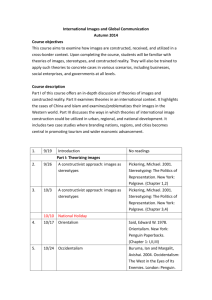

B R

advertisement

BOOK REVIEW The Foreign Policy of the European Union. By Stephan Keukeleire and Jennifer MacNaughtan. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. Pp. xvii+392. £ 22.99 (paper); £65.00 (hard); ISBN-10: 1403947228 (paper); ISBN-10: 140394721X (hard). Dr Christine Reh IPPR Volume 5 Number 1 (October 2009) pp. 85-90 © 2009 International Public Policy Review • The Department of Political Science The Rubin Building 29/30 • Tavistock Square • London • WC1 9QU http://www.ucl.ac.uk/ippr/ 93) !"#$%"&#!'"&()*+,(!-)*'(!-.)%$/!$0))))))1))))/'(2)34)"'2)5))1)))'-#',$%))6778)) ) ) BOOK REVIEW The Foreign Policy of the European Union. By Stephan Keukeleire and Jennifer MacNaughtan. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. Pp. xvii+392. £ 22.99 (paper); £65.00 (hard); ISBN-10: 1403947228 (paper); ISBN-10: 140394721X (hard). The external relations of the European Union (EU) have become a burgeoning topic of research and a popular subject of teaching: few European or international studies conferences do without a roundtable or panel on Europe’s global role; numerous research projects and academic networks generate a steady stream of publications on the topic; and courses on foreign policy are in high demand on European politics programmes, undergraduate and postgraduate alike. This academic interest stands in some contrast to the EU’s actual global actorness—unchallenged and acknowledged in world trade; active but less consistent when it comes to “mixed competences” such as environmental policy; criticised and contested with regard to crisis management and conflict resolution. Stephan Keukeleire and Jennifer MacNaughtan’s The Foreign Policy of the European Union was published in the European Union Series at Palgrave in 2008— almost a decade after the Amsterdam Treaty entered into force and with it a number of far-reaching institutional changes to Europe’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). The year 2008 also saw much activity in EU external relations—the launch of a military bridging operation in Tschad; the preparation of a rule of law mission in Kosovo; the breakdown of the Geneva ministerial meeting under the Doha trade round; agreement on a climate and energy package that not only committed the Union to cut its greenhouse gas emissions to at least 20% below 1990 levels by 2020, but pledged to increase the cut to 30% should other industrialised countries agree to do the same. In their book, Keukeleire and MacNaughtan cover the entire breadth of these activities: it is their declared aim to look at EU foreign policy beyond the narrow confines of CFSP and defence, and to assess how such policy can “shape and influence structures and long-term processes” worldwide.1 )))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))) 1 Keukeleire, S. and MacNaughtan, J. The Foreign Policy of the European Union (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008) p. 4. 9:) !"#$%"&#!'"&()*+,(!-)*'(!-.)%$/!$0))))))1))))/'(2)34)"'2)5))1)))'-#',$%))6778)) ) ) On a market already rich in textbooks, research monographs and edited volumes on the subject, The Foreign Policy of the European Union fills a niche in between theorydriven research monographs, such as Michael E. Smith’s institutionalist account of foreign policy cooperation in Europe2 and more basic introductions to the topic, such as Karen Smith’s European Union Foreign Policy in a Changing World 3; it covers wider substantive ground than Simon Nuttall’s excellent and comprehensive historical overview European Foreign Policy4 or Jolyon Howorth’s single-issue study Security and Defence Policy in the European Union 5; and it offers a welcome break from the dominant analytical focus on Europe’s identity as a global actor—be it “civilian”, “military” or “normative”—as developed prominently in Charlotte Bretherton and John Vogler’s The European Union as a Global Actor.6 In their volume Keukeleire and MacNaughtan pursue two objectives: first, “to provide an overview and analysis of EU foreign policy”, and, second, “to reappraise the nature of EU foreign policy and foreign policy more generally”7. The latter objective builds on their distinction between conventional foreign policy with its (alleged) focus on “states, military security, crises and conflicts”, and structural foreign policy, which “conducted over the long-term seeks to influence or shape sustainable political, legal, socio-economic, security and mental structures.”8 The authors develop their approach against the backdrop of a post-Cold War and globalising international context (chapter 1), as well as the historic development of EU foreign policy cooperation from the Marshall Plan to the Lisbon Treaty (chapter 2). They subsequently introduce Europe’s “foreign policy apparatus”9 in a systematic, detailed and accessible way: chapter 3 discusses the complex network of intergovernmental, supranational and bureaucratic actors behind EU )))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))) 2 Smith, M.E. Europe’s Foreign and Security Policy: The Institutionalization of Cooperation Perspectives (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004). 