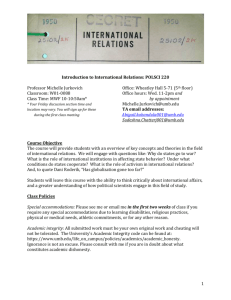

PLSC 212 Introduction to International Politics Eastern Michigan University

advertisement

PLSC 212 Introduction to International Politics Eastern Michigan University Winter 2015 CRN: 20333 T & Th, 9:30-10:45 p.m., 420 Pray-Harrold Dr. Judith Kullberg Office: 601-S Pray-Harrold Telephone: (734) 487-1405 or (734) 487-3113 Office hours: T & Th. 1-3 p.m. and by appointment Email: judith.kullberg@emich.edu Course Description We live in an increasingly interdependent world, in which events and trends in any country or region directly or indirectly affect people around the globe. Much of this interdependence is the result of economic globalization, the merging of separate national economies into a single integrated global economy in which multinational corporations (MNCs) freely move capital, operations, and goods across national borders. The effects of economic globalization have been mixed: considerable dislocation of workers and low rates of economic growth in Europe and the U.S., increased income inequality within and between countries, but also rapid technological innovation and rising standards of living in newly industrialized countries such as China and India. The emergence of new middles classes in once poor nations has increased demand for natural resources and commodities such as oil, natural gas and food, driving prices higher and increasing the cost of living around the world. As traditional cultures and ways of life in less developed nations are disrupted by the advancing global economy, millions of people migrate each year in search of opportunities. The massive movements of capital, goods, and people around the planet are supported by a communications network that allows for instantaneous transmission of enormous amounts of data. Against this backdrop of increasing global integration, humanity is facing serious, even existential threats. Some of these threats arise from the current pattern of economic development, which is clearly unsustainable. Population growth, rising standards of living, and constantly increasing consumption are straining the earth's natural resources and ecosystems, causing widespread environmental degradation and global climate change. Other threats, such as ethnic conflict and war, are ancient; however, the lethality of the weaponry used in modern warfare is tremendous. Nuclear weapons that originated in the most scientifically and technologically advanced nations (the United States and the former Soviet Union) during the Cold War era are now also in the possession of several less developed and politically unstable nations, such as North Korea and Pakistan, and are likely to be soon acquired by Iran as well. It is also conceivable that nuclear weapons, as well as chemical and biological weapons (all of which are referred to as "weapons of mass destruction," WMD), could fall into the hands of terrorist organizations. Whether or not humanity can successfully respond to the threats and challenges of the 21st century will largely depend on the ability of the nations of the world to cooperate and collaborate. Although there is no world government, there is an international system that allows for some degree of governance. The primary elements of this system are 194 separate states. The primary structure bringing them together is the United Nations, an international organization established in 1945 to enhance international security, facilitate cooperation, further economic development, and strengthen human rights. The United Nations, its agencies, and courts have increased international cooperation in many areas, and a growing body of international law has stabilized the contemporary world. In addition to the UN, there are thousands of other international non-governmental and governmental organizations, each established for particular purposes. These organizations collaborate with other organizations and states to achieve their goals. Despite the high level of organization of the contemporary international system, individual states often act unilaterally to enhance their security and pursue their particular national interests. Many still seek to constantly expand their power and to dominate other states. In sum, contemporary international politics is characterized by both cooperation and competition. This course will provide you with theories and concepts that will help you to understand and analyze the complex mosaic of contemporary world politics. It will introduce you to the major approaches in the study of international relations, a field within the discipline of political science. We will explore the changing nature of the international system, the causes of war and interstate conflict, the factors that influence foreign policy decision-making, and the determinants of economic development. In addition, we will examine a range of problems and controversial issues, such the desirability of free trade and economic globalization, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the response to international terrorism, the role of international law and institutions in protecting fundamental human rights, and the causes and consequences of global poverty. Course Objectives The primary objective of the course is that you deepen your understanding of international relations (IR). You will acquire a good grasp of basic concepts used in the study of IR. You will also become familiar with the major theoretical perspectives used in the study of IR. You will be able to identify and discuss major historical events that shaped the contemporary international system. You will also acquire a good understanding of that system and the structure and role of international institutions, particularly