From: AAAI Technical Report WS-02-06. Compilation copyright © 2002, AAAI (www.aaai.org). All rights reserved.

Miscomputing Ratio: The Social Cost of Selfish

Computing

Kate Larson and TuomasSandholm

Computer Science Department

Carnegie Mellon University

5000 Forbes Ave

Pittsburgh, PA15213

{klarson,sandholm} @cs.cmu.edu

Abstract

requires computingthe subcontractor’s manufacturing plan.

A normative deliberation control model of how

additional work (e.g., computing) refines valuations was recently introduced (Larson &Sandholm

2001c; 2001b). The authors analyzed auctions

strategically, whereeach agent’s strategy included

both computingand bidding. They found that for

certain auctions, properties such as incentive compatibility cease to holdif agents explicitly deliberate to determinevaluations. Instead agents strategize and counterspeculate, sometimesusing computing to (partially) determine opponents’ valuations. It was conjectured that such strategic computing maylead to inefficient outcomes.

In this paper we introduce a way of measuring the negative impact of agents choosing computing strategies selfishly. Our miscomputingratio isolates the effect of selfish computingfrom

that of selfish bidding. Weshowthat under both

limited computingaffd costly computing,the outcomecan be arbitrarily far worse than in the case

where computations are coordinated. However,under reasonable assumptions on howlimited computing changes valuations, boundscan be obtained.

Finally, we showthat by carefully designing computing cost functions, it is possible to provide appropriate incentives for bidders to choosecomputing policies that result in the optimalsocial welfare.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section describes the auction modeland deliberation

model. The following section discusses whyPareto

efficiency is not necessarily a goodwayof measuring the impact of restricted computingon the outcomeof the auction. This is followed by the introduction of our miscomputingratio, and the results

we derive for it. Weconclude with related work

and a summaryof the paper.

Auctionsare useful mechanism

for allocating items

(goods,tasks, resources,etc.) in multiagentsystems. Thebulk of auction theory assumesthat the

bidders’valuationsfor itemsare givena priori. In

manyapplications, however,the bidders need to

expendsignificant effort to determinetheir valuations. In this paperweanalyzecomputational

bidder agentsthat canrefine their valuations(ownand

others’) using computation.Weintroducea wayof

measuringthe negativeimpactof agents choosing

computingstrategies selfishly. Ourmiscomputin

8

ratio isolates the effect of selfish computing

from

that of selfish bidding. Weshowthat underboth

limited computingand costly computing,the outcomecan be arbitrarily far worsethan in the case

wherecomputationsare coordinated.However,

under reasonable assumptionson howlimited computingchangesvaluations,boundscanbe obtained.

Finally, weshowthat by carefully designingcomputingcost functions,it is possibleto provideappropriateincentivesfor biddersto choosecomputingpoliciesthat result in the optimalsocialwelfare.

Introduction

Auctions are useful mechanismsfor allocating

items (goods, tasks, resources, etc.) in multiagent

systems. The bulk of auction theory assumes that

the bidders’ valuations for items are given a prior/. In manyapplications, however, the bidders

need to expendsignificant effort to determinetheir

valuations. This is the case, for example,whenthe

bidders can gather information (Perisco 2000)

whenthe bidders have the pertinent information in

hand, but evaluating it is complex.Thereare a host

of applicationsof the latter that are closely related

to computerscience and AI questions. For example, whena carrier companybids for a transportation task, evaluating the task requires solving the

carrier’s intractable vehicle routing problem(Sandholm 1993). As another example, when a subcontractor bids for a manufacturingjob, evaluating it

The Model

In this section we specify our model. Wefirst review game-theoretic solution concepts, then auctions, and finally present the modelof deliberation

control.

Copyright~) 2002,American

Associationfor Artificial

Intelligence (wwwmaai,org). All rights reserved.

44

Concepts from Game Theory

A gamehas a set of agents and a set of outcomes

O. Each agent has a set of strategies from which

it choosesa strategy to use. Astrategy is a contingency plan that determines what action the agent

will take at any given point in the game.A strategy profile, s = (sl,..., Sn), is a vector specifying one strategy for each player i in the game.