3 Smith, K.E. European Union Foreign Policy in a Changing World (Cambridge: Polity, 2008). 4 Nuttall, S. European Foreign Policy, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000). 5 Howorth, J. Security and Defence Policy in the European Union. (Houndmills: Palgrave, 2007). 6 Bretherton, C. and Vogler, J. The European Union as a Global Actor (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006). 7 Keukeleire, S. and MacNaughtan, J. The Foreign Policy of the European Union (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), p.3. 8 Ibid., p. 25. 9 Ibid., p. 329. 9;) !"#$%"&#!'"&()*+,(!-)*'(!-.)%$/!$0))))))1))))/'(2)34)"'2)5))1)))'-#',$%))6778)) ) ) foreign policy-making; chapter 4 turns from actors to processes, covering both de jure competences and decision-procedures and de facto policy-practices; while chapter 5 looks at the interplay between European and national foreign policies in both a bottom-up and a top-down perspective—a commendable exercise, given the much-discussed problem of vertical “consistency” or “coherence” in CFSP. The six remaining substantive chapters can be divided into two parts: chapters 6 to 9 are devoted to policies; chapters 10 and 11 cover issues of international cooperation. The first set covers “traditional ground”—CFSP (chapter 6) and European Security and Defence Policy (chapter 7); yet, true to the book’s aim of broadening our understanding of foreign policy they also introduce external policies located in the first pillar, including trade, development and the promotion of human rights (chapter 8) as well as internal policies with an external dimension, such as justice and home affairs or environmental policy (chapter 9). Following the discussion of three types of inter-regional cooperation—with potential member states; with neighbourhood countries; with Africa—in chapter 10, the penultimate chapter discusses cooperation with other “global ‘structural powers’”10 such as the US, China and Russia as well as the EU’s embeddedness in multilateral institutions. Chapter 12 concludes the book; unfortunately, it chooses to link the argument back to theories of European integration and International Relations more generally instead of focusing on the author’s potential contribution to foreign policy analysis. Throughout, the volume covers traditional textbook material in a systematic and accessible way; it also discusses less well-known aspects of EU foreign policy, such as the Council of Ministers’ substructure and the European Commission’s diverse Directorate-Generates11; the systematic cooperation between member states12; the external dimension of health and demography policies13; or the EU’s approach to international financial institutions14 and its relationship to “Islamism”.15 Hence, )))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))) 10 Ibid., p. 298. Ibid., p. 73. 12 Ibid., p.159. 13 Ibid., p. 249. 14 Ibid., p. 307. 15 Ibid., p. 322. 11 !"#$%"&#!'"&()*+,(!-)*'(!-.)%$/!$0))))))1))))/'(2)34)"'2)5))1)))'-#',$%))6778)) 99) ) ) Keukeleire and MacNaughtan certainly reach their first goal—their volume offers a comprehensive well-structured overview and analysis of EU foreign policy. The unusually broad approach taken, the wealth of information provided, the topical examples and up-to-date facts given in the text and additional tables as well as the further readings and sources suggested on the companion website make the book an accessible and readable resource for anyone researching, teaching and studying EU external relations. More scepticism is, however, in order when it comes to the authors’ second goal—to reappraise the nature of EU foreign policy beyond conventional wisdom. Indeed, the book’s twofold “conceptual backbone” 16 —the distinction between conventional foreign policy and structural foreign policy,17and the definition of EU foreign policy as “multipillar and multilevel, operating within a complex multilocational web of interlocking actors and processes” 18 —appeals for two reasons: it allows us to study foreign policy as an instance of multilevel governance, and it facilitates a potentially more fine-grained assessment of the EU’s performance than its usual broadbrushed condemnation (or praise) as (in)coherent or (in)effective. Yet, the framework suffers from a combination of overload and under-specification. First, the framework is overloaded because the authors identify no less than six research themes: the tensions between Atlanticists and Europeanists, between civilian and military power, between intergovernmentalism and supranationalism, and between external and internal objectives; the EU’s ambition to shape regional, national and global structures; and the EU’s struggle with power.19 These themes have not only been somewhat exhausted in the existing literature; their amalgamation also leaves the reader puzzling over what it is that the authors, ultimately, want to explain: the nature and trajectory of EU foreign policy? The way foreign policy decisions are reached? The distinction between the EU’s shortterm and long-term policy-goals and the reasons for reaching these goals? The Union’s structural influence? The book touches upon all of these questions, yet it answers none of them in systematic depth. Second, the framework is underspecified, because the authors )))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))) 16 Ibid., p. 34. Ibid., p. 25. 