The Missing Link – bridging between social movement theory and... A GARNET Working Paper No: 60/08

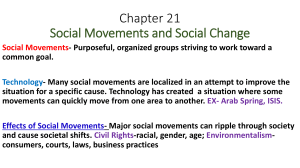

advertisement