Weuse the notation 8 = (si, s-i) to denote

strategy profile whereagent/’s strategy is si and

s-i = (sl,..., si-x, Si+l,. ¯ ¯, Sn). Thestrategies

in the profile determinehowthe gameis played out,

and thus determine the outcome o(s) E O. Each

agent i tries to chooseits strategy, si, to as to maximizeits utility, whichis givenby a utility function

ui:O~

Noncooperative game theory is interested in

finding stable points in the space of strategy profiles. Thesestable points are the equilibria of the

game. There are manytypes of equilibria but in

this paper we focus on the two most common

ones:

dominantstrategy equilibria and Nashequilibria.

A strategy is said to be dominantif it is a player’s

strictly best strategy against any strategies that the

other agents mightplay.

) > ~i(O(8~,S--i)).

The strategy is weaklydominantif the inequality is

notstrict.

If each agent’s strategy in a strategy profile is the

agent’s dominantstrategy, then the strategy profile

is a dominantstrategy equilibrium.

Agents maynot always have dominantstrategies

and so dominantstrategy equilibria do not always

exist. Instead a different notion of equilibrium is

often used, that of the Nashequilibrium.

Definition 2 A strategy profile s* is a Nashequilibrium if no agent has incentive to deviate fromhis

strategy given that the other players do not deviate.

Formally,

vi u Co(sL

Another measure that is commonlyused is social welfare. It often allows prioritizing one Pareto

efficient outcomeover another, but it does require

cardinal utility comparisonacross agents.

Definition 4 The social welfare of outcomeo E 0

is SW(o)= Y’~i ui(o)Equilibrium play does not always optimize social welfare. A classic exampleof this is the Prisoner’s Dilemmagame.

The definitions given above were for general

utility functions. However,

in this paper, as is standard whendiscussing auctions, we assumethat the

agents’ utility functions are quasi-linear. That is,

the utility of agent i, ui, is of the formui =vi - Pi

where vi is the amountthat the agent values the

item up for auction and Pi is the amountthat it pays

for the item. If agent i does not win the auction,

then ui = O.

Auctions

In this paper we consider auctions where one good

is being sold. There are numerousauction mechanisms, but in this paper we focus on the Vickrey

auction. In a Vickrey auction (aka. second-price

sealed-bid auction), one good is being sold, each

bidder can submit one sealed bid, the highest bidder wins, but only pays the price of the secondhighest bid. The desirable feature of this mechanism is that if a bidder knowsits private valuation

for the good, the bidder’s (weakly) dominantstrategy is to bid that valuation(rather than strategically

under- or over-bidding). Wechose to study the

Vickreyauction because it has this desirable property in the classic literature, but ceases to havethis

property whenthe bidder agents do not knowtheir

ownvaluations, but rather havethe option of investing computation to determine them. In our model,

the agent’s valuations are independentof each other

as in most of the literature, but wedeviate in that

our agents do not knowtheir ownvaluation a pr/ori.

Definition 1 Agent i’s strategy s~ is a dominant

strategy if

VS-- i V8~ ~ 8~ ~li(O(8*,S--i)

agent has higherutility in o’ than in o, andno agent

has lower utility. Formally,~b’ s.t. ~/i,ui(o’)

ui(o) and 3i ui(o’) > ui(o)].

>

The Nashequilibrium is strict if the inequality is

strict for eachagent.

Normative Model of Deliberation

In this paper, whenever we measure outcomes,

we measurethem from the perspective of the bidders in the auction, not caring about the auctioneer (who is not a strategic agent in our model).

One commonmeasure for comparing outcomes is

Pareto efficiency. It is a desirable measurein the

sense that it does not require cardinal utility comparisons across agents.

Definition 3 An outcomeo is Pareto efficient if

there exists no other outcomeo’ such that some

In order to participate in an auction, agents need

to be able to have a valuation for the items being sold. The question is: Howare these valuations obtained? In this paper we focus on settings

where agents do not simply knowtheir ownvaluations. Rather they have to allocate computational

resources to computethe valuations.

If agents knowtheir ownvaluations (or are able

to determine them with ease) they can execute the

equilibrium bidding strategies for rational agents.

45

movethe agent from parent to child in the tree.

The performanceprofile trees provide information

about howthe solution is likely to improve with

future computation. In particular, if an agent has

reached a solution corresponding to a node in the

tree, then the agent need only consider solutions

in the subtree rooted at the node. The probability of obtaining a solution v’, given that the agent

has reached a node with solution v, is equal to the

product of the probabilities of the edges connecting

nodewith solution v to v’.

