Disturbed eating attitudes as predictors of coping processes and macronutrient... undergraduate females under stress

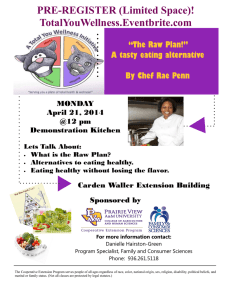

advertisement