Corinth: conflict and community Melbourne/Bendigo Ecclesial Family Camp

advertisement

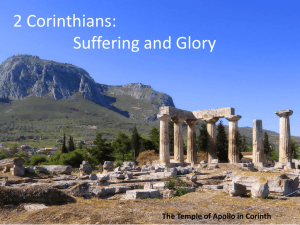

Corinth: conflict and community Melbourne/Bendigo Ecclesial Family Camp 3–5 October 2003 1 Background information 1.1 Chronology of Paul in Corinth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.2 Paul’s letters to Corinth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1.3 The city of Corinth . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 Be of one mind 2.1 Paul’s preaching strategy . . . 2.2 Ecclesial members . . . . . . . 2.3 The Corinth ecclesia . . . . . . 2.4 Divisions in Corinth . . . . . . 2.5 Division and the Lord’s Supper 2.6 Questions . . . . . . . . . . . 3 3 3 4 . . . . . . 8 8 9 11 11 12 13 . . . . . . 14 14 15 16 17 19 20 4 Super apostles! 4.1 False apostles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.2 Paul’s credentials and suffering . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.3 The man with a vision . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21 21 21 22 5 My 5.1 5.2 5.3 23 23 23 24 3 You 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . are still worldly Problems facing the Corinth ecclesia Meat offered to idols . . . . . . . . The problem of tongue speaking . . Chaotic meetings . . . . . . . . . . Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . power is made Paul’s fears . Paul’s thorn in God’s power is 6 Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . perfect in weakness . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . the flesh . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . made perfect when we are weak . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25 Notes by Rob J Hyndman Corinth: conflict and community 2 Corinth: conflict and community 3 1. Background information 1.1 Chronology of Paul in Corinth AD49 Aquila & Priscilla expelled from Rome, go to Corinth. AD50 Paul’s first visit (Acts 18:1–18). Ecclesia begins. AD51 Paul writes 1&2 Thessalonians from Corinth. AD52 Paul, Aquila and Priscilla leave Corinth and go to Ephesus. AD52–53 Paul goes home to Antioch then leaves again on 3rd journey (Acts 18:23). AD53 Paul’s first letter to Corinth? (1 Cor 5:9). AD54 1 Corinthians written while Paul in Ephesus (1 Cor 16:5–9). AD55 Paul’s “painful visit” to Corinth (1 Cor 4:19; 16:5–8; 2 Cor 2:1). AD56 2 Corinthians written while Paul in Macedonia (2 Cor 7:5–9). AD57 Paul’s third visit (2 Cor 12:14; 13:1; Acts 20:2–3). Wrote letter to Romans while there. 1.2 Paul’s letters to Corinth First letter (1 Cor 5:9) Second letter (1 Corinthians) • A response to: • News from Chloe (1 Cor 1:11) • News from Stephanas, Fortunatus and Achaicus (1 Cor 16:17) • Letter from Corinth church (1 Cor 7:1) • Written in tears (2 Cor 2:4) • Sent by Timothy (1 Cor 4:17) Third letter (2 Corinthians) • A response to opponents who questioned Paul’s authority. 1 Corinthians can be divided into two sections: the problems he has heard about and wants to address, and the questions they have raised in their letter to him. • The problems he has heard about are: division, law suits, sexual immorality. • The questions he is replying to: marriage, food sacrificed to idols, spirit gifts, collection. See 1 Cor 7:1,25; 8:1; 12:1; 16:1. 2 Corinthians is largely a defence of Paul’s authority against the false apostles who were gaining a following in Corinth. Corinth: conflict and community 4 1.3 The city of Corinth • City of about 80,000 people. On Peloponnesian peninsula in Achaia. Capital of Achaia. Corinth just south of isthmus. • Busy commercial centre. Junction between east and wet. Hub city for travellers. No roads across central or southern Greece, so all land-travellers went via Corinth. • Economy driven by visitors: religious pilgrims, sailors, merchants, soldiers, slave traders, people in town for the athletic games. • Gateway to west, springboard for Paul’s new journeys to Rome and beyond. Great place to plant the seeds of the gospel because visitors would take it from Corinth back to their home towns. • Controlled major east-west trade. Two sea-ports: Cenchrae to east and Lechaion to west. Ships from east would dock at Cenchrae (10 km east of Corinth), unload their cargo and transport it across to Lechaion on the other side of the isthmus (3km north of Corinth). Smaller ships were actually hauled across the isthmus, without unloading, on a stone paved crossover (6km). This was simpler, safer and quicker than sailing around the peninsula. Greeks had a saying: “Let him who sails round Malea first make his will.” • Near a large mountain known as “Acrocorinth” on which was the temple of Aphrodite. • Also site of temple of Apollo. Corinth: conflict and community 5 Corinth: conflict and community 6 Character of city • renowned for immorality. korinthiazesthai = practise immorality. Or literally, to live a Corinthian life. (Compare Bohemian today) • korinthia kore = prostitute (literally a Corinthian girl). • Strabo says 1000 cult prostitutes served temple to Aphrodite. In the evening, they came down to the streets of Corinth and made money on the streets of the city. • archaeologists have found 33 wineshops on the south side of Roman forum. 