There are two different types of performance

profiles: stochastic and deterministic. A stochastic

performanceprofile modelsuncertainty as to what

results future computingwill bring. At least one

node in the tree has multiple children. The uncertainty can come from variation in performance on

different probleminstances or from the use of randomizedalgorithms. A deterministic performance

profile is the special case wherethe algorithm’sperformancecan be projected with certainty (i.e., the

tree is a branch). Witha deterministic performance

profile, an agent can determine what the solution

will be after any numberof computingsteps devoted to the problem---before the agent conducts

any computation. Even though the agent knows

what solution it can obtain, it must still compute

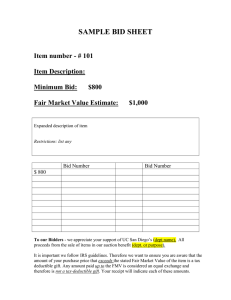

in order to obtain it. Figure 1 is an exampleof a

stochastic performanceprofile tree.

However,agents often haverestrictions on their capabilities for determiningthe valuations. In this paper we are interested in settings whereagents have

to computeto determinevaluations. Settings where

the value of an item dependson howit is used often has this property. For example,valuation determination mayinvolve solving optimization problems that provide a solution as to howthe items in

the auction can be used once obtained. However,

manyoptimization problems, such as scheduling,

are NP-complete.It maynot be feasible to optimally solve the valuation problems. Instead, some

form of approximation must be used. In this paper we assumethat agents have anytime algorithms

(Boddy& Dean1994). The defining property of

anytimealgorithm is that it can be stopped at any

point in time to provide a solution to the problem,

and the quality of the solution improves as more

time is allocated to the problem. This allows a

tradeoff to be madebetween solution quality and

time spent on computing. Since the amountof time

an agent can use to computevaluations is limited

by deadlines or cost, the agents must maketradeoffs in howto determine their valuations. Alone,

anytimealgorithms do not provide a completesolution. Instead, they are paired with a meta-levelcontrol procedure that determines howlong to run an

anytime algorithm, and whento stop and act with

the solution obtained. In this paper we assumethat

agents have a meta-level control procedure in the

form of performance profile trees, based on work

in (Larson &Sandholm200 la).

There is a performanceprofile tree for each valuation problem(one valuation problemper agent).

Figure 1 presents one such tree. The trees are obtained from statistics collected from previous runs

of an algorithm on the valuation problem.The tree

describes howdeliberation (computation) changes

the solution to the valuation problem. Each agent

uses this informationto decide howto allocate its

computingresources at each step in the process,

basedon results of its computingso far.

The trees capture uncertainty that stems from

both randomizedalgorithms and variation of performance on different problem instances. There

are two different types of nodes in the performance

profile tree, solution nodes and randomnodes.

Eachsolution node stores the solution that the algorithm has computedgiven a certain amount of

computation so far. Randomnodes occur whenever

a randomnumberis used to chart the path of the algorithm run. The edges in the tree are labeled with

the probability that after one morestep of computation, the solution returned will be the node found

by following the edge.

Agentsuse the performanceprofile trees to help

in makingdecisions about howto use their computational resources. As agents allocate computational time to an algorithm, the solutions returned

O0

7.O

Figure 1: An agent’s stochastic performanceprofile

tree for a valuation problera~ The diamondshaped

nodes are randomnodes and the round nodes are

solution nodes. At randomnode A, the probability that the randomnumberwill be 0 is P(O), and

the probability that the randomnumberwill be I is

P(1). AT solution node 17,, the edges are labeled

with the probability of reaching each child, given

that node E was reached.

The performanceprofile tree is a fully normative

modelfor deliberation control whichis required for

gametheoretic analysis. It also allows optimal conditioning on manyparameters, including results of

executionso far and on the actual probleminstance.

In the rest of the paper we makethe assumption

that all performance profiles are commonknowledge. This means, that all agents knowwhat all

performanceprofiles look like, and they knowthat

all the agents know.Agentsare allowed to compute

on each others’ problems. Wedo not assume that

agents knowhow their opponents are computing.

