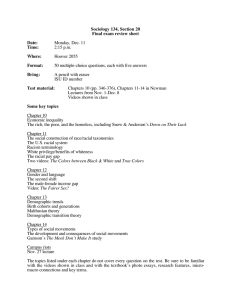

An Abstract of the Dissertation of

advertisement