2 Cor 12:21; 1 Cor 6:9–11. The Greek writer Aelian says that if ever a Corinthian was a role in a Greek play he was show drunk! • Corinth became a synonym for wealth and luxury, drunkenness and debauchery. Corinth: conflict and community 7 Isthmian games Corinth was the location of the Isthmian games. One of four “major” games held in the empire, the others being the Olympics, Pythian and Nemean games. Held every 2 years including AD49, AD51, AD53, AD55. So they were probably held at least once while Paul was in the city. They would have been very familiar to all ecclesial members. The organizer of the games was the city’s highest ranking official. Games referred to in 1 Cor 9:24–27. • The Greek word for race uses the specific word for a race over a furlong which was about 200m. • “corruptible crown” was wreath made of twigs of fir which grew near the stadium. • quite likely the ecclesia attended the games, and may have even been local officials. They would certainly have been familiar with them as the main sporting event in the empire. • most people stayed in tents. So plenty of work for Paul, Aquila and Priscilla. • Women participated in the games. Corinth: conflict and community 8 2. Be of one mind Reading: 1 Corinthians 11:17–34 2.1 Paul’s preaching strategy • Speak at synagogues first (Acts 18:4). Paul had been a Pharisee. Taught by Gamaliel himself and a learned rabbi in his own right. For such a man to visit Greece would have been a big thing for the Jewish synagogue and he would have been invited to speak to the people. He would certainly have been far more learned than the synagogue ruler. He had not renounced Judaism, so much as adopted a more pure form. See 1 Cor 9:20. • Conversion of synagogue rulers! • Crispus (Acts 18:8) • Sosthenes (Acts 18:12; 1 Cor 1:1) • Tent-making (Acts 18:3; 1 Cor 4:12; 9:6,18). Paul supported himself through tent-making. Meant he could come in contact with many people—visitors to games who stayed in tents, locals needing some leatherwork done (tents were made of leather), etc. Rather than take time away from his preaching, I think this would have assisted his work. People would come to know him, and he could easily talk as he worked. He felt compelled to preach, to reach out to the people he met. And he was willing to be accommodating to their needs and circumstances in order to win them to the gospel. 1 Cor 9:19–22: “I am not anyone’s slave. But I have become a slave to everyone, so that I can win as many people as possible. When I am with the Jews, I live like a Jew to win Jews. They are ruled by the Law of Moses, and I am not. But I live by the Law to win them. And when I am with people who are not ruled by the Law, I forget about the Law to win them. Of course, I never really forget about the law of God. In fact, I am ruled by the law of Christ. When I am with people whose faith is weak, I live as they do to win them. I do everything I can to win everyone I possibly can.” (Contemporary English Version) Would we did the same! Corinth: conflict and community 9 2.2 Ecclesial members The ecclesia grew rapidly. Acts 18:11 List of members 1 Priscilla & Aquila (Acts 18:1–2; 1 Cor 16:8,19; Rom 16:3–5) When Paul left Corinth, they moved to Ephesus (to work with ecclesia there?). Paul later joined them there for three years while on his third journey. While in Ephesus, Paul wrote 1 Corinthians. 1 Cor 16:8,19. So Aquila and Priscilla and the ecclesia in their home. Later (Romans) we find them in Rome. Rom 16:3–5. Church meets at their house again! Paul was writing the book of Romans while he was in Corinth on his second visit to the city near the end of his 3rd journey. 2 Titius Justus (Acts 18:7) 3 Crispus (Acts 18:8; 1 Cor 1:14) 4 Sosthenes (Acts 18:17; 1 Cor 1:1) Synagogue ruler. Helped Paul write 1 Corinthians. Must have been visiting Paul in Ephesus also. 5 Apollos. (Acts 18:24–19:1; 1 Cor 1:12; 1 Cor 3:4) Obviously a powerful orator who used his skills to good effect. Later he attracted a following. 1 Cor 1:12. But Paul saw him as someone who followed up on his initial work. 1 Cor 3:4. 6 Chloe (1 Cor 1:11) Likely to be a wealthy businesswoman who had business interests in both Corinth and Ephesus. 7 Stephanas and household (1 Cor 1:16; 16:15–17) First converts in Achaia. Visited Paul when he was in Ephesus. 8 Fortunatus and Achaicus. (1 Cor 16:17) Visited Paul when he was in Ephesus. 