46

Strategic

Computing and Bidding

Weconsider two models of computing. In one of

them, computingis free, but there is a deadline for

each agent whenthat agent has to stop computing.

In the other model, the computations do not have

deadlines, but each agent has to pay for the cycles

it consumes. Let T be the time whenthe auction

closes. After that the agent cannot bid or compute valuations. In the modelof limited computing,

each agent has T free computingcycles to use. In

the modelof costly computing,each agent can consumeas manycycles per real-time unit as it wants,

but has to pay a computingcost ca(.).

At every step of the game, each agent can take

a computingaction (the agent can also skip taking a computingaction). Taking a computingaction means allocating one step of computing on

one’s ownvaluation problemor on one of the other

agents’ valuations problems(so as to obtain information about their valuations, which the agent can

use to bid morestrategically to benefit itself). We

say that an agent uses strong strategic computingif

it allocates someof its computingcycles on others’

valuation problems.

At the deadline T, each agent submits one sealed

bid to the Vickreyauction. This bid is the agent’s

bidding strategy. The amount an agent bids dependson the solutions it has obtained for its (and

others’) valuation problemsthrough computing.

It has been shownin earlier workthat the model

of computing(costly or limited) has a significant

impact on what strategies agents mayuse:

Theorem1 Assumethat agents have free but limited computing. Then, in a Vickrey auction, the

bidders have (weakly) dominantstrategies where

they only computeon their own valuation problems

( Larson &Sandholm2001b).

Cost of Selfish

Definition 5 Let o* be the outcomethat is reached

if the global controller dictates computingpolicies

to all agents, andagents are free to bid in the Vickrey auction.

Onthe other extreme, we are interested in what

happens whenagents are free to choose to follow

any computing and bidding strategy. Let NashEq

be the set of Nash equilibria in that game.Wenow

define what is meantby the worst-case Nashequilibrium.

Definition 6 The worst case Nash equilibrium is

NE=

Theorem2 Assumethat agents have unlimited but

costly computing. Then, in a Vickrey auction,

strong strategic computation can occur in strict

Nash equilibrium (Larson & Sandholm2001c).

The Social

right measureto use in the context of computationally boundedagents. Is there an alternative measure?

Instead of looking at efficiency, we propose to

use social welfare as the measure. Wewant to know

howletting agents freely choose their owncomputing strategies impacts the social welfare of the set

of all bidders. In particular, we comparethe highest achievable social welfare to the lowest social

welfare achievable in any Nashequilibrium.

Whenwe determine the highest achievable social welfare we optimistically assumethat there is

a global controller whoimposeseach agent’s computing strategy (so as to maximizesocial welfare).

Thecontroller has full informationabout all performanceprofiles, deadlines, cost functions, and intermediate results of computing,and given this information, specifies exactly howeach agent must use

its computational resources. In the bidding stage

agents are free to bid as they wish, but their goal is

still to maximizetheir ownutility, and so they bid

truthfully in the Vickreyauction, given the valuations they have obtained under the enforced computing policy.

ars~la~hEqill

SW(o(8)).

Weuse the following ratio to see howmuchletting agents choose their owncomputingstrategies

reduces the social welfare.

Definition 7 The miscomputingratio is

Computing

R - SW(o*)

SW(o(NE))

Now,a natural question to ask is whetherthe cost

or limit on computingresources results in a loss

of efficiency. However,efficiency is hard to compare in such settings. The Vickreyauction is efficient in the sense that it alwaysallocates the item to

the bidder with the highest valuation. However,an

agent whomight have been able to obtain the highest valuation via computing,mayhaveused its limited computingon a different problem,thus causing

a different agent to have the highest valuation and

win the auction. This comeis still efficient given

how agents computed, but it overlooks the computational issues in an unsatisfying way. This suggests that Pareto efficiency maynot always be the

This ratio isolates the impact of selfish computing from the traditional strategic bidding behavior

in auctions. This is becausein both the coordinated

and uncoordinated scenario, the agents bid based

on self-interest.

Results

In this next section we present our results in terms

of the miscomputingratio. The first subsection

discusses the general case with limited computing.

The next subsection studies howthe ratio can be

improved when the analyzer has more knowledge.

