TOWN OF HANOVER AFFORDABLE HOUSING FEASIBILITY STUDY July 2001 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

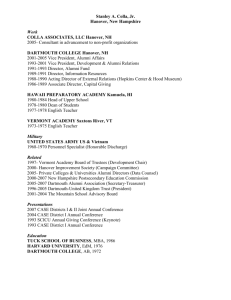

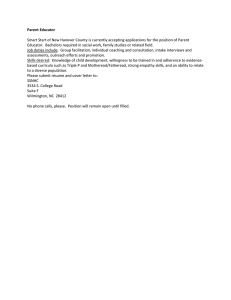

advertisement