9 Phoebe (Rom 16:1–2) Rom 16:1. Church at Cenchrea only a few km from Corinth. Probably a house church there too which met up with main Corinthian group only occasionally. servant is Greek diakonos. same as deacon. Does not necessarily mean an official position. Can just mean a servant or helper. Also used, e.g., in Mt 20:26; Gal 2:17 (Christ a diakonos of sin). So we shouldn’t read too much into Phoebe being a deaconess here. She probably wasn’t. Rom 16:2 implies she carried this letter from Corinth to Rome. 10 Lucius, Jason, Sosipater (Rom 16:21) Paul’s relatives. Possibly meaning fellow countrymen? Corinth: conflict and community 10 11 Tertius (Rom 16:22) 12 Gaius (Rom 16:23). Church met in his house. Rom 16:23. Possibly they moved after Priscilla & Aquila left Corinth. More likely, there were too many members for one house by this stage anyway, and so they met in more than one home. 13 Erastus (Rom 16:23; 2 Tim 4:20; Acts 19:22) Limestone block found in 1929: “Erastus, in return for aedileship, laid this pavement at his own expense.” More recently, another inscription: “The Vitelli, Frontinus, and Erastus dedicate this to . . . ”. The office he held was called the city “aedile”. This person was responsible for the maintenance of public streets, buildings and marketplaces, and to collect revenues from businesses in such places. He could also be a judge. In order to obtain such a position, you needed to be wealthy. See also 2 Tim 4:20; Acts 19:22. 14 Quartus (Rom 16:23) Corinth: conflict and community 11 2.3 The Corinth ecclesia Allowing for families for these people, my guess is that the Corinthian ecclesia must have numbered at least 50 people and probably more. • • • • • • some (but not many) of noble birth (1 Cor 1:26–28). Probably Erastus was one of them. some well off. 2 Cor 8:14. poor people. 1 Cor 1:28; 11:22. slaves. 1 Cor 7:21–23 Jews. 1 Cor 7:18. Two of whom were synagogue rulers—Crispus and Sosthenes. Gentiles 1 Cor 12:2 Does our own ecclesia mix reflect true diversity in our community? If not, how can we correct the imbalance? The met in homes (e.g., one group met in home of Aquila & Priscilla), and probably did not all meet together very often (see 1 Cor 14:23). In any case, it would have been impossible even for a wealthy member to accommodate more than 50 people in his home. All the archaeological evidence suggests there were no buildings designated for church meetings only until about 200 years later. For the first few centuries, home meetings were the standard. 2.4 Divisions in Corinth 1 Corinthians 1:11–13 Apparently they had started dividing up into groups based on which teacher they preferred. • Apollos: may have been favoured by the highly educated as he was the best orator. • Paul: may have appealed to the educated Jews who admired his skill in expounding the Old Testament. • Peter: as one of the original disciples, he would have attracted his own following. His adherence to the law would have appealed to the Jews. • Christ: you can imagine people saying they were not going to follow any ordinary man, they were followers of Jesus himself. But that sort of one-up-man-ship was inappropriate also. At least part of the problem was due to the Corinthians being concerned over the relative social status of Apollos and Paul. Paul was very well educated and extremely well-read—he could quote the famous Greek poets and writers. However, he was no orator. He describes himself as a weak speaker (1 Cor 2:1–4; 2 Cor 10:1,10; 11:6). This would have counted against him in a Greek city like Corinth. They placed great value on oratory and skilled oral rhetoric. It seems his letters showed great skill in the use of Greek rhetoric in writing, but that he was unable to speak to the same level of skill. Corinth: conflict and community 12 On the other hand, Apollos was clearly a great orator. See Ac 18:24–25,28. It seems Apollos was well aware of the tension because of his oratory skills and Paul’s lack of oratory skills (see 1 Cor 16:12). Apparently he was reluctant to visit Corinth, and I suspect it was due to the factions that had developed in Corinth. If he went, it could get worse. So he prefers another to go—namely Timothy (v10–11). This shows Apollos to be a person of great wisdom and humility. He could have taken the opportunity to go and enjoyed the acclaim that came with being such a great speaker, but he wisely thought better of it. Because of these difficulties over oratory, in the letters to Corinth there is a great deal of emphasis placed on godly wisdom as opposed to worldly wisdom. Paul was trying to explain to the Corinthians that their cultural values which rated oratory highly didn’t matter when it came to God. It is instructive that Paul chose to deal with this problem of division first (1 Cor 1:10). Remember, in Corinth there were lots of problems: gross immorality, chaos at the Memorial Meeting, misuse of the Spirit gifts, litigation amongst brothers, doctrinal errors, etc. But to God, division amongst brothers and sisters is one of the worst problems that can befall us. It is one of the few things that we are told deserves disfellowship (see Tit 3:10; Rom 16:17). Yet I wonder if we always treat it as seriously as that ourselves. We still can form factions if we are not careful, with people separating