-

advertisement

3

AN INTRODUCTION TO VECTOR CALCULUS

A

-

Introduction

I n t h e same way t h a t w e s t u d i e d n u m e r i c a l c a l c u l u s a f t e r we l e a r n e d

n u m e r i c a l a r i t h m e t i c , w e c a n now s t u d y v e c t o r c a l c u l u s s i n c e we have

a l r e a d y s t u d i e d v e c t o r a r i t h m e t i c . Q u i t e simply (and t h i s w i l l be

e x p l o r e d i n t h e remaining s e c t i o n s of t h i s c h a p t e r ) , w e might have a

vector quantity t h a t v a r i e s with respect t o another variable, e i t h e r a

scalar or a vector.

I n t h i s c h a p t e r w e s h a l l b e most i n t e r e s t e d i n

t h e c a s e where w e have a v e c t o r which v a r i e s w i t h r e s p e c t t o a s c a l a r .

A r a t h e r s i m p l e p h y s i c a l s i t u a t i o n of t h i s c a s e would be t h e problem

where w e measure t h e f o r c e on an o b j e c t a t d i f f e r e n t times.

.

That i s ,

f o r c e ( a v e c t o r ) i s t h e n a f u n c t i o n of t i m e ( a s c a l a r )

I n t h i s cont e x t w e can a s k whether o u r f o r c e i s a c o n t i n u o u s f u n c t i o n of t i m e , a

d i f f e r e n t i a b l e f u n c t i o n o f t i m e , and s o f o r t h ,

A t t h e same t i m e ,

t h i s t y p e of e x p l o r a t i o n opens up new avenues of

i n v e s t i g a t i o n and s u p p l i e s u s w i t h e x c e l l e n t p r a c t i c a l r e a s o n s f o r exp l o r i n g t h e r a t h e r a b s t r a c t n o t i o n of h i g h e r dimensional s p a c e s . More

s p e c i f i c a l l y , l e t u s keep i n mind t h a t it i s a r a t h e r overly-simple

s i t u a t i o n i n r e a l l i f e when t h e q u a n t i t y under c o n s i d e r a t i o n depends

on o n l y one o t h e r v a r i a b l e . For example, w i t h r e s p e c t t o our above

i l l u s t r a t i o n of f o r c e depending upon t i m e , l e t u s n o t e t h a t i n a r e a l l i f e s i t u a t i o n t h e o b j e c t w e a r e s t u d y i n g h a s n o n - n e g l i g i b l e s i z e and

f o r t h i s r e a s o n a f o r c e a p p l i e d a t one p o i n t on t h e o b j e c t h a s d i f f e r -

e n t e f f e c t s a t o t h e r - p o i n t s . ~ h u s ,w e might f i n d t h a t o u r v e c t o r

f o r c e depends on t h e f o u r v a r i a b l e s x , y, z , and t . That i s , t h e

f o r c e may be a f u n c t i o n of b o t h p o s i t i o n ( t h r e e dimensions) and t i m e .

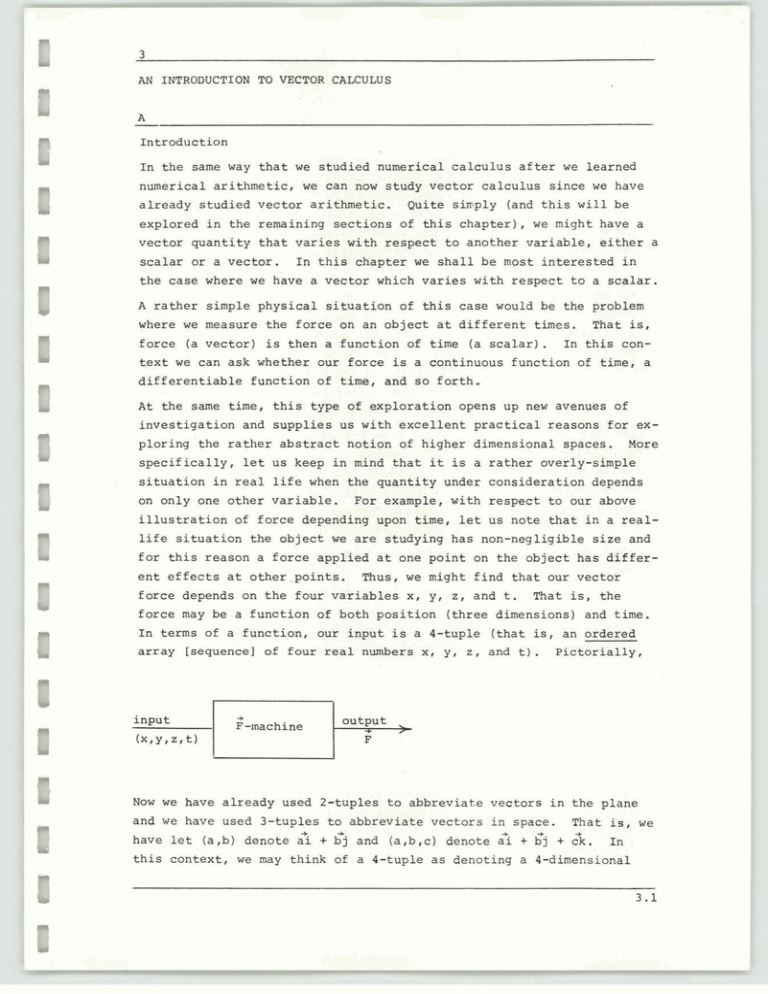

I n terms of a f u n c t i o n , o u r i n p u t i s a 4 - t u p l e ( t h a t i s , an o r d e r e d

a r r a y [sequence] of f o u r r e a l numbers x , y , z , and t ) . P i c t o r i a l l y ,

