A SYSTEMS MODEL OF THE POST-DILUVIAL EXPANSION OF THE NATIONAL

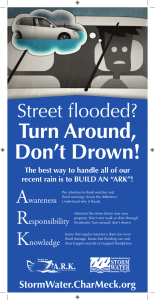

advertisement