Developing a Roadmap for the Future of National Hazardous Substances Incident Surveillance

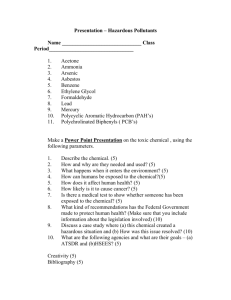

advertisement