Now w e have a l r e a d y used 2 - t u p l e s t o a b b r e v i a t e v e c t o r s i n t h e p l a n e

and w e have used 3 - t u p l e s t o a b b r e v i a t e v e c t o r s i n s p a c e . T h a t i s , w e

have l e t ( a , b ) d e n o t e <i + gj and ( a , b , c ) d e n o t e c?i + g j + gk.

In

t h i s c o n t e x t , w e may t h i n k of a 4 - t u p l e a s d e n o t i n g a 4-dimensional

" v e c t o r , " even though we may n o t be a b l e t o v i s u a l i z e it i n t h e u s u a l

sense. We have e a r l i e r come t o g r i p s w i t h t h i s problem i n t h e form of

exponents. Namely, if we look a t b l , b2. and b 3 w e can i n t e r p r e t each

of t h e s e p i c t o r i a l l y v e r y n i c e l y . That i s , b 1 i s a l e n g t h of b u n i t s ,

2

3

b i s t h e a r e a of a square whose s i d e has l e n g t h b , and b i s t h e

volume of a cube whose s i d e has l e n g t h b . But while b 4 does n o t have

such a simple geometric i n t e r p r e t a t i o n , it i s j u s t a s meaningful t o

m u l t i p l y f o u r ( o r more) f a c t o r s of b a s i t i s t o m u l t i p l y one, two,

or three.

In o t h e r words, we a r e back t o a fundamental t o p i c of P a r t 1

of our c o u r s e - a p i c t u r e i s worth a thousand words i f you can draw

it.

-

I n any e v e n t , what w e a r e saying i s t h a t when we s t u d y f u n c t i o n s of n

v a r i a b l e s we a r e i n e f f e c t looking a t an n-dimensional space. I n f a c t

t h i s o f f e r s u s a r a t h e r s t r a i g h t - f o r w a r d , non-mystic i n t e r p r e t a t i o n a s

t o why t i m e i s o f t e n r e f e r r e d t o a s t h e f o u r t h dimension. Namely, i n

most p h y s i c a l s i t u a t i o n s t h e v a r i a b l e we a r e measuring ( a s we d i s c u s s e d

e a r l i e r ) depends on p o s i t i o n and time. P o s i t i o n i n g e n e r a l i n v o l v e s

t h r e e dimensions and time i s then t h e f o u r t h dimension ( v a r i a b l e ) .

Notice t h a t i n t h i s r e s p e c t we can have a s c a l a r (as w e l l a s a v e c t o r )

f u n c t i o n of n-dimensional v e c t o r s (meaning t h e i n p u t c o n s i s t s of n

v a r i a b l e s w h i l e t h e o u t p u t i s a number). For example, we might be

studying temperature ( a s c a l a r ) a s a f u n c t i o n of p o s i t i o n and t i m e , i n

t h e sense t h a t temperature i n g e n e r a l does v a r y from p o i n t t o p o i n t

and a t t h e same p o i n t it u s u a l l y v a r i e s from t i m e t o time.

I n o r d e r n o t t o i n t r o d u c e t o o many new i d e a s a t once, w e s h a l l devote

t h e remainder of t h i s c h a p t e r o n l y t o t h e c a l c u l u s of 2 and 3dimensional v e c t o r s . Once we g a i n some f a m i l i a r i t y with t h i s b a s i c

concept, we s h a l l extend our f r o n t i e r s t o i n c l u d e t h e more g e n e r a l

s t u d y of n-dimensional v e c t o r s , T h i s t o p i c w i l l be d i s c u s s e d i n a

l a t e r c h a p t e r of supplementary n o t e s which w i l l be covered d u r i n g our

s t u d y of Block 3 .

b

Functions R e v i s i t e d

When we f i r s t introduced t h e concept of f u n c t i o n s , we mentioned t h a t a

f u n c t i o n was a r u l e which assigned t o members of one s e t members of

another s e t . W e p o i n t e d o u t t h a t t h e two s e t s involved could be

a r b i t r a r y b u t t h a t i n t h e study of r e a l v a r i a b l e s our a t t e n t i o n , b y

d e f i n i t i o n , i s confined t o t h e case i n which both s e t s a r e s u b s e t s of

t h e r e a l numbers.

W e a l s o developed t h e v i s u a l a i d of t h e f u n c t i o n machine, wherein i f

f :A+B,

w e had

f -machine (elements

(elements The p o i n t of t h i s c h a p t e r i s t h a t , i n t h e r e a l w o r l d , w e a r e o f t e n

c o n f r o n t e d w i t h s i t u a t i o n s i n which w e a r e d e a l i n g w i t h v e c t o r s r a t h e r

t h a n s c a l a r s , whereupon w e have t h e s i t u a t i o n t h a t e i t h e r t h e i n p u t o r

t h e o u t p u t of o u r f-machine could be v e c t o r s .

