Community Design for Healthy Eating How land use and transportation solutions can help

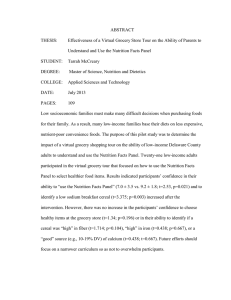

advertisement