Document 13546491

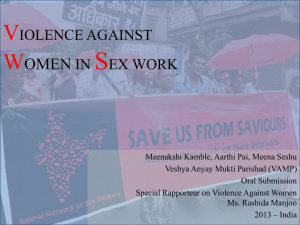

advertisement