I n o u r e a r l i e r example, w e spoke of f o r c e ( a v e c t o r ) a s a f u n c t i o n of

t i m e ( a s c a l a r ) . I n t h i s c a s e o u r f-machine l o o k s l i k e

input

t (scalar)

f -machine

+

More c o n c r e t e l y , w e might have a f o r c e F d e f i n e d i n t h e xy-plane by

From (1) it i s c l e a r t h a t d i f f e r e n t v a l u e s of t h e s c a l a r t y i e l d d i f +

f e r e n t v a l u e s of t h e v e c t o r F. F o r i n s t a n c e , i f t = 3 t h e n

8 = 3 1 + $j Moreover, i t s h o u l d seem f a i r l y obvious t h a t w e might

l i k e t o a b b r e v i a t e t h e above i n f o r m a t i o n i n the form

.

Notice how t h e language i n ( 2 ) c l o s e l y p a r a l l e l s t h e n o t a t i o n t h a t w e

have a l r e a d y used f o r " r e g u l a r " f u n c t i o n s . The o n l y d i f f e r e n c e i s

t h a t b e f o r e w e were t a l k i n g a b o u t s c a l a r f u n c t i o n s ( i . e . t h e " o u t p u t s "

were s c a l a r s ) of s c a l a r v a r i a b l e s ( i . e . t h e " i n p u t s " were a l s o

s c a l a r s ) , w h i l e i n t h i s c a s e we a r e d e a l i n g w i t h v e c t o r f u n c t i o n s

( i . e . t h e o u t p u t s a r e v e c t o r s ) of s c a l a r v a r i a b l e s .

I n t h i s same v e i n , we might w r i t e

t o i n d i c a t e t h a t we have a s c a l a r f u n c t i o n ( i . e . t h e o u t p u t of f i s a

s c a l a r ) of a v e c t o r v a r i a b l e ( i . e . t h e i n p u t of t h e £-machine i s a

v e c t o r ) . A s an example i n " r e a l i i f e " ~f e q u a t i o n ( 3 ) , c o n s i d e r a

s i t u a t i o n i n which a l l we were i n t e r e s t e d i n was t h e magnitude of

-+

v a r i o u s f o r c e s being considered. I n t h i s c a s e , given a f o r c e F we

+

would compute i t s magnitude I F ( .

I n t h i s way our procedure i s t o t a k e

a v e c t o r ( f o r c e ) and c o n v e r t i t t o a s c a l a r (magnitude of t h e f o r c e ) .

Pictorially,

input

8 (vector)

1 8 ( -machine

.output

191 ( s c a l a r )

.

The f i n a l p o s s i b i l i t y i s t h a t we have

Equation ( 4 ) denotes a v e c t o r f u n c t i o n of a v e c t o r v a r i a b l e . An

example of t h i s s i t u a t i o n might be t h a t a t any g i v e n i n s t a n t we know

t h e f o r c e ( a v e c t o r ) being e x e r t e d on a p a r t i c l e from which we want t o

determine t h e a c c e l e r a t i o n of t h e p a r t i c l e ( a c c e l e r a t i o n i s a l s o a

v e c t o r - i n f a c t i n Newtonian physics t h e d i r e c t i o n of the a c c e l e r a t i o n

i s t h e same a s t h a t of t h e f o r c e , which means t h a t t h e "lawH f = ma

+

Again p i c t o r i a l l y ,

remains c o r r e c t i n t h e v e c t o r form f = mg)

.

input

3 (vector)

";-machine

"

output

+

a (vector)

/

I n summary t h e n , i f w e allow v e c t o r s a s w e l l a s s c a l a r s t o be our

v a r i a b l e s , t h e n t h e s t u d y of f u n c t i o n s of a s i n g l e v a r i a b l e reduces t o

one of f o u r t y p e s

I n t h i s b l o c k we s h a l l , when d e a l i n g w i t h v e c t o r f u n c t i o n s , assume

t h a t w e have a v e c t o r f u n c t i o n of a s c a l a r v a r i a b l e . T h a t i s , w e

s h a l l d e a l w i t h f u n c t i o n s of t h e form

Pictorially,

x

( s c a l a r1

-t

f -machine

(x,

(vector)

*

The key o b s e r v a t i o n t o b e made from t h e p i c t u r e above i s t h a t i f t h e

a r r o w s a r e o m i t t e d o u r diagram i s i d e n t i c a l w i t h o u r p r e v i o u s diagram

of a f u n c t i o n machine i n t h e s t u d y of r e a l v a r i a b l e s . Namely,

T h i s o b s e r v a t i o n i s t h e backbone of t h e n e x t s e c t i o n .

C

The "Game" Applied t o V e c t o r C a l c u l u s

I n d e f i n i n g l i m f ( x ) = L , w e used o u r i n t u i t i o n t o make s u r e t h a t w e

x+a

knew what w e wanted t h e e x p r e s s i o n t o mean, and we t h e n proceeded t o

make t h e d e f i n i t i o n more r i g o r o u s u s i n g E ' S and 6 ' s .

The r i g o r o u s way

seemed q u i t e f r i g h t e n i n g a t f i r s t , b u t , a f t e r a w h i l e , w e began t o

n o t i c e t h a t it o n l y s a i d i n p r e c i s e m a t h e m a t i c a l terms what we a l r e a d y

believed t o be t r u e i n t u i t i v e l y .

