Progress Against the Law: Fan Distribution, Copyright, and the Abstract

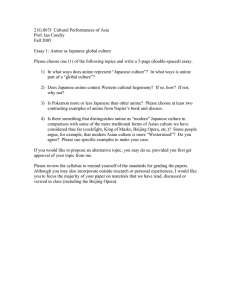

advertisement