47

The following subsection studies the general case

with costly computing.The final subsection shows

howthe costs can be adjusted to increase social

welfare.

then the ratio will not be unbounded. Let k be

the difference between the highest possible computed valuation and the second highest possible

computedvaluation. That is

1 max vj (T)]

k = min[max max vi(T) - max

i vi(T)

j~i v~ (T)

General Case with Limited Computing

It turns out that with limited computing,the miscomputingratio can be arbitrarily bad.

Proposition 1 Assume there are n bidders in a

lrtckrey auction, each bidder has free but limited

computing,and the auction closes at time T. Then,

the miscomputing

ratio R can be infinity.

Proof: Assumethat all agents have deterministic

performance profiles. Each agent has a dominant

strategy whichis to deliberate only on its ownvaluation problemuntil the deadline and to submit a

bid equal to the valuation that it has obtained. That

is, agent i submits a bid of vi(T). Withoutloss of

generality, assumethat vt (T) > v2 (T) > vj (T)

for all j ~ 1, 2. In equilibrium, agent 1 will win

the auction and pay an amountof v2 (T). Therefore, agent l’s utility is Ul = Vl (T) - v2 (T).

Ul = e. The utility for all other agents is ui = 0

for i ~ 1. Therefore,

under the constraint that vi(T) > vj(T).

amountk is equal to the lowest possible social welfare obtainable if agents computein a selfish manner. If guarantees on the size of k can be madeby

the restriction of performanceprofile trees then the

miscomputingratio can be madefinite.

Proposition 2 Let

k = min[maxmaxvi(T)

i vi(T)

- max max v~(T)]

j¢i vj(T)

for all i,j and all possible values of vi(T) and

vj(T) under the constraint that vi(T) vj(T).

Thenthe miscomputingratio is

R< maxi max

k vi (T)

General Case with Costly Computing

B

If agents have costly unlimited computing, then

they no longer necessarily have dominantstrategies in the Vickrey auction (see Theorem2). Instead, what they do dependson what strategies the

other agents choose. Whenplacing bids, agents

no longer directly bid the valuation that they have

computed.Instead, they shave the bids downwards.

By constructing appropriate cost functions, it

turns out to be possible to emulate the situation

where agents have free computingbut are limited

by deadlines. Thereforeit is not surprising that under certain circumstances the ratio of the maximum

social welfare to the social welfare obtained from

the worst Nash equilibrium can be unbounded.

SW(o(NE)) = ~ uj

j----1

In order to maximizesocial welfare, the global

controller would prohibit all agents expect for

agent 1 to deliberate. Agent 1 would compute

on its valuation problemuntil time T and submit

a bid of Vl (T) while all other agents wouldsubmit a bid of 0. Agent 1 would win the item and

pay an amountof 0. The utility for agent 1 is

Ux = vl(T) - 0 = Vl(T), while ui = 0 for all

i ¢ 1. Therefore

B

SW(o’)= v, .

Proposition 3 Consider a Vickrey auction with n

bidders. Assumethat each bidder i has costly, unlimited computing. Then, the miscomputing ratio

R can be infinity.

j=l

Theratio, R, is

R= SW(o*) = vl(T)

SW(o(NE))

As e -+ 0 (that is, as the difference betweenthe

highest and second highest valuations decreases),

R-r eo.

[7

This is a negative result. Allowingagents to

choosetheir computingstrategies leads to an outcomethat can be arbitrarily far fromoptimal.

Proof: Assumethat each agent i has the following

cost function,ca (t);

ca(t)

l" 0 ift

oo ift

/

< T;

>T.

Eachagent has a dominantstrategy which is to deliberate only on is ownvaluation problemuntil time

T and then submit a bid of vi(T). That is, each

agent behaves as though they have free but limited computingresources with a deadline at time

T. Like in the proof for the free but limited agents,

Bounding the Miscomputing Ratio Under

Limited Computing

However,in manysituations the miscomputingratio will not be unbounded.Even if the performance

profiles are stochastic, as long as the difference betweenthe highest computedvaluation and the second highest computedvaluation is "large enough",

tlf the performance

profiles are stochasticthere may

be multiple valuations that couldbe computed

for each

agent.

48

compute

assumethat the difference betweenthe highest and

secondhighest bids is e and, without loss of generality, assumethat the highest valuation is vl (T).