into groups associated with individual people, or even magazines. In the case of Corinth, Paul argues that the groups should all see themselves as part of one group working in harmony for Christ. We need to be careful of this. Those groups or ecclesias that see things differently from us are doing their own work in God’s service and can be just as valuable as the way we choose to do things. Diversity is strength. Diversity is not disunity. I planted the seed, Apollos watered it, but God made it grow. So neither he who plants nor he who waters is anything, but only God, who makes things grow. (1 Cor 3:6–7) 2.5 Division and the Lord’s Supper 1 Corinthians 11:17–22 There are two issues here—they were treating Lord’s supper like an ordinary meal, and they were not allowing everyone to eat equitably. Of course, the Lord’s supper was originally a full meal, not just bread and wine. For a while, it seems, the early Christians followed this practice and had a full meal together during which they took the bread and wine. It was called a love feast or agapé meal. See Jude 12. It was normal custom for dinner hosts to serve wealthy merchants in one room with one kind of food, and the poor and slaves in another room with the leftovers. It seems highly likely that this was taking place in the Memorial meeting (v22). Corinth: conflict and community 13 In some ways I think it is a pity that it became necessary to separate the Bread & Wine from meals. I have once had a meal with friends where we had the Bread & Wine as part of the meal and it was a very nice occasion. But Christians in general have not done this since the first century because of the problems that developed in Corinth and elsewhere. Note that the Memorial Meeting in Corinth was not a closed occasion. See 1 Cor 14:23. Maybe they showed up to get a free meal. Maybe they were interested in what was going on. Maybe they had been invited as a preaching method. Paul doesn’t condemn it, and seems to treat it as a useful preaching occasion. Should we? 2.6 Questions 1 What social divisions exist in Australia that can spill over into the ecclesia? 2 Do some of our members feel like “second-class” citizens? How can we overcome this? 3 How can we avoid factions in our ecclesias? Corinth: conflict and community 14 3. You are still worldly Reading: 1 Corinthians 8 3.1 Problems facing the Corinth ecclesia • • • • • • • Division and attachments to particular teachers Lawsuits Sexual immorality Dining in pagan temples Unequal treatment at Lord’s supper Misuse of spirit gifts Disagreement over some doctrines Remember, many of these people had come from a life of paganism and idolatry, and the sudden change of lifestyle was very difficult for them. It is still difficult. When a person goes from a life of drinking, smoking, swearing and immorality, to a life in Christ, it is hard. The old habits don’t die away immediately. They must be fought and overcome. This was probably even more so in Corinth because there was no stable ecclesial environment that the new members could join. They were all new. Nobody had a background in the Truth. Nobody quite knew how to organize an ecclesia, or what was expected. Nobody had experience in handling problems when they arose. People were unclear which parts of their old life had to be given up, and which parts were ok to continue. We don’t face these problems today in Australia. Almost everyone who is baptised is able to join an established ecclesia and enjoy the benefit of meeting with people who have had the experience of ecclesial life and who have the collective wisdom in knowing how to handle problems that arise. However, the same problems are occurring in other parts of the world where there have been many baptisms in a town but no experienced brothers there to guide the new converts. Of course, there are disadvantages with long-established ecclesias too. People become bound by tradition, are less accepting of new ideas and new approaches, and can lose their first love. New converts enliven an ecclesia and bring fresh enthusiasm and ideas. Corinth had the benefit of Paul’s presence for the first 18 months, then they had his advice by letter after that. We learn most about the problems they encountered through Paul’s letters, especially 1 Corinthians. Apart from doctrinal disagreement, all the problems probably stem from their culture and customs before baptism. So we need to understand the social environment in order to really appreciate what Paul is dealing with, and so we can see more clearly how to draw conclusions that are relevant for our modern context. Corinth: conflict and community 15 Although Corinth was an ecclesia riddled with problems, it is worth noting that Paul did not disfellowship them, or give up on them. He wrote more often to them than to any other ecclesia as far as we know. He spent more time with them then most other ecclesias. He sent people to help them. 3.2 Meat offered to idols 1 Corinthians 8 