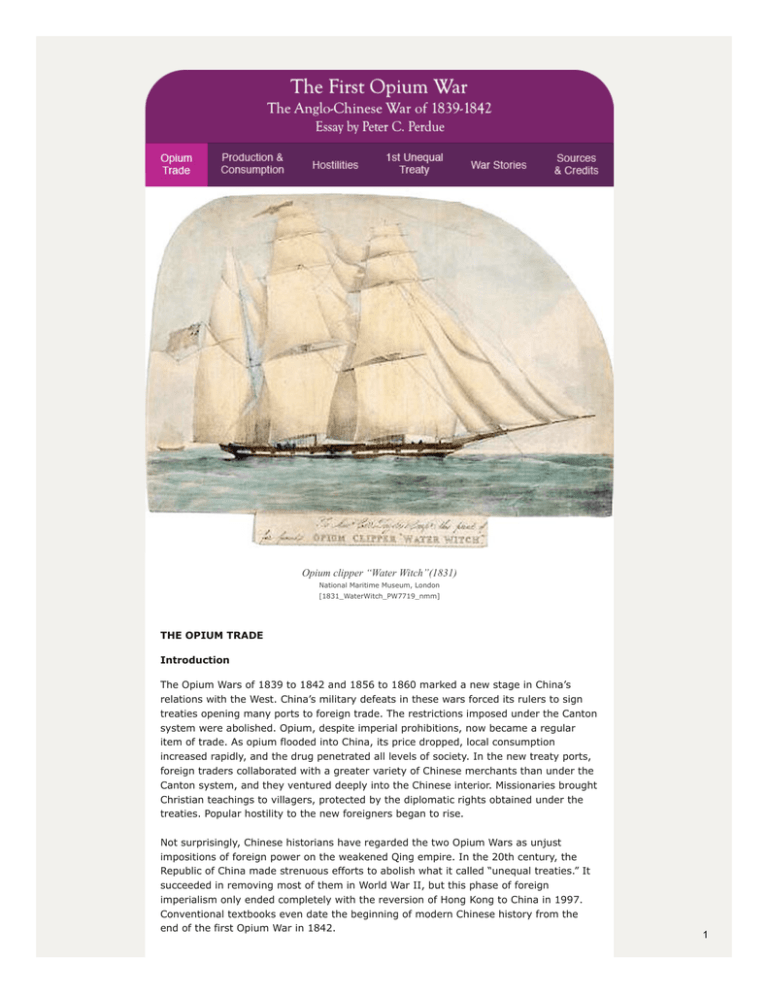

Opium clipper “Water Witch”(1831)

advertisement