What may have gone u n n o t i c e d was t h a t once we had t h e r i g o r o u s d e f i n i t i o n , e v e r y proof we gave c o n c e r n i n g l i m i t s c o n s i s t e d of a p p l y i n g t h e

r u l e s of mathematics t o t h e mathematical d e f i n i t i o n of a l i m i t .

In

t e r m s of o u r game i d e a , we d e f i n e d what a l i m i t was, used t h e a c c e p t e d

r u l e s of n u m e r i c a l a r i t h m e t i c , and t h e n proved theorems a b o u t l i m i t s .

The key p o i n t h e r e i s t h a t i f it should happen t h a t our d e f i n i t i o n of

l i m i t i n our d i s c u s s i o n of v e c t o r f u n c t i o n s of a s c a l a r v a r i a b l e h a s

t h e same s t r u c t u r e a s our d e f i n i t i o n of l i m i t when w e were d e a l i n g

with s c a l a r f u n c t i o n s of s c a l a r v a r i a b l e s , and i f i t happens t h a t

every accepted r u l e of numerical a r i t h m e t i c t h a t was used i n t h e

e a r l i e r p r o o f s of our l i m i t theorems a l s o happens t o be a n accepted

r u l e f o r v e c t o r a r i t h m e t i c , . th e n , i n terms of t h e philosophy of our

game concept, e v e r y theorem about l i m i t s t h a t was v a l i d i n t h e s t u d y

of "numerical l i m i t s n w i l l remain v a l i d i n t h e study of " v e c t o r i a l

The purpose of t h i s s e c t i o n i s t o e x p l o r e t h i s i d e a i n more

limits."

computational d e t a i l .

How can we t e s t whether t h e v e c t o r s i t u a t i o n p a r a l l e l s t h e numerical

c a s e ? There i s a v e r y e l e g a n t y e t simple technique t h a t we s h a l l

employ h e r e . W e s h a l l begin by w r i t i n g t h e d e f i n i t i o n of l i m i t i n t h e

s c a l a r c a s e . We s h a l l t h e n go through t h e d e f i n i t i o n and i n s e r t arrows

over those symbols t h a t w i l l now denote v e c t o r s r a t h e r t h a n s c a l a r s

(and, a d m i t t e d l y , w e must t a k e c a r e i n determining what i s s t i l l a

s c a l a r and what has become a v e c t o r ) . I n t h i s way, we a r e s u r e t h a t

t h e b a s i c s t r u c t u r e cannot be d i f f e r e n t s i n c e t h e o n l y changes we made

were i n t h e names of t h e v a r i a b l e s . We t h e n check t o s e e i f t h e

r e s u l t i n g d e f i n i t i o n obtained from t h e s c a l a r d e f i n i t i o n by t h i s

"arrowizing" technique i s s t i l l meaningful. For example, i f we t r i e d

t o v e c t o r i z e t h e numerical statement t h a t a/b = c , we would o b t a i n

- + + -b

a / b = c which makes no s e n s e , s i n c e v e c t o r d i v i s i o n i s undefined.

(Of

c o u r s e , had we v e c t o r i z e d a l l b u t b , t h e r e s u l t i n g s t a t e m e n t would

make sense b u t t h i s i s n o t t h e p o i n t w e a r e t r y i n g t o make h e r e . )

I n any e v e n t , c a r r y i n g o u t o u r i n s t r u c t i o n s s o f a r , f i r s t w e w r i t e t h e

o r i g i n a l d e f i n i t i o n of l i m i t i n t h e s c a l a r c a s e , namely

l i m f (x) = L

x+a

means given any E > O , w e can f i n d 6>0 such t h a t whenever

then

Next, we r e w r i t e t h i s d e f i n i t i o n p u t t i n g i n arrows wherever a p p r o p r i a t e . R e c a l l t h a t we a r e d e a l i n g w i t h v e c t o r f u n c t i o n s of s c a l a r

v a r i a b l e s . Hence, x i s a s c a l a r . But f and L should be r e p r e s e n t e d

a s v e c t o r s s i n c e w e have a l r e a d y agreed t h a t we a r e d e a l i n g with vect o r f u n c t i o n s and t h i s i m p l i e s t h a t our o u t p u t , i n t h i s c a s e f ( x ) and

L, a r e a l s o v e c t o r s .

Notice, however, t h a t even though we have now

introduced v e c t o r s , E and 6 are s t i l l s c a l a r s . The reason f o r t h i s

i s t h a t E and 6 denote a b s o l u t e v a l u e s (magnitudes) of q u a n t i t i e s , and

t h e magnitude of both s c a l a r s and v e c t o r s a r e non-negative r e a l

numbers.

I n any e v e n t , i f w e now r e w r i t e our o l d d e f i n i t i o n with t h e

a p p r o p r i a t e "arrowi z a t i o n n w e o b t a i n

means given any E > O we can f i n d 6 > 0 such t h a t whenever

then

Our f i r s t o b s e r v a t i o n of t h i s d e f i n i t i o n should show t h a t i t i s mean+ +

i n g f u l . That i s , e v e r y p a r t of t h e e x p r e s s i o n i s d e f i n e d ( u n l i k e a / b ) .

