T E C A

advertisement

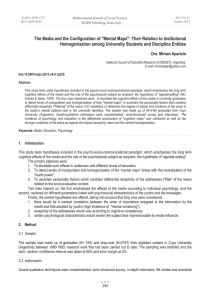

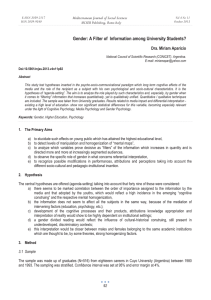

THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION AS AN AGENDASETTER: LESSONS FROM AND LIMITATIONS OF FORMAL ANALYSIS Daniela Ulicna‡ 1. INTRODUCTION The concept of agenda-setting is used in the literature to describe at least two different actions within the policy cycle, each taking place at a different stage. First, Kingdon discusses how an issue becomes a part of the political agenda, and he defines agenda-setting as a process through which an issue attracts the attention of policy-makers.1 Building upon the theory of “garbage cans”,2 he developed concepts of “policy windows” – the opportunity to push a policy through — and “policy entrepreneurs” – active advocates of particular solutions who identify and take advantage of policy windows. While these conceptions will be only marginally used in this essay it is important to know that they are both applied analyse the decision-making in the EU.3 The second conception of agenda-setting is inspired by the principal-agent framework where an agent, due to inequality of information, has (to a certain extent) the power to set the agenda for the principal. Rational-choice analysts ‡ M.Sc. candidate, School of Public Policy, University College London (expected November 2005); Contact with questions/comments: ulicnadan@yahoo.com. 1 J. Kingdon, Agendas, alternatives and public policies (New York: HarperCollins College Publishers, 1995). 2 M. Cohen, J. March, and J. Olsen., “A garbage can model of organizational choice,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 17 (March 1972), pp. 1-25. 3 See, for example, B. Wendon, “The Commission as image-venue entrepreneur in EU social policy,” European Journal of Public Policy 5, no. 2 (1998), pp. 339-353. See also L. Cram, Policy-making in the European Union: conceptual lenses and the integration process (London: Routledge, 1999). INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW, vol. I, no. 1 (September 2005): 121-132. [ISSN 1748-5207] © 2005 by The School of Public Policy, University College London, London, United Kingdom. All rights reserved. 121 122 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW conceptualise this agenda-setting power of the agent as the capacity to 1) choose from a set of alternatives acceptable to the principal the one that is the closest to the agent’s preferences and 2) to formulate this alternative into a particular piece of legislation upon which the principal decides.4 Tsebelis understands the agenda-setting power as the ability to formulate the legislation, to choose one particular alternative among other acceptable solutions, and to put it forward, in opposition to the veto-power (the capacity to reject the legislation).5 This conception is clearly different from the one held by Kingdon, who considers that this specification and the choice of policy alternatives is a different process from agenda-setting. Pollack remarks this variance in the use of the concept and uses the term “informal agenda-setting” for the definition used by Kingdon and his successors and “formal agendasetting” for the rational-choice understanding of the process.6 Even though the European Commission is mainly understood as the executive body of the EU, it also has the legislative power to initiate legislation. For a great part of EU policies the Commission even has the exclusive right to initiate the legislation. The Council shares this right with the Commission for policies included in the second and third pillar.7 Therefore, the Commission appears to be the major formal agenda-setter in the EU. Section 2 of this essay will analyse under what conditions the Commission can exercise its agenda-setting powers as it is understood by the rational choice approach. We will see that the literature concerned with the Commission’s formal agenda-setting is mostly based on the analysis of formal rules during the legislation process and the position of different actors in decision-making. We will examine the bases upon which a number of authors claim that the Commission can be a powerful agenda-setter. If their claim can be shown justified, it would constitute an argument in favour of a supra-nationalist interpretation of EU integration. Section 3 will examine the limits of this analysis, illustrated both by instances where the Commission failed to use its agenda-setting power and by those cases where it succeeded due to its informal agenda-setting. With reference to the principal-agent framework, it will be shown that the success of the Commission’s agenda-setting power depends on the willingness of the principal, the Council, and therefore the member states. 