Document 13623922

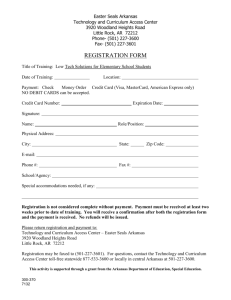

advertisement