Ou,r next t a s k i s t o see whether t h e d e f i n i t i o n c a p t u r e s what we would

-+

+

l i k e l i m f ( x ) = L t o mean. A f t e r a l l , what good i s it i f our d e f i n i x+a

t i o n i s meaningful b u t it d o e s n ' t c a p t u r e t h e meaning we have i n mind?

To t h i s end, it i s probably f a i r t o assume t h a t we would l i k e

+

+

-+

l i m f (x) = L t o mean t h a t i f x i s " s u f f i c i e n t l y c l o s e t o " a- then f ( x )

x+a

-+ i s " s u f f i c i e n t l y c l o s e t o " L. Notice t h a t f o r two v e c t o r s t o be " n e a r l y " e q u a l t h e i r d i f f e r e n c e must be small. I n o t h e r words, f o r any p a i r of v e c t o r s A and B , i f we assume t h a t t h e y o r i g i n a t e a t a common p o i n t then t h e i r d i f f e r e n c e i n magnitude i s t h e l e n g t h of t h e v e c t o r t h a t goes from t h e head of one t o t h e head of t h e o t h e r . C l e a r l y , t h e s m a l l e r t h i s v e c t o r i s i n magnitude t h e more " t o g e t h e r " a r e t h e heads of t h e two v e c t o r s . I n terms of our above d e f i n i t i o n , -+

-+

n o t i c e t h a t f ( x ) - L means p i c t o r i a l l y t h a t

The s m a l l e r t h e d i f f e r e n c e between

-+

t h e c l o s e r i s t h e head of f

f ( x ) and

+

t o t h e head of L which means t h a t

i s more n e a r l y e q u a l t o t.

2

(

.

.

I n o t h e r words, t h e n , i n terms of what t h e a n a l y t i c e x p r e s s i o n s mean

g e o m e t r i c a l l y , w e s h o u l d be convinced t h a t t h e f o r m a l d e f i n i t i o n a g r e e s

w i t h o u r i n t u i t i o n . Again, i n t e r m s o f a p i c t u r e

@

If x i s i n h e r e

/

>

x-axis

( C i r c l e of r a d i u s

J

@

of

E

c e n s e r e d a t t h e head of I.) -b

t h e n f ( x ) t e r m i n a t e s i n h e r e ( p r o v i d e d it o r i g i n a t e s a t t h e t a i l

2,.

So f a r , s o good, b u t i f w e want t o be a b l e t o c a p i t a l i z e on o u r game

i d e a , t h e c r u c i a l t e s t now l i e s ahead. R e c a l l t h a t a l l o u r f o r m u l a s

f o r d e r i v a t i v e s stemmed from c e r t a i n b a s i c p r o p e r t i e s of l i m i t s (such

a s t h e l i m i t of a sum i s t h e sum of t h e l i m i t s , and s o o n ) . These

p r o p e r t i e s of l i m i t s followed m a t h e m a t i c a l l y from c e r t a i n p r o p e r t i e s of

r e a l numbers. The k e y now i s t o show t h a t t h e p r o o f s a p p l y v e r b a t i m

when w e r e p l a c e t h e s c a l a r s by a p p r o p r i a t e v e c t o r s .

For example, what w e r e some of t h e p r o p e r t i e s w e used a b o u t a b s o l u t e

v a l u e s i n d e a l i n g w i t h o u r p r o o f s a b o u t l i m i t s ? W e l l , f o r one t h i n g ,

w e used t h e p r o p e r t y t h a t f o r any numbers a and b

The i m p o r t a n t t h i n g i s t h a t i f we now v e c t o r i z e (1) t o o b t a i n

we s e e t h a t ( 2 ) i s a l s o t r u e .

Pictorially,

The l e n g t h of one s i d e of a t r i a n g l e

c a n n o t exceed t h e sum of t h e l e n g t h s

of t h e o t h e r o t h e r two s i d e s .

a

W e a l s o used such f a c t s a s

la1 3 0 and la1 = 0

i f and o n l y i f a = 0 .

obtain

+

la1 3 0 and

121

I f w e now v e c t o r i z e ( 3 ) a p p r o p r i a t e l y , w e

= 0

i f and on'ly i f 2 = 8 . R e c a l l i n g t h a t 1; 1 means t h e magnitude of

i s t r i v i a l t o see t h a t ( 4 ) i s a l s o a t r u e s t a t e m e n t .

g,

it

W e must b e c a r e f u l n o t t o become t o o g l i b i n o u r p r e s e n t approach.

T h a t i s , w e must n o t f e e l t h a t i t i s a t r u i s m t h a t we c a n j u s t v e c t o r i z e e v e r y t h i n g i n s i g h t and o b t a i n t r u e v e c t o r s t a t e m e n t s from t r u e

s c a l a r s t a t e m e n t s . One p l a c e where w e must be v e r y c a r e f u l , f o r

example, i s when w e v e c t o r i z e any n u m e r i c a l s t a t e m e n t t h a t i n v o l v e s

p r o d u c t s . Consider t h e p r o p e r t y of a b s o l u t e v a l u e s t h a t f o r any

numbers a and b

I f we t r y t o v e c t o r i z e ( 5 ) by b r u t e f o r c e we f i n d f o r one t h i n g t h a t

t h e r e s u l t i n g e q u a t i o n may w e l l b e meaningless. F o r i n s t a n c e , t h e

statement

i s meaningless ( i . e . , undefined.) s i n c e w e have n o t y e t d e f i n e d an

That i s , t h e l e f t s i d e of-:

" o r d i n a r y n p r o d u c t of two v e c t o r s -)a$.