4 B. Tsebelis and G. Garrett, “Legislative politics in the European Union,” European Union Politics 1, no. 1 (2000), pp. 9-36; C. Crombez, B. Steunenberg, and R. Corbett, “Understanding the EU legislative process,” European Union Politics 1, no. 3 (2000), pp. 363-381. 5 Tsebelis and Garrett, “Legislative politics.” 6 M.A. Pollack, “Delegation, Agency and Agenda-setting in the European Community.” International Organization 51, no. 1 (1997), pp. 99-134. M.A. Pollack, The engines of European Integration: Delegation, Agency and Agenda-setting in the EU (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003). 7 See S. Hix,The political system of the European Union (New York: Pelgrave, 1999), Appendix, pp. 366-375. VOL. I, 2. NO. 1 — SEPTEMBER 2005 RATIONAL-CHOICE ANALYSIS OF THE AGENDA-SETTER 123 EU COMMISSION AS A FORMAL The major actors in the legislative process of the EU are the Commission, the Council of Ministers and the European Parliament (EP). The Commission, as it was already said, brings proposals of laws. Its agenda-setting power consists in the possibility to choose among different acceptable alternatives (i.e. those that would pass through the vote in the Council) the one that is closest to its ideal policy. The Council is a decisive actor in the adoption of every piece of legislation. Under certain circumstances, the Council can amend the legislation and it has the power to veto every piece of legislation. The impact of the EP varies according to the procedure under which the particular piece of legislation is adopted. For some types of legislation, the EP is not at all involved in the adoption process: for instance, it can delay legislation under the consultation procedure. Under the co-decision procedure, by contrast, it can also veto legislation and have a significant power to shape it by amendments.8 While in the former case, the Commission, as an agenda-setter, has to consider only the preferences of the Council and make a proposal that is acceptable by the Council, in the latter case (i.e. co-decision procedure) the Commission has to take into account the preferences of the EP as well. This increases the number of actors who can modify the original Commission’s proposal and potentially push the proposal further from the Commission’s ideal position. Thus, the agenda-setting power of the Commission is lesser under the codecision than under the two other procedures.9 Another important factor that influences the agenda-setting power of the Commission is the decision rules by which the legislation is adopted and amended.10 The agenda-setting power is important if it is easier for the decision-makers to adopt the legislation than to amend it. Under the consultation procedure, where there is only one reading, the Council can only amend the proposal by unanimity, while for some types of legislation it can adopt it by Qualified Majority (QMV). Therefore it is easier to adopt the legislation than to modify it. The Commission has significant discretion if the legislation is adopted by QMV. In that case the proposal has to satisfy the To see which type of law is adopted by which procedure see Hix, The political system, pp. 64-65. 9 G. Tsebelis, “The power of the European Parliament as a conditional agenda-setter” in The American Political Science Review 88, no. 1 (1994), pp. 128-142; C. Crombez, “The Treaty of Amsterdam and the co-decision procedure,” in The rules of integration: institutionalist approaches to the study of Europe, eds. G. Schneider, and M. Aspinwall (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001). 8 10 Pollack, “Delegation.” 124 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW median veto-players; therefore, the Commission can put forward an alternative closer to its ideal point, while if the Council is to amend the proposal, the amendment needs the support of all the actors, including the extreme veto-player closest to the Commission’s position and likely to support the initial Commission’s proposal. In a case where the decision rule requires a piece of legislation to be adopted unanimously, the Commission’s agendasetting power is weaker because the proposal has to satisfy the extreme vetoplayer (see Figure 1) and the same condition applies for the amendment put forward by the Council. It is equally difficult to adopt and to amend a proposal. Therefore according to the study of these rules, the Commission’s formal agenda-setting power should be greatest in cases of legislation adopted by QMV, under the consultation procedure, or without the involvement of the EP. Important issues fall into this category, such as the Common Agricultural Policy, some provisions concerning the Single Market (ex. liberalization of services) or Competition policy (e.g.. state aid). Figure 1 XL & XR – veto players in unanimity vote XQ & XQ* - veto players in QMV vote Source: Schulz, H.