The eternal return : The Shipping News and the consideration... by Melissa Anna Jaten

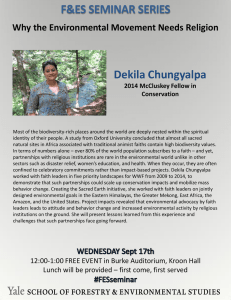

advertisement