Equation ( 6 ) i s u n d e f i n e d . I f we i n t e r p r e t t h e m u l t i p l i c a t i o n a s

s c a l a r m u l t i p l i c a t i o n and v e c t o r i z e Equation ( 5 ) a c c o r d i n g l y , we

obtain

:

(where on t h e r i g h t s i d e we mean t h e u s u a l m u l t i p l i c a t i o n s i n c e both

1 ;Iand I g ]

a r e numbers)

.

The c r u c i a l p o i n t i s t h a t both forms of equation ( 8 ) a r e meaningful b u t they both happen t o be f a l s e . Namely, -

-+ +

a-b =

(;I

IS(

cos

Hence,

since

lcos<l<

1, ( 9 ) y i e l d s the i n t e r e s t i n g , b u t perhaps s h a t t e r i n g

result that

I n a s i m i l a r way,

laxbl =

If1 ( 1

If

b Isin'

. \;

1;1

lgl

(since Isin

I n o t h e r words, any l i m i t proof t h a t involved t h e r e s u l t t h a t t h e

a b s o l u t e v a l u e of a product i s t h e product of t h e a b s o l u t e v a l u e s

might w e l l be f a l s e i n a b s o l u t e v a l u e o r l i m i t problems involving

e i t h e r t h e d o t o r t h e c r o s s product of v e c t o r s .

Rather t h a n b e l a b o r t h i s p o i n t , l e t us i l l u s t r a t e our i d e a s by means

of a few examples; and t o emphasize t h e i r importance, l e t us u t i l i z e

a new s e c t i o n t o d i s c u s s them.

Some L i m i t Theorems f o r Vectors

Theorem 1

Suppose l i r n

x+a

Then l i r n

x+a

a.

f (x)

(f ( x ) +

+

+

+

= Ll and l i r n g ( x ) = L2

x+@

G(x)) =

Zl + t2

.

.

To prove t h i s theorem, w e w r i t e down t h e analogous proof i n t h e s c a l a r

( W e w i l l n o t motivate t h i s proof s i n c e t h i s was a l r e a d y done i n

case.

P a r t 1 of o u r course. However, it w i l l be an i n t e r e s t i n g check f o r

you t o s e e how " n a t u r a l n t h e proof now seems t o you.)

W e had :

Suppose l i r n f (x) = L1 and l i r n f (x) = L2

x+a

x+a

.

Then l i r n [ f ( x ) + g ( x ) l = L1 + L2

x+a

The proof went a s f o l l o w s

(1) Let h ( x ) = f (x)

+

g (x)

.

W e must show t h a t l i m h ( x ) = L1

x+a

(2) Let E > 0 be a r b i t r a r i l y given.

6 2 such t h a t

+

L~

.

Then t h e r e e x i s t numbers 61 and

and

(3)

Let 6 = min {61,62)

.

T h e r e f o r e , 0 < I x - a1 < 6

(4)

But I f ( x )

-

L1l

+

(5) T h e r e f o r e , 0 < Ix

+

Ig(x)

-

a1

If(x)

-

- ~~1

> I[f(x)

< 6 +

L1l

+

I[f(x)

-

Ig(x)

-

L1l

L1l

-

E

L21 <

E

E

+ [(?(XI- 1 2 1 1

+ [g(x)

-

.

(=T+2)

L21I <

E

.

-

a1 < 6

17) Therefore, 0 < Ix

Therefore, l i m h ( x ) = L1 + L2

x+a

.

+

Ih(x)

-

(LL

-

+

L~)I

< t

The key now i s t o observe t h a t e v e r y s t e p i n o u r proof remains v a l i d

when v e c t o r s a r e introduced. Why? W e l l , f o r example, t h e v a l i d i t y of

s t e p (1) r e q u i r e s t h a t t h e sum of two numbers be a number; o t h e r w i s e ,

h ( x ) = f (x) + g ( x ) would be meaningless. To c o n v e r t t h i s i n t o a v e c t o r

s t a t e m e n t we only r e q u i r e t h a t t h e sum of two v e c t o r s be a v e c t o r , and

t h i s w e know is t r u e . The v a l i d i t y of s t e p ( 2 ) depends o n l y on t h e

d e f i n i t i o n of l i m i t and w e have taken c a r e t o m i m i c t h e s c a l a r d e f i n i t i o n i n forming t h e v e c t o r d e f i n i t i o n . S t e p (3) remains v a l i d by

" d e f h u l t H s i n c e only s c a l a r p r o p e r t i e s a r e being used. That i s , both

+

I f ( x ) - LII and I$(x)

LII a r e s c a l a r s .