& Konig, T. (2000) “Institutional reform and decision-making efficiency in the European Union” in American Journal of Political Science 44(4); p. 657. Note: It is assumed that the position of the Commission is at the side of “more integration” further than the most integrationist member state. As was said previously, the Commission’s agenda-setting power is less under the co-decision procedure. The co-decision procedure, as it is functioning now (co-decision II), was introduced in the Treaty of Amsterdam. It was preceded by the co-decision I (Maastricht Treaty) and even before by the cooperation procedure (Single European Act). While the involvement of the EP was progressively becoming more important, several authors agree that the formal agenda-setting power of the Commission has progressively VOL. I, NO. 1 — SEPTEMBER 2005 125 decreased with the institution of each of these three procedures.11 However, there remains debate about to what extent is it decreasing. Crombez, for instance, claims that the Commission’s proposals done after the second reading have become irrelevant in the co-decision procedure: either the “joint text” is adopted (the result of conciliation between the Council and the EP) or the status quo remains.12 Even though the Commission issues its opinion, that either rejects or adopts the EP amendments, in the second reading, this opinion is not binding. On the other hand, Burns confirms that even though the Commission’s power is weakened it can still set the agenda if certain conditions are satisfied.13 Among the three conditions she formulates, the first is that “the Commission must share preferences with the majority of both the Council and the EP, or with a minority of the Council and the majority of the EP.”14 One might object, of course, that it is not clear what the Commission’s advantage would be if it shared the preferences of the majority in both the Council and the EP. The rational-choice models are all based on the assumption that the three actors have different preferences (König and Pöter 2001). If all three actors share the same preferences, there is no conflict, and therefore no advantage in setting the agenda. Furthermore, it is even less clear how the preferences shared by the Commission, the majority of the EP and only a minority in the Council could manage to pass through the legislative process. Since if the Council does not adopt the joint text by QMV the legislation fails. Similar objections could be done to the second condition concerning the levels of “impatience”, if all three actors share the same level of “impatience” none of them can take advantage of it. Among the three conditions she lists only the third one concerning the lower likelihood of Commission’s success when it has a bad relationship with the EP rapporteur holds. Another reason that makes the Burn’s article less convincing is the fact that it is based on only one case study (food labelling). As was noted earlier, rational-choice approaches to agenda-setting is mainly focused on the analysis of rules. Authors provide few tests and case studies that would support their results. Among the few authors providing a test is Tsebelis, who concludes that the Commission’s behaviour (refusal or adoption of EP’s amendments) predicts the refusal or adoption of 70% of the 11 Tsebelis, “The power”; C. Crombez, “Legislative procedures in the European Community,” British Journal of Political Science 26, no. 2 (1996), pp. 199-228; C. Crombez, “The Treaty”; C. Burns, “Co-decision and the European Commission: a study of declining influence?” Journal of European Public Policy 11, no. 1 (2004), pp. 1-18. For the details of the three procedures and their differences, see Hix, The political system, pp. 86-87. 12 C. Crombez, “The Treaty.” While in the co-decision I it was the Common Position adopted by the council on the basis of Commission’s proposal that was adopted in case there is no agreement about the joint text. 13 Burns, “Co-decision.” 14 Ibid., p. 15. 