REVIEW OF INTER-PARLIAMENTARY UNION’S GENDER PROGRAMME ‘PROMOTING GENDER EQUALITY IN POLITICS’

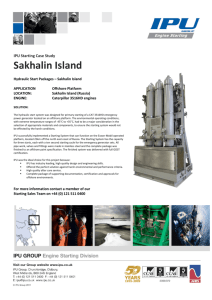

advertisement