the United Nations. You will use all of this knowledge to analyze current international issues and events and to develop your own perspectives. Finally, you will be encouraged to consider your own role and responsibilities as a member of the global community. General Education Rationale PLSC 212 satisfies the "Knowledge of the Disciplines: Social Science" requirement of the EMU General Education curriculum because it emphasizes how political scientists acquire and share knowledge about the world. The course requires students to use the theoretical frameworks of the study of International Relations (IR) -- including realism, neo-realism, liberalism, and feminism -- to pose and address questions about contemporary issues and problems, including interstate disputes and wars, economic globalization, the increasing inequality among rich and poor nations, protection of human rights, threats to environmental quality and population growth. Through examination of research on such topics, students become familiar with the process of social science research and acquire the ability to critically evaluate research designs and the results from research. The course also provides students an opportunity to gather, examine, and interpret data, and to report the findings of their research, thus contributing to their understanding of how inquiry is conducted and knowledge is disseminated in political science. In sum, the course prepares students for citizenship in a global community by not only giving them basic factual knowledge of international relations and global processes, but also by providing them with the tools necessary to understand and explain international events and global patterns of change. General Education Social Science Objectives In this course, you will: Acquire an understanding of social science methods and how they are used in the systematic study of international politics as well as interactions between societies and cultures. Understand and compare the formal and informal social and political structures, organizations and institutions that comprise the world system. Explore power relationships among states and the ways in which changes in the global system across history have affected the developmental trajectories of nations and the life experiences of their citizens. Use social science methods to conduct research on topics in international relations and to make informed decisions regarding international issues. Learn the differences between qualitative and quantitative data. Clearly and concisely present the results of research, using both qualitative and quantitative data. Readings The required reading for the course will primarily come from the textbook below. It can be purchased at the bookstore in the EMU Student Center or online booksellers such as Amazon.com. Another option is to purchase access to the digital format at less than half the publisher’s retail price (http://www.coursesmart.com ). Joshua S. Goldstein and John C. Pevehouse, International Relations (Pearson), Brief 6th edition, 2013-14 update (ISBN:978-0-205-07143-5). All other required readings listed on the syllabus can be found on the course eCollege companion website (http://www.emuonline.edu), either under “Docsharing” or “Webliography.” In addition, I will occasionally assign short news articles that are directly related to the themes of the course. I will distribute these articles in class and/or post them on eCollege. Course Requirements Students are expected to: Read and think! The surest route to a good grade in this class (or any class) is to complete the assigned reading. You should complete the reading before the class for which it is assigned. The reading will introduce you to basic concepts and theories of international relations, challenge you to think critically about current issues, and encourage you to develop your own reasoned judgments on these issues. Lectures, discussions, films, and activities in class will reinforce the knowledge you acquire through reading, but they are not a substitute for reading. Your mastery of the course concepts and factual information provided in the readings and lectures will be assessed through quizzes, in-class activities, and exams (see below). Attend Class and Participate Class attendance and participation are strongly correlated with learning and performance. You should attend regularly and when present, pay attention and participation in discussion. To help maintain focus and enhance retention of course concepts, you should also take notes during lecture. To encourage you to attend class, I will award up to 100 points for attendance and participation, depending on the percentage of class sessions you've attended and the quality of your participation. Not including exam days, there will be 28 class sessions in the term, which means that attendance at each class is worth approximately 3.57 points. Occasionally, points will be based on an in-class quiz, activity, or your notes on that day’s lecture, which I will occasionally collect at the end of class. Use the course eCollege site and check your email I have created a companion eCollege webpage at www.emuonline.edu . All information necessary for class (except for the textbook), including the syllabus, assignments, lecture powerpoints, relevant videos and supplemental readings will be available on the eCollege site. The companion site also has links to ancillary materials from the textbook publisher, including downloadable podcasts and practice tests. In addition, you will submit assignments using the dropbox on the site and I will return them to you through the companion site. Scores will also be posted in the online course gradebook. Finally, all course announcements will not only be emailed to you (you should check your email regularly), but also posted on the companion site. Follow world affairs To achieve the greatest benefit from this course, you should follow the international news. Recommended news sources include The New York Times andThe Washington Post (available online); periodicals such as The Economist or The Nation; and radio news broadcasts such as the noncommercial Free Speech Radio News (online at http://www.fsrn.org or broadcast on WCBN, 88.3 FM, 5:30-6:00 p.m. Mon.