Document 13561361

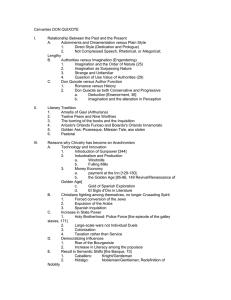

advertisement