Prior to this, the apostles had decided that believers should not eat meat offered to idols (Acts 15:23–29). Presumably, this advice had also been taught to new ecclesias as they became established, including the church in Corinth. I suspect that there were people in Corinth who were rejecting this rule and were choosing to go to the pagan temples for meals. Not for worship but for meals. You see, attached to the temples were restaurants where you could eat the food that had been offered to the gods. There is archaeological evidence at one of the temples in Corinth of a dining room with couches along the four walls and a fire place in the centre. The temple was an important place to do business, and maintain social contacts, and although the Christians would no longer worship there, there were probably some who thought there was no harm in eating at the restaurant. Paul deals with this by first acknowledging the correctness of their argument (v4,7–8). They were right in saying it would do no harm to eat the meat—it was only food after all. However, by eating, they might be leading other people astray, because some weaker people might see them eating the temple food and be encouraged to slip back into full temple worship. So he argues that it is better not to eat at all then to cause someone else to sin. He states it more strongly in 10:18–22. Here it is clear that eating temple food is strictly forbidden. Apart from the association with pagan idolatry, temple worship often involved sexual entertainment. It was like a restaurant with a stripshow. And obviously no Christian could be at such a place, even without the food problems. On the other hand, some food from the temple was later sold in the market place (see 1 Cor 10:27–30). Paul judges that it was ok to eat the food provided no-one discussed where it came from. But if someone mentions it, it is better not to eat because of the association. The key principle is: avoid doing anything that might lead your brother into sin. The tyranny of the offended 1 Cor 8:13; cf NIV. Similarly Rom 14:21. The word offence means “stumble” or “fall away”. It is talking about leading people to sin. It has nothing to do with personal preferences. The verse does not say “If someone gets their nose out of joint because of what you do . . . ” It says “If someone falls from the truth because Corinth: conflict and community 16 of what you do . . . ” Too often these verses have been quoted to support an unscriptural position. People say “I’m offended by that type of music” or “I’m offended by that clothing”. Unless they mean, they are likely to sin as a result, they are using the words in a different sense from what the Bible means. Because people don’t like something, they claim they are offended and expect everyone else to do what they want as a result of these verses. That is not what the verses allow. A correct modern analogy would be going to a pub for a beer. There is nothing wrong in it (provided you don’t get drunk). But if by going you lead other brothers or sisters to take up drinking to excess, then you are causing offence in the biblical sense. 3.3 The problem of tongue speaking Tongues of angels This was a term used by the liberal Jewish sect the “Therapeutae”. One of their writings was the “Testament of Job”. It describes “tongues of angels” apparently referring to glossolalia. Testament of Job, 49:1–50:3. o o o o • • • • • “. . . she chanted a hymn to God in the hymnology of the angels.” “. . . her mouth received the dialect of the angelic principalities . . . ” “. . . her mouth chanted in the dialect of those on high.” “. . . she spoke in the dialect of the cherubim.” Glossolalia is the phenomena of ecstatic gibberish found in many religions. It is practiced by Pentecostal churches today (who claim it is the gift of tongues). See 1 Cor 13:1; 14:7–9, 14–15, 19. Paul is saying that the tongues in Corinth were not intelligible. 100 years later there is strong evidence of glossolalia. Could it be that part of the Corinthian problem was that some people were mistaking glossolalia for a true gift of tongues? Glossolalia in the 2nd century • AD 160: Montanus, (Eusebius History 5:16) • AD 140: Marcus, (Iranaeus, Against Heresies 1:14) • Pistis Sophia 4.142 For more discussion of this problem in Corinth, see “Tongues of angels”, by Br Steve Cox. Corinth: conflict and community 17 3.4 Chaotic meetings 1 Corinthians 14:26–40 Picture is one of chaos. • People calling out spontaneously. • People speaking at the same time as others are speaking • No organization or order to the meeting See 1 Cor 14:29. People need to evaluate what is being said. This suggests that the prophecies were not like OT prophecy which had divine authority. Here the idea seems to be that people who considered themselves prophets would stand and say whatever it was they wanted to share with the congregation. As they spoke, others in the congregation would judge whether what they said was