Document 13667875

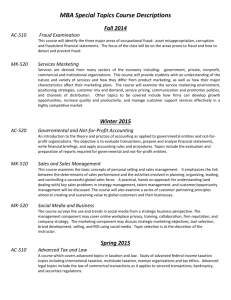

advertisement