DISSERTATION FROM SCOURBUCH TO THE SCURVY: THE ARRIVAL OF A NEW

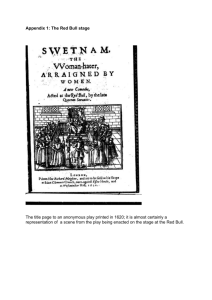

advertisement