THE POLITICS OF EDUCATION AND CRITICAL PEDAGOGY: CONSIDERATIONS IN ‘POST-COLONIAL’ ACADEMIC CONTEXTS

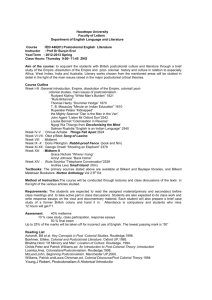

advertisement