126 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW legislation under the co-decision procedure, while it was a better predictor (85%) under the cooperation procedure.15 These results show that in fact the Commission’s influence was weakened, but not annihilated (as Crombez suggests), since it well predicts for nearly three-fourths of the legislation, by the passage from cooperation to co-decision. Despite the disagreement among authors using different models for the analysis of the EU decision-making,16 the rational choice literature comes to the conclusion that the Commission did have a significant formal agendasetting power in the EU decision-making process but that this has weakened over time. The Commission’s agenda-setting power should be greatest in the case of legislation adopted by QMV in the Council and through procedures that do not include the EP. In that case, the Commission should be able to impose legislation against a minority in the Council. It appears also that while the EP is pushing for more involvement in the legislative process and since the co-decision procedure is becoming more used, the formal agenda-setting power of the Commission might well progressively decrease.17 However even though there is a substantial literature discussing these various models of legislative process there is less evidence to support their results.18 In the next part we will consider concrete examples of agenda-setting in the EU and we will examine the objections addressed to the rational-choice literature on this subject. 3. ILLUSTRATIONS OF COMMISSION’S ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND THE LIMITS OF FORMAL RULES ANALYSIS. The first objection made to the previously discussed literature has already been depicted: a lack of empirical evidence.19 The second objection is that when discussing only the formal decision rules authors do not give account of the whole decision-making process, they neglect the informal rules that are significant in the EU as in other polities (Schmidt 2001). According to the results of the rational-choice theory, the Commission has a significant number 15 G. Tsebelis, C. C.B. Jensen, A., Kalandrakis, and A. Keppel, “Legislative procedures in the European Union : An empirical analysis,” British Journal of Political Science 31, no. 4 (2001), p. 595. 16 Crombez et al., “Understanding.” P. Moser, “The European parliament as a conditional agenda-setter: What are the conditions? Critique of Tsebelis,” American Political Science Review 90, no. 4 (1996), pp. 834-838. Tsebelis, “The power.” 17 Crombez, “Legislative procedures.” 18 T. König and M. Pöter, “Examining the EU legislative process: the relative importance of agenda and veto power,” European Union Politics 2, no. 3, pp. 329-351; S.K. Schmidt, “Only an agenda-setter? The European Commission’s Power over the Council of Ministers,” European Union Politics 1, no. 1 (2000), pp. 37-61; Crombez, Steunenberg and Corbett, “Understanding.” 19 S.K. Schmidt, “A constrained Comission: informal practices of agenda-setting in the Council,” in Schneider and Aspinwall, The rules. Pollack, “Delegation.” VOL. I, NO. 1 — SEPTEMBER 2005 127 of opportunities to push forward its preferred policies. This literature also understands the Commission as being in conflict with the member states, since it is assumed to hold a more integrationist position. According to the principal-agent framework the Commission is seeking for more competences for itself and therefore more integration.20 However, it will be shown here that these assumptions have to be nuanced— since the Commission is an efficient entrepreneur mostly in cases where it has the support of the Council—and that it is unable to impose its view through an opened conflict with member states. This argument is also supported by König and Pöter’s analysis, in which they conclude that the rational-choice models previously discussed overrate the agenda-setting power of supranational institutions since it is not a very good predictor of policy change.21 As was mentioned previously, among the areas where the Commission should have the best chances to exploit its agenda-setting power are the CAP and the liberalisation of services. Pollack’s analysis an example of the first,22 studying MacSharry’s CAP reform, in which he finds that even though the Commission was activist during the negotiations it was constrained by the member states and the use of consensus decision-making.23 Similar analysis is provided by Schmidt who provides counter-examples of what would be expected by the formal agenda-setting literature.24 She analyses five examples of legislation where the Commission should have had (according to the rational-choice models) taken advantage of its agenda-setting power and it did not. One of these examples is the liberalisation of electricity services. Policies concerning the liberalisation of services belong to the category of policies decided by QMV under the consultation procedure.25 In the