F-35 Alternate Engine Program: Background and Issues for Congress Jeremiah Gertler

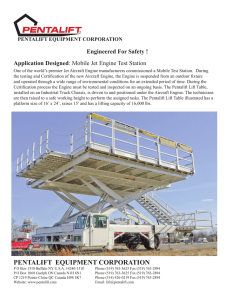

advertisement