The Racial Politics of Urban Celebrations: A Comparative Study of...

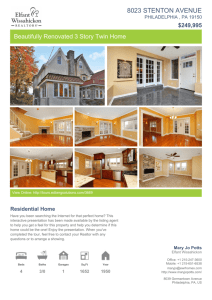

advertisement