The v a l i d i t y of s t e p ( 4 )

hinges on t h e " t r i a n g l e i n e q u a l i t y ; " l a + bl 6 la1 + lbl, b u t t h i s , a s

w e have s e e n , i s a l s o v a l i d f o r v e c t o r s . S t e p ( 5 ) is merely s u b s t i t u t i o n of s c a l a r q u a n t i t i e s . A s f o r s t e p ( 6 ) , t h i s f o l l o w s from t h e com-

-

mutative and a s s o c i a t i v e p r o p e r t i e s of numerical a d d i t i o n , and, a s w e

have s e e n , t h e s e p r o p e r t i e s a r e a l s o obeyed i n v e c t o r a d d i t i o n .

~ n ' o t h e rwords, i f we n v e c t o r i z e " t h e s c a l a r p r o o f , t h e r e s u l t i n g proof

i s a v a l i d v e c t o r proof. When w e do t h i s ( j u s t f o r p r a c t i c e ) we o b t a i n :

(1) L e t g ( x ) =

3 (x) +

6 (x).

W e must show t h a t l i m

x+a

h (x)

=

tl + t2 .

,

(2)

Let

E

t h e r e e x i s t numbers 61 and

> 0 be a r b i t r a r i l y given.

6 2 such t h a t

and

.

Let 6 = min {61,62)

Therefore, 0 < I x - a / < 6

(3)

+

+

~ f ( x )- L 1 l

+

I;(x)

+

-121 <

E

(4)

I ~ ( x ) - +~~1

(5) Therefore, 0 < Ix

(7) Therefore, 0

-

I;(x)

+

B U ~

-

a1 < 6

Ix-a1

C

+

Therefore, l i r n B(x) = L1

x+a

i212 I [ % ( X I-

+

+

< 6 +

+

L2

.

i l l + [;(XI

I[%(x)

-

ill

lg(x)

-

( i l + i 2<)El

+ [;(XI

-

i21

I

.

- t 2 1 ~ <E .

I t i s , of c o u r s e , important t o n o t i c e t h a t our v e c t o r proof a s i t

stands i s self-contained.

That i s , it e x i s t s i n i t s own r i g h t even

It's just that

had w e n o t o b t a i n e d it from an e a r l i e r s c a l a r proof.

by observing t h e s i m i l a r i t y i n s t r u c t u r e , we may deduce t h e p r o p e r t i e s

of c e r t a i n v e c t o r f u n c t i o n s from t h e corresponding p r o p e r t i e s of t h e

s c a l a r f u n c t i o n s , and i n t h i s way, we again b e n e f i t from t h e p a r a l l e l

structure.

Theorem 2

+

I f l i m ? ( x ) = L1 and i f l i m g ( x ) =

x+a

x+a

t2, then

i f h(x) =

f (x)

a x )I

Before proceeding w i t h t h e proof of Theorem 2 , we should n o t e t h a t

t h e r e i s more than one way t o form a product of two v e c t o r s . We have

a r b i t r a r i l y e l e c t e d t o t a l k about t h e d o t product. A s i m i l a r proof

holds f o r t h e c r o s s product and w i l l be l e f t a s an e x e r c i s e . I t i s

worth n o t i n g t h a t t h e f a c t t h a t we can form a product of two v e c t o r s

i n more than one way w i l l cause c e r t a i n complications i n v e c t o r calcul u s t h a t d i d n o t e x i s t i n s c a l a r c a l c u l u s , s i n c e t h e r e , a product of

two numbers could be i n t e r p r e t e d i n only one way.

Proof

Had t h i s been w r i t t e n i n terms of s c a l a r s r a t h e r than v e c t o r s , o u r

proof would have taken t h e form

f (x) = [f (x)

-

L1]

+

L1

therefore, If (x) g(x)

-

L1 L21 = IL2[f (x)

+ [f(x)

-

-

+

L1l

Ll[g(x)

Lll [g(x)

-

L2]

- L~II

-

-

Since 1 Ll 1 and1 L2 1 are bounded and both 1 f (x)

Ll 1 and1 g (x)

L2 1 can

be made arbitrarily small by choosing x sufficiently near 5, the right

a. This guarantees that

side of (1) gets arbitrarily small as x

+

- L1 L2) = 0

lim (f(x) g(x)

x+a

lim f (x) g(x) = L1 L2

x+ a

.

If we now repeat this argument with the appropriate "vectorization,"

we have

Therefore, ftx)

3 (XI

=

113(XI - tl1

iCElot.ice t h a t w h i l e , ' f o r -exampl'e,

+

ILl[g(x)'

- t21

1

'11

-

L2]

I

.

I'

+

F. 1 1 g ( x )

221

-

L2

I

our

s t r i n g of i n e q u a l i t i e s r e q u i r e s only t h e weaker r e s u l t t h a t

T h i s , a s we s h a l l s o o n s e e , i s

ILl [ g ( x )

L2]

6

lg(x)

L2

+

v e r y i m p o r t a n t b e c a u s e o f t h e v e c t o r p r o p e r t i e s t h a t la

bl d

-

and

;1

x

I

i~~1

-

I.

1:1 I ~ I

61 < 121 161.

**We p u t t h i s s t e p i n t o e m p h a s i z e t h e f a c t t h a t t h e r u l e s o f o r d i a a r y

algebra carry over very nicely here t o dot products.

therefore,

If (x)

-+

g(x)

-

-+

Ll

-+

L21

- it2

[f (x) -

tl] + El

[;(XI

-

221

(This last step is independent of any vector arithmetic since all dot

products are numbers not vectors.)