-Fri.); National Public Radio (online athttp://news.npr.org or on the hour at WEMU, 89.1 FM or WUOM, 91.7 FM); and BBC news (online at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world or broadcast on WUOM, 91.7 FM, 9:00-10:00 am, Mon.-Fri.). As noted above, I will occasionally distribute news articles and these will be considered part of the required reading. Research Over the course of the term, you will complete and submit two short, 3-5 page research papers. These will involve analysis of some aspect of international relations using various kinds of information, including simple statistics. Each research assignment will be worth 100 points. The first paper will be due January 27 and the second March 26. Both assignments will be distributed two weeks before the due date. Debate During the semester, we will hold four informal debates on current issues in international affairs. Each student will participate in two debates as a member of a 3-person team. These debates will require considerable preparation in the form of research and acquisition of firm knowledge of the topic under consideration. Teammates, the audience, and I will assess the quality of each participant’s contribution to the debate. Debate participation will be worth 50 points each (100 points total), which is approximately 17% of the final course grade. Guidelines and rubrics for the debates will be distributed in class and posted on the course reserves web site early in the semester. The makeup assignment for those unable to participate in the debate (with an excused absence) will be a 4-5 page paper that succinctly presents your team’s argument. Take Exams Mastery of course concepts will be primarily assessed by means of a midterm exam (February 19) and a comprehensive final exam (April 23). The midterm will be worth 100 points and the final 150. Exams will be composed of a mix of short answer and essay questions. A study guide will be posted on the eCollege site a week prior to each exam. Grading Scale The total number of possible points that you can earn on the assignments, the debate, quizzes/activities, and exams is 650. The course grade will be based on the percentage of the points earned, according to the following scale: 605-650 A 585-604 A566-584 B+ 540-565 B 520-539 B500-519 C+ 475-499 C 455-474 C434-454 D+ 410-433 D 390-409 D0-408 F Late Assignments and Makeup Exams Except in cases of serious illness or family emergency, late assignments will not be accepted. When requesting an extension on an assignment, you must document the illness or emergency. Similarly, if you cannot participate in a debate or take an exam at the scheduled time due to a university-excused absence, illness, or emergency, you must contact me prior to the debate or exam to reschedule, along with an official excuse or evidence of the situation. Makeup exams will be in allessay format. Classroom Etiquette We will be considering many controversial issues during the semester and much class time will be devoted to discussion of these issues. In order to have an open and interesting exchange of ideas, we all must respect the right of others to express their views. Interruption when another person is speaking, disparagement of the ideas or views of others, and any other behavior that disrupts the class or interferes with the exchange of ideas will not be tolerated. Electronic Devices During class, cellphones should be turned off or muted and placed in book bags or pockets. Laptops can be used in class, but only for the purpose of taking notes. Academic Dishonesty Plagiarism -- the unacknowledged use of the words or ideas of another person as one's own -- is forbidden by the EMU Code of Student Conduct. Any assignment that is plagiarized, even in part, will receive a score of zero. Similarly, cheating on an exam is forbidden and will also result in a zero score on the exam. Any form of academic misconduct will also be reported to the Office of Student Conduct and Community Standards. A handout on plagiarism will be distributed in class with the first research paper assignment and posted on the course eCollege site. Schedule of Topics & Readings January 6 Overview of the Course January 8 Problems and Concepts in the Study of International Relations Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 1, pp. 1-19 (up to “Global Geography”) January 13 Geography, History, and the Changing International System Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 1, pp. 19-33. Elbridge Colby and Paul Lettow, “Have We Hit Peak America?: The Sources of U.S. Power and the Path to National Renaissance,” Foreign Policy, JulyAugust 2014, 54-63. January 15 Realism Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 2, "Realist Theories," pp. 35-49 (up to “Alliances”) John J. Mearsheimer, “Why the Ukraine Crisis is the West’s Fault: The Liberal Delusions that Provoked Putin,” Foreign Affairs (September-October 2014), 77-89. January 20 Realism: Alliances, Strategy, and Game Theory Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 2, pp. 49-60 Robert M. Citino, “The War that Wasn’t,” Military History (January 2015), 3443. January 22 The Critique of Realism, Part I: Liberalism and Social