Then

compute

no

[]

Adjusting the Computing Cost to Increase

Social Welfare

Prior literature has shownthat in Vickreyauctions,

computationally limited agents have no incentive

to use strong strategic computing(i.e., they do

not counterspeculate each other) while agents with

costly computing do (Larson & Sandholm2001c).

This suggests that if there is a systemdesigner who

can control howthe agents’ computationalcapabilities are restricted, the designer should rather impose limits than costs.

However,it turns out that computingcosts can

be adjusted so that the optimal miscomputingratio

(R = 1) is reached. This wouldmeanthat charging

for computingis at least as desirable as imposing

limits.

0, v2(T)-

vl (T)- c,

0,0

vl (T) -

In this examplethe constant c can be madearbitrarily close to zero. Therefore, the maximum

social welfare generated by the global controller in

the costly computingsetting and be madearbitrarily close to the maximum

social welfare obtainable

if computingresources are free.

[]

Related Research

In auctions, computational limitations have been

discussed both as they pertain to bidding agents

and as they pertain to running the auction (the

mechanism).For bounded-rational bidding agents,

Sandholmnoted that under a modelof costly computing, the dominantstrategy property of Vickrey

auctions fails to hold (Sandholm2000). Instead,

an agent’s best computing action can depend on

the other agents. In recent work, auction settings

where agents have hard valuation problems have

been studied (Larson & Sandholm2001c; 2001b;

Parkes 1999). Parkes presented auction design as

a wayto simplify the meta-deliberation problems

of the agent, with the goal of providing incentives for the "right" agents to deliberate for the

"right" amount of time (Parkes 1999). Recently

Larson and Sandholm have been working on incorporating computingactions into agents’ bidding

strategies using a normativemodelof deliberation

control and have focused on equilibrium analysis of different auction settings underdifferent deliberation limitations (Larson &Sandholm2001b;

2001c). While we borrow the deliberation model

from Larson and Sandholm,this paper addresses a

different question from previous work. They investigate the impact of restricted computingcapabilities on agents’ strategies, we look, instead, at what

the impactis at a system-widelevel, present a measure for comparingoverhead in different settings,

and ask if it is possible to place certain bounds

on the overhead added by having resource-bounded

agents.

Proof: Consider the following example. Let there

be 2 agents, agent 1 and agent 2, each with a deterministic performanceprofile. Assumethat both

agents have free but limited computingresources.

Eachagent has a dominantstrategy, whichis to deliberate on their ownproblemand submit a bid of

vi (T). Assumethat vl (T) > v2 (T). The equilibrium outcomeis to award the item to agent 1 and

have agent 1 pay an amountv2 (T). Agentl’s utility is then ul = vl(T) - v2(T) while agent 2’s

utility is u2 = 0. To maximizesocial welfare the

global controller wouldforbid agent 2 to deliberate,

and thus agent 1 could get the item and need not

pay anything. The maximum

social welfare would

be ul = Vl (T). Therefore

vl(T)

vl (T) - v2(T)

Next, consider the case wherea simple cost function is introduced. Define

ca(t) =

no

-c

R-vx(T)-c-1.

Proposition 4 Computing cost functions can be

used to motivate bidders to choosestrategies that

maximizesocial welfare.

R ----

v2(T),

Table 1: Normal form game. Agent 1 is the row

player and agent 2 is the column player. Each

agent wouldsubmit a bid that is equal to its computed valuation minusthe cost spent to obtain the

valuation.

or not to computeat all. The gamecan be represented in normalform in Table 1.

The sole Nashequilibrium is for agent 1 to compute and submit a bid ofvl (T)-c and for agent 2

not compute. The global controller trying to maximize the social welfare wouldforce each agent to

also follow those strategies. Therefore

R- vl(T)

and as e -~ O, R -~ oo.

’V1 (T)

cift<T;

co if t > T;

for some constant c, 0 < c < v2(T) < vl(T).

Anystrategy that involves deliberating on the other

agent’s valuation problemis dominatedas the computing action incur a cost without improving the

agent’s overall utility. Thus, the remainingstrategies are for the agents to computeonly on their own

valuation problemuntil the cost becomestoo high,

49

There has also been recent workon computationally limited mechanisms.

In particular, research has

focused on the generalized Vickreyauction and has

investigated ways of introducing approximatealgorithms or using heuristics to computeoutcomes

without loosing incentive compatibility (Nisan

Ronen 2000; Kfir-Dahav, Monderer, & Tennenholtz 2000). Our workis different in that it is focused on settings where the agents are computationally limited.