case of electricity services the Commission’s proposal faced severe opposition of France and mild opposition of Italy and Greece. However, as shown in Figure 2,the Commission’s proposal could have obtained the majority in the Council at the expense of a great disproval of the French government. Rather than this, the Commission eventually accepted several changes to its proposal under the pressure of various Council presidencies and the version finally adopted satisfied even the most extreme actor, France. Schmidt explains this outcome by the informal rule of consensus in the Council.26 Another author who arrived at similar findings is Thatcher in his analysis of telecommunication’s Pollack, The engines. König and Pöter, “Examining.” 22 Pollack, The engines. 23 Ibid., p. 322. 24 Schmidt, “A constrained.” 25 Hix, The political. 26 Pollack underlines the same obstacle to Commission’s agenda-setting in his analysis of the Working Time directive. Pollack, The engines. 20 21 128 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW liberalisation.27 All these examples show that in cases where the Commission has the possibility to exploit its agenda-setting power but risks a major conflict with one or more governments, a consensual solution prevails. Figure 2. Preference Distribution in the Electricity case Source : Schmidt, S.K. (2001); p. 134 However this does not mean that the Commission never acts as a policy entrepreneur. In cases concerning less politically sensitive issues, the Commission may manage to push through policies in fields where it is supposed to be disadvantaged according to the rational-choice analysis of decision rules. The Social policy does not belong among the policies where the Commission has the greatest chances to exploit its agenda-setting power (decisions are taken at unanimity in the Council). Despite this initial disadvantage, Pollack and Hafner-Burton show how the Commission did significantly influence the legislation in this area.28 The authors analyse gender mainstreaming policy promoted by the Commission across various other policy fields. They claim that the condition for the Commission’s success in this case was careful and strategic formulation of its proposals. They show how the different “gender mainstreaming officials” in different DGs managed to introduce this new policy into areas such as Structural Funds, Employment, Development, Research and Competition, successfully producing regulations, guidelines and programmes in the first four policy fields. In all the cases the M. Thatcher, “The Comission and national Governments as partners: EC regulatory expansion in telecommunications 1979-2000,” European Journal of Political Science 8, no. 4 (2001), pp. 558-584. 28 M.A. Pollack and E. Hafner-Burton, “Mainstreaming gender in the European Union” European Journal of Public Policy 7, no. 3 (2000), pp. 432-456. 27 VOL. I, NO. 1 — SEPTEMBER 2005 129 gender mainstreaming was introduced into existing policy frames of the five DGs “emphasising efficiency (as opposed to equality)” which made Commission’s proposals politically more acceptable in the Council.29 It is also important to mention that originally only a minority of member states (mainly Scandinavian countries—two of which were new members at the time these policies started) had a substantive experience with gender-equality policies. Therefore, we could expect the majority in the Council to be hostile to this type of policies. When we join to this the fact that the Council is usually reticent to regulate social policies at the EU level, we can consider that the gender mainstreaming is a good example of Commission’s leadership and its informal agenda-setting power. The last was reflected in the fact that the Commission brought the gender issue to the EU agenda and developed a new EU policy—gender mainstreaming— with an initial support of only a minority of member states. On the other hand, this case can not be taken as an example of Commission’s formal agenda-setting power since the decisions in the Council were taken at unanimity and the Commission was not taking advantage of the formal decision rules. What we observe, as Cram underlines, is rather the ability developed by DG V (Employment, Social affairs, etc.) to “package issues in the form likely to engender least opposition in the Council.”30 4. CONCLUSION This analysis of Commission’s agenda-setting powers reveals that even though theoretically the Commission could be dictating the agenda under some conditions, there is little evidence of this really happening. The Commission does in fact behave as an agent searching to maximise its preferences, but the