really coming from the Lord. This was done by someone who had the gift of discerning spirits (1 Cor 12:10). The people who were judging what was being said would have been asking questions of the one prophesying to determine if it was a genuine Spirit-inspired message. So Paul’s first point is get some order into proceedings or it is largely a waste of time. v39–40. To understand the passage more fully, we need to understand how the Corinthians would have viewed prophecy. • Apollo was the god of prophecy and his temple was the largest in Corinth. So they were very familiar with the Greek concept of prophecy. • About 50 km away was the town of Delphi where the most famous Greek prophet of all lived. She was known as the Delphic oracle and people from all over the Roman world would come to Corinth. Apart from the main prophetess, there were also other prophets who were based in Delphi. • People would come to Delphi to ask the oracle questions. In fact, it seems she wouldn’t speak without questions. So people would ask all sorts of questions including personal questions such as about one’s birth or origin, career, or profession, whether one should buy some land, and about death and burial. One of the most frequent sorts of questions according to the descriptions that survive were those about marriage and childbearing. It seems likely that the Corinthian view of prophecy was coloured by this Greek concept with which they would have all been very familiar. Corinth: conflict and community 18 Delphi, Greece Corinth: conflict and community 19 Women speaking 1 Cor 14:34–40 Note context: this comes at end of section on prophecies and tongues and he continues with prophecies and tongues in v37–40. So whatever we make of v34–35, it needs to be understood in this context. It refers to the chaotic nature of their assemblies and the unrestrained use of the Spirit gifts, or alleged gifts. First let’s be clear what it doesn’t mean. It does not mean that women were unable to speak at all. Paul didn’t mean they should never speak because he specifically allows that in 1 Cor 11 (“every woman who prays or prophesies with her head uncovered dishonors her head”). He even allows prophecy which involved teaching, provided it was done with the head covered. So what is described here in ch 14 must be different in some way. If they were allowed to pray and prophesy, what did Paul mean when he said they should not ask questions? I think it probably relates to the contemporary practice of asking a prophet lots of personal questions. They were used to doing this with the prophets of Apollo, and it seems they thought Christian prophets could be used in the same way. Paul says that a memorial meeting is not to be turned into a question and answer session. They should not ask such questions in the meeting. Personal questions are to be discussed at home. So in this one aspect of the meeting, he says women should be silent. But, in my opinion, he does not say they should be silent in praying, prophesying, speaking in tongues, singing, or other aspects of the service. He is saying they should be silent when it comes to asking the prophets questions as it is disruptive and inappropriate. 1 Cor 14:35. husbands = “their men”. i.e., the men of their house. Probably means they can discuss questions at home, but not in the church. 3.5 Conclusion There are many lessons for us in these things, even if the particular problem or cultural practice has long since disappeared. What is important for us to learn is how to solve these problems. • Paul’s approach is not to disfellowship, but to patiently instruct as we saw in the division problem. • He does not make rigid rules but is flexible as was seen in the meat offered to idols problem. • He doesn’t stifle people’s enthusiasm, even if they are incorrect, as we saw in the tonguespeaking problem. • And even with disorderly meetings, he doesn’t lay down rules for how a meeting should be conducted. He allows the church to do it the way that suits them, provided it is orderly and helpful for all attending. Corinth: conflict and community 20 In all, it is a remarkable lesson in how we should handle things with gentleness, and with a clear vision of what is important and what is not. The body is a unit, though it is made up of many parts; and though all its parts are many, they form one body. So it is with Christ. For we were all baptized by one Spirit into one body—whether Jews or Greeks, slave or free—and we were all given the one Spirit to drink. Now the body is not made up of one part but of many. . . so that there should be no division in the body, but that its parts should have equal concern for each other. If one part suffers, every part suffers with it; if one part is honored, every part rejoices with it. Now you are the body of Christ, and each one of you is a part of it. (1 Corinthians 12:12–14,25–27) 3.6 Questions 1 What problems do our new converts have in adjusting to a life in Christ? What can we do to help them? 2 Under what circumstances is 1 Corinthians 8:9 relevant today? 