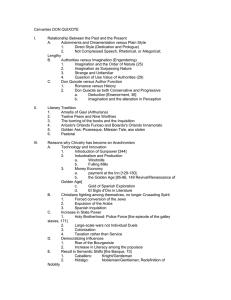

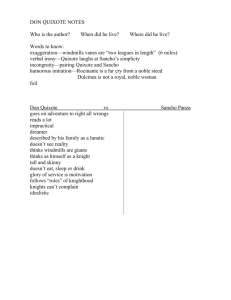

21L.472 Major European Novels MIT OpenCourseWare Fall 2008 rms of Use, visit:

advertisement