agenda-setting power alone does not give it enough possibilities to overrule the Council. It appears also that the analysis of formal rules of the legislative process does not explain why the Commission would not succeed in cases such as Electricity liberalisation (discussed above) or the Working Time Directive.31 In order to understand the EU decision-making process other perspectives have to be added, including the study of informal rules. An issue which was not discussed in this essay, but was touched on in the introduction, is the rise of issues on the EU agenda rather than their formulation. The case of gender mainstreaming, exposed above, could raise the question of whether if the Commission is not an agenda-setter in a sense of “formulating its preferred policies into legislation,” it could be an agenda-setter in a sense as Kingdon understands it, bringing in new issues and acting as a policy entrepreneur. However, such study would involve analysis of other Ibid. Cram, Policy making, p.162 31 Pollack, The engines. 29 30 130 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW actors, such as interest groups, and would require more than the space available here. VOL. I, NO. 1 — SEPTEMBER 2005 131 REFERENCES Burns, C. “Co-decision and the European Commission: a study of declining influence?” Journal of European Public Policy 11, no. 1 (2004): pp. 1-18. Cohen, M., March, J. and Olsen, J. “A garbage can model of organizational choice.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 17 (March 1972): pp. 1-25. Cram, L. Policy-making in the European Union: conceptual lenses and the integration process. London: Routledge, 1999. Crombez, C. “Legislative procedures in the European Community.” British Journal of Political Science 26, no. 2 (1996), pp. 199-228. ———. “The Treaty of Amsterdam and the co-decision procedure.” In The rules of integration: institutionalist approaches to the study of Europe, eds. G. Schneider, and M. Aspinwall (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001). Crombez, C., Steunenberg, B. and Corbett, R. “Understanding the EU legislative process.” European Union Politics 1, no. 3 (2000): pp. 363-381. Hix, S. The political system of the European Union. New York: Pelgrave, 1999. Kingdon, J. Agendas, alternatives and public policies. New York: HarperCollins College Publishers, 1995. König, T. and Pöter, M. “Examining the EU legislative process: the relative importance of agenda and veto power.” European Union Politics 2, no. 3 (2001): pp. 329-351. Moser, P. “The European parliament as a conditional agenda-setter: What are the conditions? Critique of Tsebelis,” American Political Science Review 90, no. 4 (1996): pp. 834-838. Pollack, M.A. “Delegation, Agency and Agenda-setting in the European Community.” International Organization 51, no. 1 (1997): pp. 99-134. ———. The engines of European Integration: Delegation, Agency and Agendasetting in the EU Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. Pollack, M.A. and E. Hafner-Burton. “Mainstreaming gender in the European Union.” European Journal of Public Policy 7, no. 3 (2000), pp. 432-456. Schmidt, S.K. “A constrained Commission: informal practices of agendasetting in the Council,” In The rules of integration: institutionalist approaches to the study of Europe, eds. G. Schneider, and M. Aspinwall (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001). ———. “Only an agenda-setter? The European Commission’s Power over the Council of Minister.” European Union Politics 1, no. 1 (2000), pp. 37-61 Thatcher, M. “The Comission and national Governments as partners: EC regulatory expansion in telecommunications 1979-2000.” European Journal of Political Science 8, no. 4 (2001): pp. 558-584. Tsebelis, B. and Garrett, G. “Legislative politics in the European Union,” European Union Politics 1, no. 1 (2000): pp. 9-36. 132 INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW Tsebelis, G. “The power of the European Parliament as a conditional agendasetter.” American Political Science Review 88, no. 1 (1994): pp. 128-142. Tsebelis, G., Jensen, C.B., Kalandrakis, A. and Keppel, A. “Legislative procedures in the European Union: An empirical analysis.” British Journal of Political Science 31, no. 4 (2001): pp. 573-579. Wendon, B. “The Commission as image-venue entrepreneur in EU social policy.” European Journal of Public Policy 5, no. 2 (1998): pp. 339-353. INTERNATIONAL PUBLIC POLICY REVIEW, vol. I, no. 1 (September 2005): Error! Bookmark not defined.-Error! Bookmark not defined.. [ISSN 1748-5207] © 2005 by The School of Public Policy, University College London, London, United Kingdom. All rights reserved. 133