Antitrust Law Journal N E

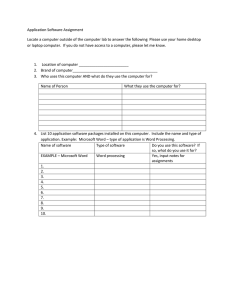

advertisement