Theories Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 3, pp. 63-71 (up to “Domestic Influences”) Miriam Gomes Saraiva, “The Brazilian Soft Power Tradition,” Current History (February 2014), 64-69. January 27 The Critique of Realism, Part II: Marxism, Peace Studies, Feminism Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 3, pp. 86-104 James Whitehead, “Peace Studies: An Alternative Perspective on International Security,” E-International Relations, (August 30, 2013). January 29 & February 3 Domestic Influences and Foreign Policy Goldstein & Pevehouse, Chapter 3, pp. 71-86 David Rothkopf, “National Insecurity: Can Obama’s Foreign Policy Be Saved?,” Foreign Policy, September-October 2014. Film: Bush’s War February 5 War: Causes and Consequences Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 4, pp. 107-113 Jean-Marie Guehenno, “10 Wars to Watch in 2015,” Foreign Policy (January 2, 2015). Yochi Dreazen, “Tour of Duty,” Foreign Policy (September-October 2014), 5259. February 10 Conflicts of Ideas and Interests Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 4, p. 113-136 (up to “Conventional Military Forces”) James Traub, “The Lighthouse Dims,” Foreign Policy (November-December 2014). Thomas de Waal, “The G-Word: The Armenian Massacre and the Politics of Genocide,” Foreign Affairs (January-February 2015), 136-148. February 12 Military Force and Terrorism Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 4, pp. 136-149 Shamila N. Chaudhary, “In Pakistan, a New Focus for Counterterrorism,” Current History (April 2013), 152-54. February 17 Weapons of Mass Destruction Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 4, pp. 149-157 Scott D. Sagan, “The Future of the Nuclear Order,” Current History (January 2014), 23-25. February 19 ***Midterm Exam*** WINTER BREAK February 24 & 26, no class March 3 International Organization & the UN Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 6, pp. 207-226 (up to “The European Union”) James Verini, “Should the United Nations Wage War to Keep Peace?,” National Geographic (March 2014). March 5 International Law and Human Rights Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 6, pp. 240-255 “From Gaza to Ferguson: Exposing the Toolbox of Racist Repression,” Foreign Policy in Focus (August 2014). March 10 International Integration & the European Union Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 6, pp. 226-240 Matthias Matthijs and R. Daniel Kelemen, “Europe Reborn: How to Save the European Union from Irrelevance,” Foreign Affairs (January-February 2015), 96-107. March 12 Economic Globalization: Trade Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 5, pp. 163-181 Essays by Hills, Wilson and Castaneda on NAFTA, Foreign Affairs (January/February 2014), 122-141. Martha Burk, “How the TPP Sells Out America’s Women,” Foreign Policy in Focus (December 2014). March 17 Economic Globalization: The Monetary System, Finance, and International Business Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 5, pp. 187-202. Mark Blyth and Eric Lonergan, “Print Less but Transfer More: Why Central Banks Should Give Money Directly to the People,” Foreign Affairs(September-October 2014), 98-109. March 19 The North-South Gap Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 7, pp. 259-271 (to “Theories of Accumulation”) Angie Ngoc Tran, “The Vietnam Case: Workers versus the Global Supply Chain,” Harvard International Review (Summer 2011), 60-65. March 24 Causes of the North-South Gap Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 7, pp. 271-278 (to “Development Experiences”) Anirudh Krishna, “The Mixed News on Poverty,” Current History (January 2013), 20-25. March 26 Economic Development: Paths to Growth Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 7, pp. 278-289 (to “North-South Capital Flows”) Uri Dadush, “Converging Economic Destinies,” Current History (January 2014), 26-29. March 31 International Development: Capital Flows and Foreign Assistance Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 7, pp. 289-305 “Banker to the Poor: A Conversation with Jim Yong Kim,” Foreign Affairs (September-October 2014), 70-76. Maya Kroth, “Under New Management,” Foreign Policy (September-October 2014), 60-65 . April 2 The State of Planet Earth: Environmental Degradation and Climate Change Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 8, pp. 308-327 (up to “Pollution”) Judith Shapiro, “The Evolving Tactics of China’s Green Movement,” Current History (September 2013), 224-229. Oscar Reyes, “At the Lima Climate Talks, It Was Groundhog Day All Over Again,” Foreign Policy in Focus (December 2014). April 7 The State of Planet Earth: Pollution and Natural Resources Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 8, pp. 318-327 (to “Population”) Layne Hartsell and Emanuel Pstreich, “Peer-to-Peer Science: The Century-Long Challenge to Respond to Fukushima,” Foreign Policy in Focus (September 2013). April 9 The State of Planet Earth: Population, Disease, and Health Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 8, pp. 327-334 (up to “The Power of Information”) Thomas Insel et al, “Darkness Invisible: The Hidden Global Costs of Mental Illness,” Foreign Affairs (January-February 2015), 127-135. Laurie Garrett, “Sierra Leone’s Ebola Epidemic is Spiraling out of Control,” Foreign Policy (December 10, 2014). April 14 Technology and Globalization Goldstein & Pevehouse, Ch. 8, pp. 335-342 Shane Harris, “The Social Laboratory,” Foreign Policy, July-August 2014. April 16 Conclusion: IR and the Global Future Goldstein and Pevehouse, Ch. 8, pp. 342-344 Sharachchandra Lele, “Rethinking Sustainable Development,” Current History (November 2013), 311-16. Thursday, April 23 9-10:30 a.m. ***Final Exam***