3 Are you convinced by Rob’s explanation of 1 Corinthians 14:34–35? If not, what alternative explanations do you have that (a) are consistent with 1 Corinthians 11 and (b) are consistent with the context of prophecy? Corinth: conflict and community 21 4. Super apostles! Reading: 2 Corinthians 10:1 – 11:15 One of the major themes of 2 Corinthians is Paul’s defence of his own authority. Some false teachers had come into the ecclesia at Corinth and were challenging Paul’s authority. It seems they claimed he wasn’t a real apostle, and he was not entirely trustworthy, and Paul was forced to defend himself. Some Corinthians were disputing Paul’s: • • • • legitimacy as an apostle of Jesus (2 Cor 13:3) ability to speak (2 Cor 10:10) holiness and sincerity (2 Cor 1:12–14; 7:2) lack of integrity in travel plans (2 Cor 1:15–17) Cf. NET (2 Cor 1:17) Therefore when I was planning to do this, I did not do so without thinking about what I was doing, did I? Or do I make my plans according to mere human standards so that I would be saying both “Yes, yes” and “No, no” at the same time? 4.1 False apostles At the same time, there were false apostles who had arrived in Corinth and were discrediting Paul. We can piece together a picture of the false apostles from references in 2 Corinthians. • • • • • • • • • Paid preachers Trained preachers Wanted to be considered equal or superior to Paul Carried letters of recommendation Used deception and distortion Took pride in human position Commended themselves Jewish Christians Belonging to Christ (2 Cor 2:17; 2 Cor 11:7) (2 Cor 11:7) (2 Cor 11:12–13; 12:11–13) (2 Cor 3:1) (2 Cor 4:2) (2 Cor 5:12) (2 Cor 10:12) (2 Cor 11:21–22) (2 Cor 10:7) The same problem occurred in other ecclesias as well. See Gal 2:4–6,12; 4:17; 2 Thess 2:1–2; 3:17. Acts 21:20–21.; Php 1:15–17; 2 Tim 1:15; Tit 1:14; 1 Tim 2:7. 4.2 Paul’s credentials and suffering Read 2 Cor 6:4–10; 2 Cor 11:16–28. Corinth: conflict and community 22 Why does Paul say all this this? It was part of his defence of his apostleship. The catalogues of suffering show that he has not only endured, but that he has kept his integrity in tact throughout. They demonstrate that he has pure motives as an apostle and is not just in for money or power or any such worldly ambitions. 4.3 The man with a vision 2 Corinthians 12:1–6. The first thing to look at here is “who had this vision?” I am convinced it was Paul himself. It comes in the middle of his extended defence of his apostleship. All of chapters 10 and 11 involve establishing his credentials as an apostle. In chapter 12 he says he is still boasting (12:1) and in 12:7 he says it was himself who had these revelations. We know he is still talking about his credentials in 12:11. It also seems likely that the false apostles had made claims to visions and revelations themselves to support their positions. And Paul needs to resort to explaining his own credentials. So he tells a story that he had never told anyone before. So why does he switch in v2–5 to refer to the visions as if they belong to someone else? It seems he was feeling very uncomfortable with all this talk about his own authority and credentials, and for this particular incident he used the third person. See 12:5. So what happened to him? Obviously it was a vision of God’s throne or something similar. Maybe similar to what Isaiah saw when he said “I saw the Lord seated on a throne, high and exalted, and the train of his robe filled the temple.” (Isa 6:1) Also Moses and Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, and the seventy elders of Israel — they “saw the God of Israel. Under his feet was something like a pavement made of sapphire, clear as the sky itself.” (Ex 24:10) Or Ezekiel who says “the heavens were opened and I saw visions of God.” (Eze 1:1). The third heaven is probably a reference to the old Jewish idea of three places called heaven: 1 atmosphere: where birds fly 2 outer space: where stars are 3 spiritual realm: where God lives. Third heaven also called “highest heaven” to distinguish from others. He quickly goes back to discuss his weaknesses in v7 where he is obviously more comfortable. The point of this all is his own authority as an apostle, and to counteract what the false apostles were saying about him — 2 Cor 12:11–12. Corinth: conflict and community 23 5. My power is made perfect in weakness Reading: Acts 18:1–17 5.1 Paul’s fears Acts 18:9–10. Why did the Lord say this? It must have been that Paul was fearful. Why was he fearful? Compare: • • • • Acts 17:14–15; 1 Thessalonians 2:1–2; 2:14–3:5. 1 Corinthians 2:3 2 Corinthians 1:8–9; 2:12–13; 7:5–6; 12:7–10. It seems he was afraid to speak/preach due to Jewish opposition. He may have been suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. The Lord was promising to protect him due to his temporary frailty. 