61 ,< 121 161 (observe that we don't need

Now since 1;

our last inequality yields

(Notice that there are no dot products here since

are numbers.)

1;

9 ) = 121 1611,

1 t21 , I 'E(x) - El1

etc.

Our last equation has the same properties as (1) and so the desired

result follows.

Additional examples are left for the exercises. Our aim in this section

was simply to illustrate that our limit theorems for scalars do indeed

carry over, and in a rather natural way, to vectors.

E

Derivatives of Vector Functions of Scalar Variables

In the study of ordinary calculus, we mentioned that the study of

differentiation could be viewed as an application of the limit theorems.

That is, when we defined f' by

f' (xl) = lim

Ax+O

f(xl + Ax)

A-x

-

1

f (xl)

every property of f' was then computed by the use of the limit theorems

applied to (1)

.

The point is that we now do the same thing for vectors.

that the expression

T(xl + Ax)

-

T(xl)

We observe

is well-defined since it involves the quotient of a vector and a scalar

and this may ve viewed as scalar multiplication. That is,

scalar

vector

Without belaboring this point, this expression can indeed be thought

of as representing an average rate of change, and, if we then proceed

to the limit, we may think of this as an instantaneous rate of change.

With this as motivation, all we are saying is that it is meaningful to

define f ' by

f v (xl) =

$(x1 + Ax)

lim

AX +O

- f (xl)

1

AX

The key point now is that since the usual recipes for derivatives

follow from the basic properties of limits and since the same limit

theorems are true for vectors as for scalars, it follows that there

will be recipes for vector derivatives similar to those for scalar

derivatives.

For example, it is provable that the derivative of a sum is the sum

of the derivatives. The proof is again verbatim from the proof in the

scalar case.

Without bothering to copy the scalar proof, we write down the vector

proof with the hope that you can recognize that it is the scalar proof

with appropriate vectorization. We have

Let S(x) =

?(XI +

.

;(XI

[h(xl + Ax) - s(xl) ]

-b

Then

if'

(xl) =

lim

Ax+O

=

lim

Ax+O

bx..

+

.

(xl + AX)

Ax) +

+ Ax)

- f (xl)

[f (xl) +

- 1

AX

Ax+O

lim

Ax+O

-

(xl)I

AX

*(xl

=

.

[f

(xl + AX)

AX

-

x

]

g(xl + AX)

AX

+

lim

Ax+O

[$

1

- g(xl)

-t

(xl + Ax)

AX

-~(Ic~)

(since the limit of a sum is the sum of the limits,

as shown in the previous section).

3.16

I n a s i m i l a r way (and t h e d e t a i l s a r e l e f t a s e x e r c i s e s ) , t h e same

product r u l e a p p l i e s t o v e c t o r s . The only d i f f e r e n c e i s t h a t we now

have s e v e r a l t y p e s of products. For example, w e may have t h e product

of a s c a l a r f u n c t i o n w i t h a v e c t o r f u n c t i o n , o r we may have t h e d o t

product of two v e c t o r f u n c t i o n s , o r w e may have t h e c r o s s product of

two v e c t o r f u n c t i o n s .

I n any c a s e , we o b t a i n t h e r e s u l t s

( I n t h i s l a s t c a s e beware of changing t h e r o l e s of t h e f a c t o r s

+

+

a x b = - 6 x ;).I

We even have a form of t h e q u o t i e n t r u l e pravided t h a t our q u o t i e n t

i s a v e c t o r f u n c t i o n d i v i d e d by a s c a l a r . f u n c t i o n ( f o r , otherwise, t h e

q u o t i e n t i s n o t d e f i n e d ) . The formula i s

These formulas have a n i c e a p p l i c a t i o n t o C a r t e s i a n c o o r d i n a t e s . Suppose

F i s a v e c t o r f u n c t i o n of t h e s i n g l e r e a l v a r i a b l e t. For example, we

-k

may be c o n s i d e r i n g f o r c e a s a f u n c t i o n of time. Suppose F has t h e form

-b

and we d e s i r e t o compute d$/dt.

Since t h e d e r i v a t i v e of a sum i s t h e sum of t h e d e r i v a t i v e s , we have

2~:

:

y,L'

,,i

,..-

:..

=

I L*

3.y-

5,

-1.

'.L,

\

.

.

s ri-

*-

g .

US".

*..

.

;r '

Then s i n c e a c o n s t a n t times a v a r i a b l e has a s i t s d e r i v a t i v e t h e c o n s t a n t

t

+

times t h e d e r i v a t i v e of t h e v a r i a b l e , and s i n c e 1, J , and k a r e c o n s t a n t s ,

we o b t a i n :

While this was a specific example, it should be fairly easy to see that, in general, the derivat-ive is obtained by differentiating the components. Further details are left to the text and the exercises, but we want to emphasize again the fact that our definition of limit for vectors, being so closely modeled after the scalar situation, guarantees that the differentiation formulas with which we are already familiar in the scalar case are also valid in the vector case. MIT OpenCourseWare

http://ocw.mit.edu

Resource: Calculus Revisited: Multivariable Calculus

Prof. Herbert Gross

The following may not correspond to a particular course on MIT OpenCourseWare, but has been

provided by the author as an individual learning resource.

For information about citing these materials or our Terms of Use, visit: http://ocw.mit.edu/terms.