18 Ibid., p. 34. 19 Ibid., p. 8. 17 !"#$%"&#!'"&()*+,(!-)*'(!-.)%$/!$0))))))1))))/'(2)34)"'2)5))1)))'-#',$%))6778)) 98) ) ) fail to translate their definition of structural foreign policy into an analytical framework, and because they do not engage with the established literature on foreign policy analysis—conventional or not. According to Keukeleire and MacNaughtan foreign policy differs from external relations; the latter is about “maintaining relations with external actors”, the former “is directed at the external environment with the objective of influencing that environment and the behaviour of other actors within it, in order to pursue interests, values and goals.”20 If this is, indeed, the case then the reader would have expected a set of analytical tools that help her a) to identify such interests, values and goals; b) to assess whether the external environment and actors within it have changed; and c) to identify the scope conditions under which such change is likely. Chapter 10, which contrasts the use of conventional foreign policy and structural foreign policy in inter-regional cooperation, is a step in this direction. Overall, however, Stephan Keukeleire and Jennifer MacNaughtan neither equip us with sufficient analytical tools, nor do they give us a systematic empirical account of how the EU identifies its objectives of structural influence, how its policies correspond to these objectives, and how structures world-wide have (or have not) changed in response to Europe’s policy intervention. As it stands, The Foreign Policy of the European Union convinces as a rich, informative and in-depth account of EU foreign policy across its thematic board; yet it will disappoint those readers who do, indeed, expect a systematic reappraisal of this foreign policy as “structural.” Christine Reh‡ REFERENCES Bretherton, C. and Vogler, J. The European Union as a Global Actor. Abingdon: Routledge, 2006. Howorth, J. Security and Defence Policy in the European Union. Houndmills: Palgrave, 2007. )))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))) 20 Ibid., p. 19. ‡ Lecturer in European Politics in the Department of Political Science at the School of Public Policy, University College London. !"#$%"&#!'"&()*+,(!-)*'(!-.)%$/!$0))))))1))))/'(2)34)"'2)5))1)))'-#',$%))6778)) 87) ) ) Keukeleire, S. and MacNaughtan, J. The Foreign Policy of the European Union. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. Nuttall, S. European Foreign Policy, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. Smith, K.E. European Union Foreign Policy in a Changing World. Cambridge: Polity, 2008. Smith, M. E. Europe’s Foreign and Security Policy: The Institutionalization of Cooperation Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. TWO BAILOUT PLANS FOR PLANET EARTH BOOK REVIEW Common Wealth: Economics for a Crowded Planet. By Jeffrey Sachs. London: Penguin, 2008. Pp. xi+386. £9.99 (paper); ISBN-978: 0141026152. Hot, Flat, and Crowded: Why The World Needs a Green Revolution and How it Can Renew Our Global Future. By Thomas Friedman. London: Allen Lane, Penguin Group, 2008. Pp. 444. £20 (hard); ISBN-978:1846141294. Jeffrey Sachs, the Director of the Earth Institute at Columbia University, is the world’s most active fire-fighting economist. Having, over the last twenty years, taken on the liberalization of planned economies in the former Soviet bloc as well as the stubborn problem of hyper-inflation in Latin America, Sachs has more recently, in The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time21, set his sights on designing multi-year, multinational, and multibillion dollar projects to eradicate extreme poverty, control malaria, and stimulate a four-fold increase agricultural productivity in Africa. His current work, Common Wealth: Economics for a Crowded Planet22, aims no lower; Sachs now has a plan and budget to simultaneously mitigate global climate change, control population growth, protect biodiversity, reduce extreme poverty, and forestall serious )))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))))) 21 22 Sachs, J. The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time (New York: Penguin, 2005). Sachs, J. Common Wealth: Economics for a Crowded Planet (London: Penguin, 2008).