5.2 Paul’s thorn in the flesh It is also clear from the above verses that this was Paul’s “thorn in the flesh”, his Satan. It was sent for a purpose: But this happened that we might not rely on ourselves but on God, who raises the dead. He has delivered us from such a deadly peril, and he will deliver us. On him we have set our hope that he will continue to deliver us, as you help us by your prayers. (2 Corinthians 1:9–11) there was given me a thorn in my flesh, a messenger of Satan, to torment me. Three times I pleaded with the Lord to take it away from me. But he said to me, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” Therefore I will boast all the more gladly about my weaknesses, so that Christ’s power may rest on me. That is why, for Christ’s sake, I delight in weaknesses, in insults, in hardships, in persecutions, in difficulties. For when I am weak, then I am strong. (2 Corinthians 12:7–10) Corinth: conflict and community 24 5.3 God’s power is made perfect when we are weak Other examples: • • • • • • Widow of Zarephath (1 Kings 17:7–16) Israel in the wilderness (Exodus 15:22–27; Deut 8:2–3) People of Malachi’s day (Mal 3:10–11) Moses in Midian David in Judean wilderness Peter after rooster crowed I think this is what is meant by the Lord’s discipline. Heb 12:5–11 We tend to think of discipline as punishment. Although discipline can involve punishment, I don’t think that is what is intended here. The woman of Zarephath wasn’t being punished when she gave up her oil and flour. Abraham wasn’t being punished when he was asked to offer Isaac. Jesus wasn’t punished by the constant threats on his life. No, in each case God was disciplining his people by making their lives difficult to teach them a lesson. God sent a famine on Canaan when Abraham was living there. He must have been disappointed when Abraham decided to go to Egypt instead of trusting God to provide. He sent the same test a few years later and Abraham failed the test again. I wonder what tests he has sent me or you which we have failed and disappointed our heavenly Father. I wonder when he has smiled broadly in pleasure at seeing me or you learn a new spiritual lesson through circumstances he arranged in our lives. I believe we need to think in this way, and look at circumstances in our lives to see what lessons God is teaching us. Unless we think like that, we are likely to miss the point he is teaching us. The hardest thing in these tests is learning not to rely on your own strength. Paul had difficulty learning this lesson and during his second missionary journey, it appears God made his life very difficult. He was under extreme persecution from the Jews until he learnt not to rely on himself. Once he had given up hope of solving the problem himself, then he had overcome it. In his weakness, he was strong. God wants people to trust him enough to put their lives in his hands. He can use us if we do things where we are relying on his refuge. If we are going to be much use to God, we need to be prepared to do things which are, perhaps, ‘risky’. And if we are going to learn the lessons he is teaching us, we need to be prepared to throw ourselves on his mercy and allow him to be our refuge. Corinth: conflict and community 25 6. Conclusion The first few years of the Corinth ecclesia were difficult. The new Christians were young and immature, fighting off their backgrounds in idolatry and immorality, and learning to get along with each other despite the social and economic differences. They had many difficulties to overcome including factions and divisions their interaction with temple worship the sexual problems that arose at least partly due to their previous pagan worship the misuse of the Spirit gifts the infiltration of the ecclesia by false prophets who sought to undermine Paul who had taught them • questions about how to deal with problems within the ecclesia including marriage, legal disputes, how to run their meetings, leadership, etc. • • • • • Through all this, Paul patiently instructs them and exhorts them through the two letters that have been preserved for us. He must have been extremely frustrated at times. In fact he says so: “I face daily the pressure of my concern for all the churches.” (2 Cor 11:28). And probably for the Corinth church more than them all. He describes 1 Corinthians: “For I wrote you out of great distress and anguish of heart and with many tears, not to grieve you but to let you know the depth of my love for you.” (2 Cor 2:4). The depth of his love shines through, as does his distress and anguish and love of the Truth. Let’s conclude as Paul does: Finally, brothers, good-by. Aim for perfection, listen to my appeal, be of one mind, live in peace. And the God of love and peace will be with you. Greet one another with a holy kiss. All the saints send their greetings. May the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, and the love of God, and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all. (2 Corinthians 13:11–14)