Document 13556230

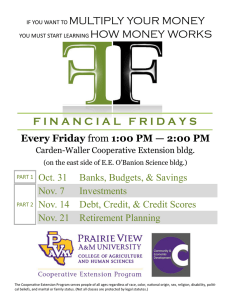

advertisement