Koutsoupias and Papadimitriou (Koutsoupias

Papadimitriou 1999) first proposed the concept of

worst-case Nash equilibrium. This has been called

the price of anarchy (Papadimitriou 2001). They

focused on a network setting where agents must

decide howmuch traffic to send along paths in

the network. The agents did not have computational limitations. Roughgardenand Tardos studied a different modelof networkrouting using the

same measure as Koutsoupias and Papadimitriou

and obtained tight bounds as to howfar from the

optimal outcomethe agents wouldbe, if allowed to

send traffic as they wished (Roughgarden&Tardos

2000).

Conclusions

Auctionsare useful mechanism

for allocating items

(goods, tasks, resources, etc.) in multiagent systems. The bulk of auction theory assumesthat the

bidders’ valuations for items are given a priori. In

manyapplications, however, the bidders need to

expendsignificant effort to determinetheir valuations. In this paper we studied computationalbidder agents that can refine their valuations (ownand

others’) using computation. Weborroweda normative modelof deliberation control for this purpose.

Wefocused on the Vickrey auction where bidding truthfully is a dominantstrategy in the classical model.It wasrecently shownthat this is not the

case for computationallyrestricted agents. In this

paper we introduced a way of measuring the negative impact of agents choosing computingstrategies selfishly. Our miscomputingratio compares

the social welfare obtainable if a global controller

enforces computingpolicies designed to maximize

social welfare (but does not imposebidding strategies), to the social welfare that is obtained in the

worst Nashequilibrium. This measureisolates the

effect of selfish computingfromthat of selfish bidding.

Weshowed that under both limited computing

and costly computing,the outcomecan be arbitrarily far worse than in the case wherecomputations

are coordinated. However, under reasonable assumptions on howlimited computingchanges valuations, boundscan be obtained. Finally, we showed

that by carefully designing computingcost functions, it is possible to provide appropriate incentives for bidders to choosecomputingpolicies that

result in the optimal social welfare. This suggests

(unlike earlier results) that, if there is a systemdesigner that can choosehowto restrict the agents’

computing, imposing costs instead of limits may

be the fight approach.

Ackowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by

the National Science Foundation under CAREER

Award1RI-9703122, Grant IIS-9800994, and ITR

IIS-0081246.

References

Boddy, M., and Dean, T. 1994. Deliberation scheduling for problem solving in timeconstrained environments.Artificial Intelligence

67:245-285.

Kfir-Dahav, N.; Monderer, D.; and Tennenholtz,

M. 2000. Mechanism design for resource

bounded agents. In Proceedings ICMAS-2000.

Koutsoupias, E., and Papadimitriou, C. 1999.

Worst-case equilibria. In Symposiumon Theoretical Aspects in ComputerScience.

Larson, K., and Sandholm, T. 2001a. Bargaining with limited computation: Deliberation equilibrium. Artificial Intelligence 132(2):183-217.

Larson, K., and Sandholm, T. 200lb. Computationally limited agents in auctions. In AGENTS-01

Workshopof Agents for B2B, 27-34.

Larson, K., and Sandholm,T. 2001c. Costly valuation computationin auctions. In TARKVIII, 169182.

Nisan, N., and Ronen, A. 2000. Computationally

feasible VCGmechanisms.In Proceedings of the

ACMConference on Electronic Commerce,242252.

Papadimitriou, C. 2001. Algorithms, games and

the Internet. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual

ACMSymposium on the Theory of Computing,

749-253.

Parkes, D.C. 1999. Optimal auction design

for agents with hard valuation problems. In

Agent-Mediated Electronic CommerceWorkshop,

IJCAI-99.

Perisco, N. 2000. Informationacquisition in auctions. Econometrica68(1):135-148.

Roughgarden,T., and Tardos, 1~. 2000. Howbad

is selfish routing? In Proceedingsof the 41st Annual IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science.

Sandholm, T. 1993. An implementation of the

contract net protocol based on marginal cost calculations. In AAAI-1993,256-262.

Sandholm,T. 2000. Issues in computationalVickrey auctions. International Journal of Electronic

Commerce4(3): 107-129.

50